Jan Kott wrote that in Shakespeare’s Macbeth, history is shown as a nightmare, something that shocks and terrifies; that it is opaque like a nightmare. ” And, like in a nightmare, everyone gets bogged down in it.” In Warlikowski’s Macbeth, this nightmare seems to have no end. Nor a beginning.

1. Three scenes, three images, and situations.

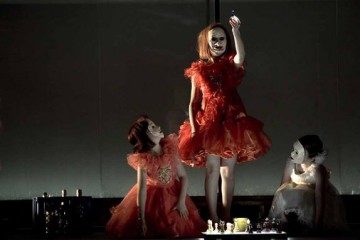

The first one. Macbeth (Scott Hendricks) and Banquo (Carlo Colombara), in combat trousers and white T-shirts, lie on the floor and play chess (we see the same an image of the chessboard, black-and-white and grainy, on a large screen above the stage). Behind them, a glazed-in room full of children. Children? Young girls in female dresses and wigs, in masks with strong make-up. Parading like in a red-light district, simpering in front of potential clients, put on display. During the same time, a choir of witches (standing in the audience balconies) sings, in three-part harmony, the prophecy of Macbeth and Banquo. The girls walking around the men, their shadows reflected on the right side. At some point, Macbeth runs up to the wall to touch a human contour. The shadow becomes pale.

Giuseppe Verdi Macbeth conductor Paul Daniel, director Krzysztof Warlikowski Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie in Brussels, premiere June 11, 201o

The second one. Following the murder of Duncan, towards the end of Act 1, a hypnotic, collective (Macbeth, Lady Macbeth – Iano Tamar, Banquo, Macduff – Andrew Richards, Malcolm – Benjamin Bernheim, the servants) song with choir resounds. We see the frozen faces in close-ups on huge plasma screens on the stage and above it. Eight small boys enter, in dark suits, carrying a coffin for the king. (I am reminded of how, following the Smolensk plane crash, children in one of Warsaw’s kindergartens were told to arrive dressed in black next day). Deeply moving.

And the third one. Beginning of Act 4. A choral lamentation by the refugees (“Patria Opressa!… For all your children you have become a tomb!”). On the floor, several children in navy-blue costumes, blowing soap bubbles. A woman enters, also in navy blue, with a bottle of milk and several glasses on a tray. Still playing, the kids come up to her and drink the milk. They return to their places. She drinks too. A moment later, each of them, without a sound, as if imperceptibly, slumps to the floor. Dead. Like a nightmarish recollection of the wives and children of Nazi commanders. The servants carry out the small bodies one by one. Macduff sings “O figli miei!” Dark as despair.

2. Giuseppe Verdi’s Macbeth premiered in Florence on March 14, 1847 (eighteen years later, a French-language version was created, with some revisions and changes). The composer was thirty-three years old then, and still before his most important operas: Rigoletto (1851), Traviata(1853), Un Ballo In Maschera (1859), Aida (1867), Otello (1887), Falstaff (1893).

The work was not an instant success though: the audience missed a romantic conflict or great tenor arias (the main character is a baritone). Still, the reception (both in Florence as well as later in Paris) was sympathetic. The composer himself ranked Macbeth very highly among his works.

Photo: Bernd Uhlig

And it is no wonder. It is an unusual work; sort of uneven, fragmented, harsh, wild. From the very beginning, from the first zigzagging melody opening the overture, the angry signal of the trumpets and trombones, this nervousness intrigues and disturbs, fascinates. At first, the scenes are long and complex, to then, as the plot develops, become shorter, condensed (Act 3 has only one scene). The mood changes, although dense gloom, greyness, prevails (grey is the dominant color in Małgorzata Szczęśniak’s scenography, the color of all the walls). A deaf darkness.

3. Verdi’s Macbeth is the second opera staged by Krzysztof Warlikowski in Brussels, following Cherubini’s Medea (2008). It is also the second Verdi opera on his record, following Don Carlos ten years ago in Warsaw. Nor should we forget that in 2004, in Hanover, Warlikowski staged the Macbeth by Shakespeare.

In that show, the Polish director used fragments of films, such as Roberto Rossellini’s Germany Year Zero, Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard, or Fritz Lang’s Nibelungen. It is a similar case in the Brussels Macbeth, whether in terms of inspiration or on stage. The show’s program is illustrated with images from movies such as Olivier Stone’s Platoon, Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker, or Liliana Cavani’s Night Porter; the dramaturge, Christian Longchamp, mentions also Michael Cimino’s Deer Hunter, Stone’s Born On The 4th Of July, or Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket.

In the onstage projections, we see mainly fragments of Nicolas Ray’s 1948 They Live By Night, a black-and-white overture for Bonnie And Clyde. The main character, Bowie (Farley Granger), escapes from jail, where he had been put after being wrongly sentenced for murder; he wants to start a new life with Keechie, (Cathy O’Donnell), a petrol station owner’s daughter he has met by chance. Alas, the past returns–the two thieves he had escaped with betraying him. Bowie dies and Keechie, pregnant, has to manage by herself.

