It all starts innocently enough. Two actors (Damian Sosnowski and Alan Al-Murtatha) and an actress (Natalia Bielecka) take the stage. They are dressed in loose, everyday, dark-coloured clothing. The director, Wiktor Bagiński, seated near the audience, gives them general prompts (for example: ‘Open your fields of energy,’ ‘Become water, air, fire and earth’), and switches on intense, rhythmic music. They dance. First alone, then – according to the next command – interacting with each other. Eventually, their bodies, still in constant motion, intertwine with one another on the floor. In this simple, surprisingly long scene, which opens the performance, a few things stand out as important. First – the fatigue of the actors, who are stimulated by the director’s imposition of these themes and of the dynamic of the movement, as well as its duration. Second – the intensifying physical contact between them as they dance. Third – the potential embarrassment of the audience, who have no concrete framework to help them understand the ongoing and excessively prolonged process happening onstage, which may give them the impression that they are observing a dance-movement therapy session, or a rehearsal, where the director is trying inordinately to tire out, and then to emotionally and physically open up the group he is responsible for.

The second feeling grows more intense when the next command is spoken. Two people are to gradually undress a third person, until that person says ‘stop’. Some end up standing in their underwear; others only allow their shirt to be taken off. In any case, the decision of the person whose clothes are being removed is binding and non-negotiable. This is similar, however, to the tasks imposed upon them. All of these relationships and strategies – beginning with the director’s crossing the actors’ intimate boundaries, yet also allowing them the space to mark their own limits of this intimacy, much to the audience’s confusion – determine the thematic scope of Otello [Othello] [1], in which such constant commentary on the staging strategies used in the performance serves to problematise theatre itself. The performance, created as part of the Directing Department exams at the AST National Academy of Theatre Arts in Kraków and presented during the Young Directors’ Forum, where it was awarded the 2019 TR Debut award, is the latest artistic work (and the latest created at this institution – alongside the presentations of #Gwałt na Lukrecji [#The Rape of Lucrece] and the text Aktorki, czyli przepraszam, że dotykam [The Actresses, or Sorry for Touching You]) which takes up the #MeToo movement in the context of education and artistic creation at the Directing Department of the AST National Academy of Theatre Arts in Kraków.

#Gwałt na Lukrecji (#The Rape of Lucrece), directed by Marcin Liber, AST National Academy of Theatre Arts in Kraków, 2018. Photo: Bartek Cieniawa.

In the subsequent scenes of Otello, the dramaturgy shifts dramatically. Natalia Bielecka sits on a chair, rather close to the audience, and begins to tell a story. She talks about an evening that she, together with the other creators of the performance, spent at a club – drinking, dancing and talking. Late in the night, they decided to go for an afterparty at the home of Wiktor Bagiński. They drank more. When the alcohol ran out, Wiktor and Alan went to the store, and she stayed there with Damian. They started to joke, and her friend danced for her. She was too drunk to reciprocate. Then, Damian, paying no heed to her protests, decided to make a move on her. She was wearing a dress, so he removed her underwear without difficulty and began to (and I’m quoting here) ‘fuck’ her. When the other partiers returned, Natalia pretended like nothing had happened. This pretending for herself and for others continued up to the point when Wiktor proposed that everyone at the party collaborate [on a performance] for the [upcoming Directing Department] exam.

The topic of Otello sparked personal conversations [amongst the creators] about complicated, emotionally charged accounts. After one of the rehearsals, Natalia received a message from Damian saying that he remembered that night very well. After this, she realised that the rape which she had tried to deny had in fact happened. She decided to talk to Wiktor and Alan about it. Then, she heard from the director that she should turn this experience into art. Bielecka speaks with no ‘actorly’ affect; she falters and stammers throughout; she looks down, but sometimes, she looks at the audience, as if to gauge their reactions. Choices like using the personal names of the creators, or putting the process of the very production which is being seen at the centre of the plot, make her story sound quite credible. Listening to her, you can really wonder why this woman is addressing these words to the theatre’s public, rather than going to the police. It’s important to remember, however, that we are participating in an artistic event – such that any faith in the words the actress is speaking is, at the same time, a sign of naivety. The awareness of the theatrical fiction subdues the events which follow. From his phone, Alan Al-Murtatha reads a poem that he wrote, influenced by the director’s prompt on turning trauma (in this case, not his own, but that of his friend [Natalia]) into art. Meanwhile, Damian Sosnowski opens the window and attempts to jump out of it. He is stopped by Alan, who, whilst shouting the words of his poem, grabs ahold of him. The situation grows more and more grotesque. And the theatrical convention becomes even stronger in the next scenes, which the actors perform in Elizabethan-style costumes.

