Emily Sun begins her book Succeeding King Lear with words from the philosopher of authoritarianism, Hannah Arendt: “no man can be sovereign because not one man, but men, inhabit the earth.” King Lear is a play of transition, of a dying order given way to a new one. Its monarch, faced with old age and a treacherously changing new world, can rest no longer on a singular, universal sovereignty, and in the slow abdication of his throne Lear is mistaken that he alone can rule among men — or women.

Arendt had not anticipated Glenda Jackson.

I’ll put it another way. At the very end of the play, King Lear and all three of his daughters now dead, the survivor-king Edgar proclaims: “The weight of this sad time we must obey / Speak what we feel, not what we ought to say. / The oldest hath borne most; we that are young / Shall never see so much, nor live so long.”

The quatrain is not simply Edgar’s question of what it has been to see King Lear, but what it has meant to witness Shakespeare’s King Lear. It is a delineation of old to new that recognizes squarely the role of the spectator in that transition. The task of living after having seen King Lear is to make a new beginning, not the same mistakes of that aged king.

But in a new production of King Lear which opened on Broadway this month, directed by Sam Gold and carried by Glenda Jackson, King Lear is itself a text nightly in the process of glorious renegotiation. Glenda Jackson, who these days is heralded as the greatest living actress and whose guttural, contralto voice was once called a great instrument of the theatre, does not merely perform the monarch with terrifying precision. She has changed the performance of King Lear in a fundamental way, communed almost divinely with its author to excavate a tragic king with more devastating definition than ever before.

That’s a bold claim, and it’s not an exaggeration. King Lear was first performed in 1606, written as Shakespeare’s pivot from the history play to the tragedy, his entry into the exploration of humanity. It stands as a colossus in the Shakespearean canon and is the greatest effort of his imagination. King Lear encompasses a whole society, from king to beggar, and registers suffering and torture, authoritarianism and ferocity to an epic and mythical degree.

For sometime the play was unperformed, thought to be unactable, either because of its unbending cruelty or its mammoth scope, too huge and too insufferable for the stage. It was rewritten because it was thought to be too tragic. In 1681, Nahum Tate rewrote the tragedy with a happy ending, the adaptation entirely replacing Shakespeare’s version on the English stage until 1838. Only in the years after the Second World War, the world perhaps changed amid the torture and genocide wrought by the 20th century, has the play returned to the stage as a masterpiece.

Still, productions of Lear have largely aligned themselves along two interpretations, grappling to stage the utter contradiction of a king who must either slough off the monarchical robes of power to become an aged man and father, disarmed and then restored to peace, or grip his subjects with an unnervingly mad, divine and ancient fist even as his body decays into death. Traditionally, the play has emphasized Lear as the imperious monarch, the frightening ruler who even in dementia can not shed the garments of absolute power. Modern stagings, exemplified by the 1990 National Theatre production, which pushed Brian Cox as King Lear onto the stage in a wheelchair, have depicted a humbled King, grasping at his faded and dying authority while those around him pervert a kingdom he once ruled with grace.

Glenda Jackson has changed productions of this play because she can, with rapturous, captivating dexterity, do both. Her King Lear is both crushingly elegiac and irreverently horrid, spine-chillingly terrifying and, somehow, grievously somber.

In the opening scene, as Lear divides his kingdom among his daughters — taking the extraordinary step of doing what only he has the power to do: end his own sovereignty — and is met with the insubordination of his favorite, Cordelia, thrusting the play into the uncertain realm of theater, Lear declares: “’tis our fast intent/ To shake all cares and business from our age,/ Conferring them on younger strengths, while we/ Unburdened crawl toward death.” But when Jackson says the line she rolls the ‘r’ in crawl — more like “crrrrrrawl toward death” — as if she’s mocking the inevitability of it all, the source of such flippancy as much absolute authority as it is fear.

Hair raised, the audience laughs — but it’s in the small details of line readings like this one where Jackson’s brilliance lies, creeping and unexpected. That “crrrrrawl” is irony; that’s why it reads as humorous. Here, Jackson’s Lear acknowledges the natural, impending descent toward death, the necessary abdication of responsibility and dominion; in other words, he is humble. But her Lear does not humble himself without a firm, controlling hand, able to beguile both language and audience at whim — a masterful manipulator and a tyrant with effortless authority. In that moment her Lear crosses over into what Jacques Lacan would call the exceptional zone between two deaths — “l’entre deux-morts — between the insecurity of his own abdication and death itself, and stays there, precariously, until he breathes his last. We ache for Lear, lament with him and, at the same time, recoil in fright. That, in no uncertain terms, is acting at its most thrilling.