Photo: Bernd Uhlig

The program features a black-and-white still image from the movie. A man and a woman lying on the floor, close to each other, like intimate strangers. Worried. Her gaze seems to be dreaming of a quiet future, his returns to the bad past. There is a darkness in them (a black background like an abyss), an impossibility, lack of faith. As if they sensed that their love would not have a happy ending. On stage, at the very beginning of the show, we watch the film’s opening credits, and then looped fragments several times during the first part (that is, before the interval, in Acts 1 and 2) on several plasma screens on stage and above its window.

The movie, as well as the other tropes scattered throughout the show (e.g. a US soldier’s letter from Vietnam featured in the program or the prose by Jonathan Littell), are not just a gimmick or silence-filling gadget. They serve as means of expanding the battlefield, widening the perspective, snatching the opera out of a solely musical context. I bridled at it in Szymanowski’s King Roger (Opera de Paris, June 2009), but here it is right to the point.

Images from American movies about Vietnam (Macbeth and Banquo wear khaki uniforms) open the Shakespeare story to another time – the modern-era post-war trauma and infection with death, the impossibility of living outside the battlefield. (In fact, the bald-headed Macbeth disturbingly resembles Marlon Brando’s Kurtz in Apocalypse Now). The context of the Nicholas Ray film is clear: however as hard as Mr. and Mrs. Macbeth try, they will not escape their fate. They will not escape the madness of darkness and death.

4. The space is basically one, common for the staging as a whole. A wooden parquet floor, several large grey walls with huge windows. Like a waiting room or community hall, a field hospital; a place of shelter and isolation. The side walls do not run evenly and do not close off the backstage. On both sides similarly, almost symmetrically: a large block, a break (for the lights or for the singers to pass), another wall with two large sectioned windows; low by the floor, old-style radiators, long heating pipes at the front and back. On the left, closer to the orchestra pit, a washbasin. The back wall divided into two parts: glass below (the girls in the first scene strolling behind it), a block of grey surface (often serving as a screen) above. Finally, large fans suspended from the ceiling, in various arrangements: usually one (in the center), sometimes two (symmetrically on the left and right), casting disturbing shadows on the walls and floor.

In fact, light is this show’s (silent) protagonist in itself. Felice Ross knows how to beguile, delude, hypnotize. Here, she uses various principles to help the space materialize. One of those are afterglows cast through the windows, never symmetrical (the shadows cast on the side walls are different, the colours too), another one are colors–suppressed, austere (cold white turning into grey, sometimes blue–as in the scene of Banquo’s murder, finally burning yellow in the scene of the children’s murder). The whole thing has a film-noir look, a special kind of black-white on a grey background. The logic underlying this solution virtually stings the eyes.

5. Jan Kott, quoted in the show’s program, wrote that in Shakespeare’s Macbeth, history is shown as a nightmare, something that shocks and terrifies; that it is opaque like a nightmare. “And, like in a nightmare, everyone gets bogged down in it.” In Warlikowski’s Macbeth, this nightmare seems to have no end. Nor a beginning.

Photo: Bernd Uhlig

During the overture, a small illuminated wall-curtain rises by a little more than a meter. On the floor, on the left, Lady Macbeth, with a small lamp pointed straight into her face. Macbeth besides her, shrunken, huddled, in paralysis. Following the famous sleepwalking madness scene in Act 4 (“Una macchia è qui tutora…”), Lady Macbeth, in a light-colored flower-patterned dress, in grey hair as if at least a dozen years have passed, lies down in the same position on the floor, in exactly the same spot.

In the final scene–the scene of Macbeth’s death (the show’s authors had chosen the opera’s second version, from 1865, but the scene in question comes from the original version)–we see Macbeth besides his wife who lies on the floor. A moment before, he had sat for a long time (e.g. during the children’s suicide scene) in a wheelchair, tended by a black carer-bodyguard in a white tuxedo. Now he lies on the floor as if paralyzed. Above him, in combat trousers and boots, his face smeared, Macduff, holding an ax wrapped in a dirty rag. He stands above Macbeth, ready to make the blow. Macbeth does not try to defend himself, almost stretches his neck out. The music stops, end of the show.

The nightmare becomes most pronounced in the final scene of Act 2, during the dinner party. A fully laid table, Macbeth in a black tailcoat, Lady Macbeth in a beautiful black dress, both in central places, surrounded by friends of the house, servants in navy-blue uniforms (the lower part of the stage is illuminated blue, the rest lost in greyness). On the table, among the plates, a revolving camera the source of the magnified black-and-white image projected on a wall-screen at the top of the stage. Large moving faces, unnatural, twisted, smiling, and pained. Macbeth keeps running away from the table, seeing the dead and murdered (Banquo!), talking to himself. He returns and wants to make a toast. His face is horrible, especially when the image from the camera is multiplied (the camera records not only Macbeth’s face but also its image projected on the wall). The whole harmonizes brilliantly with the madness of the music.