A paraphrasing of [Shakespeare’s] Othello follows, in which the actress and actors repeat – one at a time, over and over again – the phrase: ‘I have a terrible runny nose today’, more and more insistently asking for a handkerchief (which is a large, colourful tapestry) whilst Alan Al-Murtatha talks about the cultural strategies involved in othering a black person. When, in watching these theatricalised scenes about jealousy and intellectual analysis, we finally breathe a sigh of relief, the topic of the rape returns. Natalia Bielecka walks the director onstage and delivers rhythmic blows to his cheeks. Damian Sosnowski stands, quite naked, over the actress, who is lying in her dress, and, using a sheet of paper, he reports the events of the evening in question, point-by-point. Many important issues – like the course of the events (clearly, he is romanticising the situation) and their location (room or bedroom, sofa or marriage bed?) – simply do not add up. That the woman was very drunk, and that he raped her, are not subject to verification… It’s worth emphasising the obvious, but often-questioned thing: a lack of clarity in rape testimonies, typically associated with the experience of shock, disorientation, shame and fear, is not an indication of lying. Next, there is another highly ironic scene – except that here, the irony takes on an increasingly bitter dimension. This time, Natalia reads a poem which describes her inner state. When she finishes, Alan – as an older friend – gives her a condescending lesson on speaking on stage. With a sweeping gesture and rhetorical exaggeration, he utters the phrases she has written in order to make them sound more poignant. Her experience has been taken over by a man (the director having previously done the same) and turned into something ‘more interesting’, ‘more convincing’, by him – ‘art’. The actress doesn’t listen – she walks out of the theatre hall through the audience entrance. The show ends with Damian singing and playing on the guitar the song ‘The Kill’ by the band 30 Seconds to Mars. And he, as we can see, has transformed his own experience into effective ‘art’. In the meantime, this performance about rape has been dominated by men, its finale performed by the perpetrator…

Such a detailed description of this performance is needed due to its aforementioned, indeed persistent level of self-referentiality. Otello is happening all the time, constantly thematising itself and talking about itself. Incessantly playing with fiction and reality, it puts the viewer in a highly uncertain and thus uncomfortable position. Should we believe the story? It sounds – as I mentioned – quite credible. If it is true – and if it does concern the people we see on stage – how are we to understand it, to accept it? Should we reject it, as an acknowledgement that such issues should not be the subject of artistic creation, but rather of a police investigation? Fine, but do we have the right to tell a woman who has been raped how she ought to deal with this experience? On the other hand, isn’t to re-forge rape into the subject of a performance somehow to normalise it, to turn it into a tool of legitimacy and consent? Besides, how can we be sure that she didn’t go to the police, that she didn’t hear questions about the amount of alcohol she consumed that evening or her choice of outfit? Or perhaps her colleagues persuaded her straightaway of such a solution – in the name of friendship and art, or even of the good name of AST and of her career? How did the instructor react, in whose classes this performance was created? Did he investigate the truth and – regardless of the truthfulness of the story – offer the team a consultation with a psychologist (if only because of the topic the performance takes up)? And what of this accused lad? Is a public performance of bringing charges and pleading guilty a kind of punishment in and of itself? Is it even possible for him to agree to such a thing? On this level, the performance also indicates a process of transferring an accusation, and an imposition of punishment, from a court to a public space. This vision is, of course, disturbing and dangerous, but in light of the inefficiency of legal procedures and practices [in this domain] – it is also depressingly understandable (although, as it turns out, it can also be ineffective and backfire for the prosecutors themselves). [2] But, once again, I’ve gone too far! This is a performance, theatre, fiction – and a very effective inducement of the ‘authenticity effect’, which, moreover, appears to draw inspiration from Thordis Elva, who wrote the book South of Forgiveness [3] and conducted a series of talks with the person who raped her (who was also her first boyfriend) – Tom Stranger. Then again, it’s worth remembering that the method of transforming a painful, personal experience into art is repeatedly, ironically and ruthlessly ridiculed in Othello… Here, however, other doubts emerge. What is the difference between turning one’s own trauma into art versus ‘processing’ that of another? The very slowly disclosed stories (and mostly in performances, plays, gossip – rarely in the form of real complaints) of sexual violence in theatres and art schools, which have occurred and undoubtedly continue to occur (and not only in Poland, of course), testify as to how often people who experience sexual violence remain, for years, in professional, symbolic, and psychological relationships with the perpetrators. Beyond that, trauma is often fetishized in the context of acting, used by directors (men and women) who make it into a centre of the artistic process. Exactly as it is shown in the performance. The scene where Bagiński is slapped is an effective confirmation of this thesis. This eloquent stage gesture of accusation and revenge, however, conflicts with the fact that the TR Debut 2019 award at the Young Directors’ Forum in Kraków was awarded only to Bagiński – and not to the team…

