I’m an outsider everywhere. I was an outsider in my family. I was an outsider where I grew up. I’m an outsider in Austria. No sentiment though.

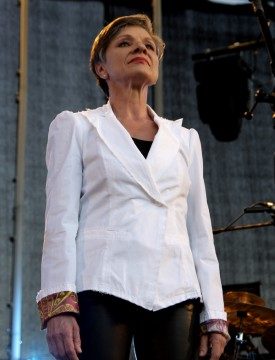

Renate Jett

Austrian actress and singer, known to the Polish audience mainly for her roles in the shows of Krzysztof Warlikowski with whom she has been collaborating for nearly a decade now.

“I came here in September 2001, when we started the rehearsals for the Cleansed then. I arrived with my car in a completely unknown country for me. And I am very glad I made that step then. It still is a ‘grand’ adventure,” Jett says.

Educated in Vienna and Los Angeles, she has worked in many theatres in Europe, including Der Kreis (Vienna) under the direction of George Tabori. In the show Oczyszczeni [Cleansed], 2001, directed by Krzysztof Warlikowski, she performed songs and a monologue which has made history in Polish contemporary theatre as one of the most moving roles. For her role of Caliban in The Tempest in Teatr Rozmaitości Warszawa she received the Aleksander Zelwerowicz Award. In (A)pollonia she sings songs to the music of Paweł Mykietyn.

Kasia Tórz: Vienna, Switzerland, US, Warsaw–out of all the places you lived in, which one reflects your inner self best?

Renate Jett: I’m a part of all the cities I lived in. I like something about each and every one of it, maybe that’s the reason why I couldn’t really decide on one. I like the energy of New York. Vienna is beautiful. Maybe L.A. is the least of my city… I love Paris, but I didn’t live there long enough to make it “mine.”

As far as Warsaw is concerned I wish people were more colorful, but I like how the city has changed since I came here for the first time [September 2001–ed.]. It’s much safer now. I still remember how my CD player was gone from my car the first hour after I arrived. Such things don’t happen anymore. I see much more focus on aesthetics, which wasn’t the case in the communist times.

Renate Jett in Poznań

The longer I’m here, the more I find for myself. I get to know more people, more places. There’s one thing I find problematic. What I like about big cities is multiculturalism, how the worlds meet and mix in such places. Warsaw is rather monocultural. I’m used to seeing many people from very different backgrounds. I miss that here, but I don’t judge it. I understand that it’s an outcome of the past, history, work possibilities. On the other hand, it‘s very interesting how people stick together in their remoteness. Polish Volk [German for “people”–ed.] were always torn apart. Hardly ever an independent country in the course of history. That was probably the reason for the society to become hermetic, enclosed in order to protect itself.

The place where we are sitting now–Blikle Cafe–is one of the oldest and most established cafes in Warsaw. You can catch the spirit of old Warsaw before the breaking line–Second World War. How do you feel this trauma, this big tear?

I will tell you a story which happened to me this morning. The house where I live has 18 floors. I took the elevator with an elderly gentleman. I asked him in Polish what time it was. He showed me his watch. I said “Dobrze czas?” (“Time good?”) and tried to explain in Polish that I have three watches and none of them work properly. He asked me where I come from. Every time I hear this question there is a moment of hesitation inside me when I ask myself will I say “it” or not.

I said:

– I come from Austria.

– Then we can speak German. – he replied.

– Oh. You are from Germany?

– No, but I learned German.

– Have you been in Powstanie? – I asked because many people in this building fought in the Warsaw Uprising. He went silent. After a while, he said that him and his whole family were sent to a concentration camp.– I was imprisoned.

– Why?

– It doesn’t matter why.

– Yes, it does. Are you Jewish?

– No.

– Was it political?

– I was all alone. My whole family died in a karzer.

– Why?

– My father was a socialist and he died for that.

– I’m so sorry – I said.