Photo: Bernd Uhlig

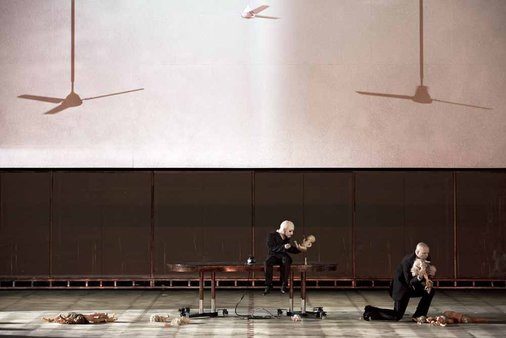

Act 3 begins with the second prophecy scene. At the same table, Macbeth meets the little girls–still in their white masks and wigs, but this time in light-colored children’s dresses. The girls hold dolls in their hands and begin to tear their limbs off, throwing them on the floor. When, a moment later, the witches show the king gallery to Macbeth, we see a row of eight school desks behind a glass wall. A boy in a mask resembling Banquo’s face at each one. Macbeth lies on the proscenium, singing, twisted in pain, in the hope that the nightmare will finally end. But its climax is only beginning. Macbeth collects the scattered doll limbs as if he wanted to put back together the world disintegrating around him. Only one boy in a Banquo mask remains on stage. (The program features a 1959 work by Ralph Eugene Meatard, showing a small boy in an oversize old man’s mask, sitting amid foliage by a shed-bunker, holding a small doll). He pricks needles into the naked doll, Macbeth’s body writhing in paroxysms of pain. But the voodoo fails to bring about the desired end. The nightmare continues.

6. The Macbeth at La Monnaie is phenomenal–in theatrical as well as musical terms. Paul Daniel, the British conductor, brilliantly combines the visionariness of Warlikowski’s staging with the nervousness of Verdi’s music. He clashes the extremity-thundering winds with the lyricism of the strings, raising the volume, intensifying rhythms, amplifying the contrasts. Off-stage music is heard from a recording, which only enhances the adaptation’s film feel.

Photo: Bernd Uhlig

The lead soloists–Scott Hendricks as Macbeth, Iano Tamar as Lady Macbeth, Carlo Colombara as Banquo, Benjamin Bernheim as Macduff–deliver superb performances. Each one of them belongs perfectly well in the world of contrasts and tensions created by Krzysztof Warlikowski and his team (Małgorzata Szczęśniak, Felice Ross, Denis Guéguin – video, Saar Magal – choreography), a world in which music, although it does not seem to be the most important thing, connects the distant and separate.

The show’s great hero – though absent from the stage – is the Brussels opera’s choir. Its compact, dry, sharp sound intensifies the sense that the singing, the music, surround us from all sides. That we are in a trap, a prison. Like Shakespeare’s and Verdi’s protagonists.

7. “There is destruction in Macbeth. Look at the Hollywood movies, the returns home from Vietnam. Those were mutilated people, without a will to fight, destructive, suicidal. When you return from war, you may think that you control your will, you fight for something, that it makes sense, but deep down in your subconsciousness, you no longer have the power to live a different, constructive life” Warlikowski told Piotr Gruszczyński in the book Szekspir I Uzurpator (Shakespeare And Usurper).

And also of the Hanover Macbeth: “My witches were war children, prostituted girls roaming the corpse-covered roads. It was something objective and subjective, which the soldiers returning from war could really happen upon…. The second encounter is more imaginary and experienced rather in the head of the upset Macbeth who thinks he has some power and that somewhere out there, there is a world that wants to tell him something, give him a hint. This is a kind of hallucination. And the first vision is perhaps a real meeting with real girls, make-up wearing, disturbing, perhaps war victims?”

Photo: Bernd Uhlig

It is a similar case in the Brussels Macbeth. But one scene–the murder of Duncan–changes the perspective somewhat. When talking with his wife, Macbeth washes himself in the sink; during the same time, four beds appear on stage–hospital beds, but double ones, very wide; besides them, plasma TV sets (showing looped fragments of They Live By Night). Arranged in a rectangle: Macbeth with his wife, Banquo at the back, the king’s two bodyguards on the right, and Duncan behind them. All in one room. Like patients of the same field hospital, like war veterans living in the same shelter.

The director’s words suggest that in Hanover, the girls-witches appeared hyenas, hunting on the warpaths. In Brussels, they are even more real, like the children of all those who live in this secluded world. Even more guilty, like pure evil. Towards the end of the show, the boy in the Banquo mask appears again, running around the room, finally pulling the mask off; he reveals his true, childish face as if he wanted to say that the other role has been fulfilled, completed.

In the finale, when Macduff stands with the ax above Macbeth, we watch the final projection. A figure in a desert, among dark lumps of earth and sand, amid rushing wind. Walking and shouting. (It is the silent finale of Pasolini’s Teorema, wherein the film Mozart’s Requiem resounds movingly). Like a freed soul. In Warlikowski’s Macbeth, the protagonists are stuck in a nightmare until the end. There will be no catharsis.

This post originally appeared on Biweekly.pl in July 2010 and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Tomasz Cyz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.