Thus, the performance casts an ambiguous light on the practice of art taking up the topic of #MeToo in the theatre. As I was watching Otello, I remembered one of the scenes from Casting! [4], in which the actresses, who are making a performance about #MeToo, call their other women friends who are actresses, looking forward to the subsequent stories of sexual harassment that they will then be able to use in the performance (‘So that it will be more documentary and more precise / Based on biography / Based on facts’ [5]). Thus, they pose an important question as to whether #MeToo-themed art isn’t a substitute for real action in Poland and whether acquiring symbolic capital from the painful experiences of friends isn’t somewhat ambivalent in and of itself. Artistic risk, after all, is safer than real risk. By realising an artistic work about #MeToo, one gains approval; by [actually] doing #MeToo – one risks losing one’s job, social ostracism, a drawn-out trial. A gesture, one requiring great courage and determination, by the women employees of the Bagatela Theatre who decided to accuse the director of mobbing and sexually assaulting them for years, was met with solidarity from the community – expressed in letters of support, meetings, panel discussions and artistic works (such as Monika Drożynskiej’s embroidery #ME TOO / IS TRU / SOLIDARITY WITH BAGATELA), as well as activism (such as the activities of the Plakaciary Przeciw Przemocy [Women Posterers Against Violence] group, who posted slogans like ‘Sexism Kills’ and ‘The Women of Bagatela Are Superheroes’ [6]). They also saw hate from the internet, on the streets and amongst their friends. [7] Whether other women and men, from large or smaller cities, from more entertainment- or art-oriented theatres decide on public #MeToo movements or not (for there is little doubt that Bagatela is not a sensation), the course of this matter itself will have a greater impact than any – even the best – performance.

In this context, it’s worth revisiting a similar case that took place at the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries in Wrocław. An accusation of sexual assault (‘Zbigniew L. […] kissed, grabbed [their] breasts and buttocks. He forced one of them to touch his exposed genitals’ [8]) made against the director Zbigniew Lesień by seven employees of Teatr Współczesny was authenticated by the court seven years after it was filed (the investigation was discontinued twice, and only later did the case go to court). In 2001, there was a first conviction, which found the accused to be guilty, but the court ‘did not impose a penalty upon him due to the act’s low level of societal harm’ [9]. The verdict was impossible to enforce, so – at the initiative of the accused, who wanted to be cleared of the charges – two more trials were held. Finally, in 2005, Lesień was given a year’s sentence: ‘This means that Zbigniew Lesień will be punished if he commits a similar crime within a year. No punishment has been imposed, because the former director of Teatr Współczesny enjoys a good reputation and has not previously been convicted. Lesień will be required to pay 3,000 zlotys to the Children’s Home in Kąty Wrocławskie and to reimburse the legal costs of each of the injured women’ [10]. Despite the weight of the complaint and the legal victory of the women employees, the punishment, disproportionate in relation to the charges, as well as the outrageous justification of the first judgment regarding the ‘low level of societal harm’, could have significantly influenced the fact that this case did not lead to any subsequent cases. The dynamic proceedings of the trial, which were widely publicised in the media, might lead one to believe that, in recent years, with the influence of the global #MeToo movement, something must have changed…

Let’s return to the question, however, that if a real-world court case has a significantly greater motive power, does it mean we ought to stop creating art related to sexual assault in the theatre? And if people who experience assault don’t want to talk about it in public, does theatre become a valve through which the problem, and the mechanisms of its normalisation, can at least be brought to light?