I left because it was 11th floor already, and he was going further. Just a short meeting in an elevator and such a tragic story. Such situations happened to me so many times. It touches me deeply.

Those traumatic stories seem to be like a trigger in a human being. My grandma is usually very sensible and optimistic, but as soon as she starts to talk about the war, she becomes a completely different person.

Renate Jett in (A)pollonia, Photo S. Okołowicz

My first encounter with Jewish people was when I was a child and I didn’t yet know the history. I got to know it when I was around 12, visiting a friend of my mother’s in England. I went somewhere by myself and I met the first Jewish people in my life. We started talking. They were German, but we spoke in English. When they said that they will not speak German ever again, that’s when I started to understand the dimension of what has happened. It was 1970, 25 years after the Holocaust. I come from Austria, Hitler came from Austria, many horrible butchers in the karzer came from Austria. I feel it every time, it’s very strange, but what can I do?

Still, you do have the courage to face it. Not many people do that.

Some in Austria do. I try to be aware about this Herrenrasse [“the master race”– ed.] as much as I can. The concept doesn’t function only in German or Austrian context. It is a worldwide movement. In America, Argentina the whole Indian population was exterminated just to gain space. It is happening everywhere.

Such stories like the one in the morning, are they influential for your work, for your life as an artist?

If something influences my being, it influences my work. I use these themes in my art. It started with Georges Tabori–Hungarian Jewish writer–who died in 2007. I worked with him when he lived in Vienna, and I learned about the history of Holocaust, Jewish culture, and religion. Just to know more.

After the interview that Remigiusz Grzela conducted with me [W (A)pollonii Spiewam Dla Matki (In (A)pollonia I Sing For My Mother) published in Wysokie Obcasy, Gazeta Wyborcza’s Saturday extra, October 10th, 2009–ed.] something happened to me. I suddenly recalled this girl from my childhood. Her last name was Rosenblatt. I don’t think we ever spoke to each other, but I recalled her very clearly. After forty years! So I called my school to find out, but she “disappeared.” She probably emigrated to America. Whatever comes up I just try to follow.

Do you think the next generations, for example in 2030, will recognize the past culture like that?

I don’t think so. I feel the leading tendency is to destroy, to erase. I fear that something is happening with people’s minds and emotions. This is not the only sort of influence I observe. When I watch SF movies from the 60s and 70s I discover that now we have everything that they had in the movies: we are being programmed, we’re tools of the capitalism and globalization.

…and the technocratic management.

It seems like someone wants to put out such aspects of our humanity as memory, emotions, consciousness, spirit so that people are easy to manipulate, and defined as self-indulgent consumers.

There is this attitude of resentment, which can be dangerous, but it seems like some back up their manipulative actions by taking “resentment” and calling it a “weakness”.

Renate Jett in (A)pollonia, photo S. Okołowicz

One musician from my band said, that “while people are in resentment the next war is happening.” I agree totally. What’s happening is even worse. Looking at only my lifetime I see how the world has changed. I’m the next generation after Second World War. Since the 1960s with the development of the television people have been controlled in a variety of ways: worldwide companies, Lisbon contract… Everybody thinks it is great. I say it isn’t, and I have the need to demonstrate it, but you can forget about it: people are being shot during demonstrations. It happened in Genoa. Genoa for me was the beginning of a new era of totalitarianism.

And the paradox is that it is the demonstration that’s the legal tool to show your objection against something in the democratic system.

They are filming you and know exactly who thinks what. That’s what we called gate-keepers.

I find it very problematic that the society is very passive. Even the young people! As if there was nothing to disagree with. At the university, the leitmotiv is money, career, self-development. And it is these youngsters that should be most critical.

The majority is programmed, true, you are nothing if you have nothing. It pours down the brains from movies and commercials. But there is a lot of young critical and conscious people here. That’s what I really like in Poland.

How is Poland different to Western Europe?