In the storm scene, cast out by his daughters and maddened as the thunder and wind rage, Jackson’s Lear is bloodcurdling. Commanding to “Crack nature’s molds, all germens spill at once/ That make ingrateful man!” Jackson strikes immediate and unforgettable fear in her audience. And in his last moments, flitting with the dying hand of her Cordelia (Ruth Wilson), her Lear is sorrowfully tender, burdened, still, by the tragedy of his own authority.

If Glenda Jackson is the power and the glory, Ruth Wilson, who plays both Cordelia and the Fool, is the heart of this production. The decision to cast the same actress in these roles, both characters similar in their ability to confront father and master with defiance, is a rewarding one that, if only through the medium of a masterful actress, ties the audience closer to Cordelia, who spends most of the play offstage, her death now ever more powerful.

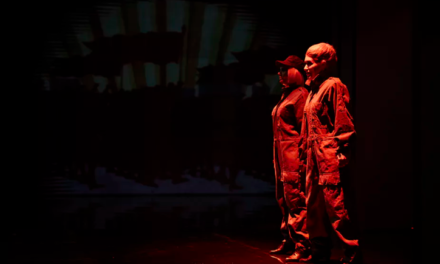

Ruth Wilson and the cast of King Lear. Courtesy of Brigitte Lacombe.

The Fool’s prophecy in Act 3 — that, when things will be what they are, our present country will fall to ruin — is among the most weighty, powerful moments in this play. As Wilson delivers the prophetic monologue, plainly and grimly, she removes her wig as if to step out of character and lifts her pants to reveal her socks, colored with the stars and stripes. It’s the closest this play strides toward political commentary. To go any further would be to sully King Lear with opportunism — surely the mythical highs and lows of this story supersede any momentary, topical politics. But Wilson is graceful and foreboding, outside of Jackson the most comfortable actor in this production, attentive and careful, though imaginative within Shakespearean prose. As Gloucester, Jayne Houdyshell deserves similar praise, a first-rate Shakespearean character, and a grounding, familiar force at the Cort Theatre.

All of this does not absolve the rest of Sam Gold’s production, which scrambles to wrap Jackson in a design that matches her own ability.

The stage of the Cort Theatre is encased in gold (scenic design by Miriam Buether), its ceiling laminated with a shiny, metallic glaze that directly references the gilded, Aurelian aesthetic popularized by Donald Trump, if not for the real gold leaf which flakes off the textured walls. Its a visual reference that too attempts to tie the ancient, pre-historic realm of King Lear to some modern political setting, but the gesture, however evocative, seems out of a place in a production that’s put its weight on Glenda Jackson’s shoulders, who’d dare not steep her King Lear, or William Shakespeare, in the lowly waters of easy political narrative. There are other elements of the scenic design, like a porcelain bulldog and lion next to Lear’s throne, which I wish I could interpret for you but which make little visual sense.

Similar issues abound with the jagged, dramatic score written for string quartet that Phillip Glass has written to accompany this production. It’s clear that Gold and Glass have striven to include the orchestration gingerly so as not to impede the play, placing the quartet in the back corner of the cavernous stage, as if they’d been hired to unobtrusively accompany some banquet gala. Yet, as a result, the music seems like an afterthought added to throw as much alluring artistry into this production as possible. While the music is harrowing and foreboding, its chromatic tension mirroring Lear’s mad descent into dementia, the string quartet, equipped with no percussion (although, curiously, advertisements for the play disseminated across social media do feature music with percussion), fails to meet Jackson’s dramatic height.

That seems to be a theme. Ann Roth’s costuming shines greatest in the regal dresses of Lear’s three daughters, opulent and graceful, and Glenda Jackson, who herself is no stranger to wearing suits on the red carpet, seems a natural fit for the loose-fitting tux she wears as Lear. But the anachronistic costuming, nearly cliche with contemporary productions of Shakespeare seeking to catapult their staging into some ambiguous modernity, adorns with no clear dramatic or artistic reference.

There’s one thing I’ve left untouched so far — and that’s of course that there’s a woman, an 82-year-old woman, in fact, playing King Lear on Broadway. And I’ve left it unsaid merely because, if you take anything away from this momentous showing of King Lear if anything hangs in your mind as you exit the Cort Theatre’s doors, it’s that Jackson’s age and gender seem nearly immaterial to this production. She is simply too great an actress, her Lear too profoundly devastating, to muddy with perseverations of age and gender. Like King Lear, Glenda Jackson is in some way implausibly, dramatically capacious, striding improbable and at times contradictory heights, allegorical in proportion and design. Glenda Jackson’s Lear defies gender, in her age and experience the shackles of the feminine or masculine assignment are unbound, just as Lear is himself unbound from the signifying robes of regal authority. Her Lear is both aged and ageless; whatever senescence she wears clothes a timeless and unforgettable power.

“Who is it that can tell me what I am?” Lear asks his subjects. Glenda Jackson answers.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Michael Appler.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.