This thread is taken up in the aforementioned Casting! At the end of the performance, there is a scene in which the viewers are to decide which of the ‘testimonies’ of assault, sexism and discrimination that have been presented are true, and which simply constitute a non-credible situation of ‘one word against another’. Those who saw the earlier performative reading of Pięść [Fist] [11], based on a play by Anna Sokolicz, know that all of the stories – regarding harassment both in the family and in the Church – had already been told by Katarzyna Szyngier in a personal #MeToo recording. There, spoken by Szyngier directly to the camera (the film was also shown in the reading), they sounded overwhelmingly sincere. Now, inserted into the framework of a theatrical fiction, performed by actors and consciously put into question, they lose the weight of a confession, becoming instead an instrument of theatrical play.

Here, however, they are also used in a different way than in Pięść. The artists seem to be shifting part of the responsibility for the staged situation onto the viewers. And this is not only about deciding upon the story’s truth. In presenting this material, Karolina Micuła goes out amongst the audience and directs some of her obscene, aggressive comments straight to them, sometimes coming dangerously close to them. The situation is very uncomfortable – I suppose – for both the people to whom these actions are directed as well as the observers. Ought we to react? Where does the border of artistic fiction end and real harassment begin? While these stories could be fictitious (although they are not), the actress’s hands on an audience member’s knees are by all means real… I was at both showings of the performance – and no one, including myself, reacted. We behaved exactly as in the story told as part of this event, in which Katarzyna Szyngier and her friends (men and women) from class did not react when Mikołaj Grabowski put his hand under her skirt whilst explaining how one ought to work with actors. I got the impression that, through this risky and problematic gesture, the creators of Casting! were attempting to create a real experience within the environment of the performance in order to make the topic of assault more concrete in relation to the audience. It’s a pity that the range of this event was quite small – the performance was presented twice, omitted in the PPA’s [Przeglad Piosenki Aktorskiej’s] decision and quite poorly described. [12] (Although perhaps Szyngier’s recording from Pięść as well as Casting! and other events of the #MeToo movement work on the principle of synergy?)

This is the rather ironic thesis presented in Casting!: ‘Now to conquer meaning / the documentary part / it’s about / that when we check something / then, when someone tells us truly / then, when people feel it / and when it has such power / the action / is unprecedented’ [13]. This came true, however, in the case of Michał Telega’s text Aktorki, czyli przepraszam, że dotykam [The Actresses, or Sorry for Touching You], which came out of the Directing Department in the context of Iga Gańczarczyk’s classes. In this case, the greater level of agency of a choir [so to speak], as opposed to that of individual voices, was confirmed. Based on interviews with acting students, across all of the class years, regarding sexual harassment in the education and professional practice of young actresses, it has led to a series of real actions aimed at preventing violence and discrimination at the AST National Academy of Theatre Arts. The script was written for class credit and is – as the author informs us – ‘a record of mixed statements from students at the Academy of Theatre Arts […] It was created thanks to the kindness of representatives of each class year, who previously gave their responses to nine open questions’. It’s worth noting that the group of actresses was chosen randomly, not based on any knowledge on the part of the author that they had experienced discrimination and sexual assault. The questions concerned, amongst others, gender-based discrimination and the actresses’ attitudes towards their own bodies, as well as instances when the boundaries of intimacy had been crossed at the theatre school, during castings and in theatre and film. The author also asked if actresses have the courage to protest and talk openly about sexual assault. The answers testify to the scale of the problem – at school, as well as at castings and during work in the theatre (‘I was in it and others too’ – p. 9). There is a fear of disclosing it, because, as the students say, ‘we wouldn’t want to run into problems later’ (p. 3). Their statements are mixed with frustration and a determination to break the silence, because ‘how much can one passively remain and endure humiliation?’ (p. 3), as well as a sense of giving up, because ‘nothing will change / there’s no point / women will always be sexualised’ (p. 12). There is also the question of whether a complaint about sexual harassment isn’t an indication of oversensitivity and of a misunderstanding of cultural realities: ‘maybe, between this feminism and chauvinism, we’ve gone too far / maybe that’s just how people talk’ (p. 10).