I never see parents who beat their children in the street. Maybe my view is idealized, but I see the love for the children. In Western Europe, I sometimes see brutality towards them. The capitalistic system has been there for a long time, and parents are freaking out because they don’t have enough money to cover all their “hyper-needs.”

I see young people having closer contact with their parents, talking normally. On the other hand, I often notice people not talking to strangers, and sometimes I suffer because I’m a very open person. People are very reserved. I try to understand it. I know what strangers, Russians or Germans, did to the people in Warsaw. What Germans did to this city is an absolute shame. It must have been a beautiful metropolis. I would probably also react this way.

Are you a stranger here, an outsider, are you excluded?

I’m an outsider everywhere. I was an outsider in my family. I was an outsider where I grew up. I’m an outsider in Austria. No sentiment though. I am a stranger even to myself, maybe not as much as I used to be… (laugh)

In your monologue at the beginning of the Cleansed, and in the Tempest, where you played Caliban, I felt that you very creatively made use of that state of being an outsider. It was fascinating.

If I couldn’t deal with it in an artistic way, I would be dead. I would have killed myself. This is a simple answer. It is my chance to be somebody. To own the right to exist.

I’m pondering on this significant opposition: human beings versus animals. Sometimes we say that someone is behaving like an animal–in terms of being cruel or feeling hurt. On the other hand, animals are perceived like having some human attributes. I find it essential when speaking of violence among people, and between men and animals.

It has to have something do with a history full of violence. It is something passed down for generations. I don’t know why people are like that. On the day that the interview in Wysokie Obcasy was released a lot of emotional memory had sprung up. Something was in the air.

Renate Jett, photo by Kaszanka

In the house I grew up there were also grandparents living with their grandson. The parents of the child left him there. The grandfather was beating the boy every single day with a leather belt. I heard the screams. Sometimes I still hear it. So on that day, I called the mother of this boy, old woman now. You know what she said? “Yes. I heard of it. But it was not every day.” Yes, it was, I disagreed. She said “It was not that bad. My father was an alcoholic. That’s why he did it. But the mother was kind.” She is protecting her father who was beating her child every day with a leather belt. Then she said that “the boy was not well behaved.” I asked her, why she gave her child to this tyrant. After that, she said “That’s enough… Thank you.” There was a silence like I’ve never heard before. I had a terrible headache after this conversation.

I’m telling you this because those beaten will love the ones that beat them if they follow the fourth commandment of the Christian Church and ignore the fact of violence. They will also pass it on. Generation after generation after generation.

My dog doesn’t bite me anymore, but it did it often because it was beaten a lot. It was hard for me for nine years, but I did not give it away, and I tried to love and love and love. This is something inside. It’s similar with people.

Where do you draw the distinction between fiction and reality? Your singing and stage performance is very oneiric. In (A)ppolonia one minute you’re in the spotlight, another you melt with the background singing very quietly, whispering your hypnotic song.

It is metaphysical. This is trance. There was a time when I divided acting from the “I.” I played a lot of different roles. But it was just parts. With some I had fun, others were closer to me. But still, there was this professional division.

The turning point was meeting Tabori. I understood that there can be a connection between my story and the parts I play. I’ve gained a new view on acting, theatre, being on stage. There is a lot of performers that claim that the parts they play have nothing to do with their private life. They just go on stage, turn into somebody else, and then go back.

It took me a long time to understand and connect my body with the parts I undertake. I believe that trance can provide you with a lot of information about yourself, about life. It is like this twilight zone. I don’t know what Sufi do in their dance or Haitians in voodoo. I have my own method. What I receive is feedback on my subconsciousness. It’s very important for me to release it. When you go into such a condition there is the space for it to appear. That is how I work. I must tell you I know nothing about acting. Because I don’t think in such terms anymore. It has a lot to do with trust–in life, in people. This is what I’m still learning.

This post originally appeared on Biweekly.pl in July 2010 and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by biweekly.pl .

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.