The title phrase, ‘sorry for touching you’ (the person who [reportedly] said this no longer works at the school [14]), is repeated like a refrain in various contexts throughout the play. The situations which are described relate to, amongst others, taking advantage of classes, castings or creative work in order to persistently touch actresses: ‘he takes advantage of his position’ (p. 8); ‘he approaches me and touches my breast […] not the sternum, where the movement comes from / he doesn’t ask if he can / he comes up to me and touches my breast’ (p. 8); ‘he grabbed me by the chest, by the ass / he could say / he touched me where I felt that he wanted to touch me’ (p. 8). Such behaviours were justified by ‘transgressing physicality / but in the name of art’ (p. 9). The actresses also quoted language full of sexual allusions; ‘play it from your cunt / you’ve probably never fucked / imagine that you’re giving a blowjob / where are the cunts, cunts on stage / you are all whores’ (p. 9). The text also includes explicit examples of gender-based discrimination. From the fact that ‘texts like these would never go to the boys / they were fucked up by the work, but they never crossed a line’ (p. 11); to the manner of treatment – ‘he treated men / as if they were savvier’ (p. 18) – to the discrediting of the opinions and artistic work of women: ‘he listened to what a colleague had to say / and when I proposed something, he dismissed it and dropped it / as if he were fighting with me / fighting for his opinion to be on top’ (p. 10); ‘he said that no woman had ever written a good play’ (p. 10); to the appraisal of the work – ‘recently, I keep hearing “the women are hopeless, the men are fantastic”’ (p. 12) – and salaries: ‘men in this profession are better paid’ (p. 14). There is a constant through line of inhibiting the development of actresses by casting them ‘conditionally’ on the principle: ‘whatever doesn’t play, you can make up for with your looks’ (p. 6).

It’s worth noting that the actresses who spoke with Telega do not appear to be categorically opposed to nudity and intimacy in art (‘my body is / a tool / an instrument / […] / to undress / – / I don’t know if I would agree / here, breasts … okaaaay / but down below / I would have to think about it / I have no problem with it … I think’ – p. 6). They object, however, to how such scenes are worked on, using art as an excuse for sexual assault and for reducing actresses to the role of sexual objects (‘from the beginning, we are taught / but this is not always the right approach to teaching / sorry for touching you’ (p. 7); ‘I had to pretend to have an orgasm / a cool barrier to break / but as I’m performing it / I would like more / not just [to perform it] erotically’ – p. 15).

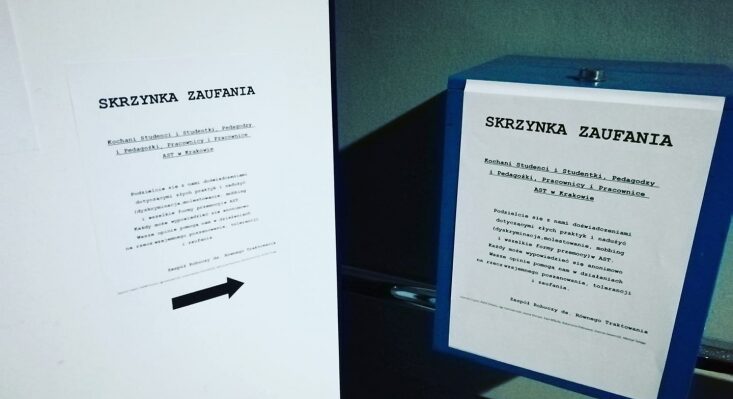

‘Skrzynka Zaufania’ (Trust Box) at the AST National Academy of Theatre Arts. Photo: Michał Telega.

Aktorki, czyli przepraszam, że dotykam describes, in an unusually suggestive, condensed and multi-faceted way, how the mechanisms of abuse and submission implemented at school are reproduced in theatre and film – both by those who ‘can’ touch and by those who passively endure this touch. The sharpness of the descriptions and perceptions of the actresses also show, however, that they are absolutely aware of the violence of the mechanisms to which they are subjected. I would guess they wouldn’t ever say, as Tracy Oberman did in describing, after many years, the sexual harassment she experienced from Max Stafford-Clark – the former art director of the Royal Court:

It was humiliating and disconcerting, and given my lack of professional experience at that point, I found myself looking around the room and thinking that this must be normal. This must be what being an actor is like.

Despite this, they reported their experiences only as part of an anonymous questionnaire, and not as an official complaint, because ‘I can be treated even worse / […] / harassed / persecuted’ (p. 16). The question is, to whom are they to turn with such a complaint?

After the exam, during which the text of Aktorki was read, Iga Gańczarczyk – the deputy dean of the Directing Department, Iwona Kempa – the dean of the Directing Department, and Michał Telega sent a letter to the rector of AST, Dorota Segdy, for the appointment of a spokesman for equal treatment, as well as for the creation of a University Code of Ethics. Several months later, an Equal Treatment Working Group was established at AST; in-depth interviews were conducted with students, both men and women (including at the school’s branches in other locations); and a ‘trust box’ appeared at the school, bearing the information: ‘Share with us your experiences of bad practices and abuse (discrimination, harassment, mobbing and all forms of violence) at AST. Anyone may comment anonymously. Your opinions will help us in our efforts to promote mutual respect, tolerance and trust.’ So it’s not that art has no impact on reality, that it is always an act of substitution. I won’t hide, however, that I would prefer that the #MeToo movement come into being more fully in theatrical institutions themselves than on stages and in texts, because already, I have a sense of real disproportion.

At a meeting with directors during the Young Directing Forum, Wiktor Bagiński reportedly said (I know this only from accounts, as I was not at the meeting) that the story told in the performance [of Otello] is a hoax. Can we all breathe a sigh of relief? I don’t think so. Because it’s worth asking: why is this information important or even necessary? Apart from all of the other issues, including those already described in the text, this is a good thing – since the performance is affiliated with AST, we probably ought to have confidence in an institution that thoroughly researched the story behind it – which is about people studying there and describes creative processes taking place within it – before including it in the programme of the Young Directors’ Forum. (For does the fact that the violence occurs between students, and does not involve the person conducting the class, mean that the school ought not to take an interest in it?)

But can I have such confidence in a school where – as demonstrated in ‘Harassment at Polish Public Universities’, a report by the Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights – no sexual assault was reported for an eight-year period (2010-2018)? Were there no reports because there was no abuse? Unfortunately, Michael Telega’s text; a survey by Alina Czyżewska regarding violence in theatre schools, the very disturbing results of which were presented during the conference Zmiana teraz! O czym milczeliśmy w szkołach teatralnych [Change Now! What We Keep Silent About at Theatre Schools] and published in Polish Theatre Journal 15; as well as Katarzyna Szyngier’s story about Mikołaj Grabowski’s behaviour would all strongly contradict such a thesis. Perhaps there were no reports because there were no procedures for submitting them, because there was no awareness for which behaviours could be subject to them? Were there reports, but were they not revealed in this paper so as not to, for example, jeopardise the good name of the school, to have the pedagogues removed as a result of these complaints (who, due to confidentiality regarding the reason for a dismissal, could still work in another private or public school)?

Do I trust this institution? I may gain it when the AST Code of Ethics is created, when the Equal Treatment Committee ceases to be ‘Working’ and when all of the procedures and documents are published (at the moment, I’m not able to find information about current procedures on the school’s website or official profile on Facebook [18]) and implemented in a series of trainings. Yet this is not to mention special procedures for working on scenes of intimacy with the participation of what are known as ‘intimacy coordinators’, as presented at a Warsaw conference by the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland. [19] Maybe when cases of abuse begin to be reported, documented – if only to investigate the actual scale of the problem and to not underestimate it – and when the anti-discrimination policy of the school is based on openness, and not on shaming the victims with the notion that their complaints have disturbed the general harmony, which they may feel. And when discussing such regulations, let’s remember not to victimise women students, because the Code of Ethics is also intended to protect students who are men (very few men working in Polish theatre have made public – mainly Facebook – #MeToo statements, which does not mean that the problem doesn’t exist) or the people who conduct classes (I assume that they are also the victims of various kinds of violence). I very much hope that not only AST, but also other theatre and film schools [21] and theatres [22] will strive for such solutions – as have already been implemented at the Theatre Academy in Warsaw [20]. As a spectator and as a scholar, I would really like to stop feeling this constant anxiety about the conditions of the performances I create and the educational processes that precede them. With this knowledge, which we all have now, I unfortunately cannot… And writing such texts as this one is (for me) a process that is quite emotionally difficult and unsatisfactory. Just as the little-satisfying fear of their publication…

Footnotes:

1. Directed by Wiktor Bagiński; set design: Anna Oramus; cast: Natalia Bielecka, Alan Al-Murtatha, Damian Sosnowski (showing: 15 November 2019).

2. A recent example of the inefficacy of the law and the risk involved with speaking publicly about violence can be seen in the case of Agnieszka, whose husband, contrary to testimonies, expert opinions and medical and gynaecological documentation has been cleared of allegations of marital rape. She, in turn, was found guilty of defamation for having posted about the crime on Facebook. The case was analysed by, amongst others, Maja Staśko in the article ‘On został uniewinniony za gwałt. Ona – skazana za napisanie o gwałcie’.

3. See Thordis Elva and Tom Stranger, South of Forgiveness (New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2017).

4. Weronika Murek, Casting!; directed by Katarzyna Szyngiera; stage design, costumes: Agata Baumgart; music: Kama Salach and Karolina Micuła; choreography: Agata Obłąkowska; cast: Agata Obłąkowska, Karolina Micuła, Kama Salach (Przegląd Piosenki Aktorskiej w Wrocławiu, Nurt OFF, showing: 28 March 2019).

5. Script of the performance made available by Katarzyna Szyngier.

6. See Angelika Pitoń, ‘Pracownice Bagateli to superbohaterki. Plakaciary i ich miejska akcja’, Gazeta Wyborcza– Kraków, 16 January 2020.

7. Małgorzata Skowrońska and Aleksander Gurgul, ‘My, kobiety z Bagateli’, Wysokie Obcasy, 23 November 2019.

8. Krzysztof Kamiński, ‘Wyrok w sprawie molestowania w teatrze’ in Słowo Polskie Gazeta Wrocławska,12 November 2004.

9. Ibid.

10. ‘Trzeci wyrok sądu w sprawie Zbigniewa L.’, Słowo Polskie Gazeta Wrocławska, 1 April 2005.

11. Zbigniew Raszewski Theatre Institute, as part of the Scena niepodległych kobiet series (premiere: 15 November 2018).

12. Katarzyna Lemańska has written extensively about this in ‘Tajemnica poliszynela’, Didaskalia nr 154, 2019.

13. Script of the performance made available by Katarzyna Szyngier.

14. See Iga Gańczarczyk, ‘Testimonies and Declarations’.

15. Czyżewska does not specify in the text which schools each statement concerns; during the conference discussions, however, she signalled that some of them referred to AST. This is also confirmed in an interview given to Aneta Kyzioł – when, commenting on the conference, the methods used in theatre schools and her survey (she offers examples from it), she says: ‘And anecdotes like the one about a Kraków professor who has been telling women students to simulate orgasm or masturbate and speak a text on this “emotion”’. This is his only “method” of teaching a monologue and is supposed to open and break barriers’. (‘Przemoc nie bagatela’, Polityka no. 2/2020, p. 82); Czyżewska most likely refers here to the statement she quotes in her text on page 4.

16. ‘We learned that in the past there were instances of teachers’ inappropriate behaviour in the Faculty of Acting, and complaints from male and female students had led to the dismissal of at least two people. One of them was the author of the expression “Sorry for touching you”, well known in academy circles.’ – quote from Iwona Kempa, ‘What to Do with What Is Now? At School and in the Theatre’.

17. The mechanism for building an institution’s brand in suppressing information about sexual offenses committed there is portrayed well in a documentary film about American universities, titled The Hunting Ground (directed by Kirby Dick, 2015).

18. Information from 2 February 2020.

19. Vanessa Coffey, Hilary Jones, McCallister Selva and Thomas Zachar, ‘Shifting the Landscape: Why Changing Actor Training Matters in Light of the #MeToo Movement’. Regulations concerning, amongst others, scenes of intimacy have also been introduced, for example, by some American theatres: cf. ‘Chicago Theatre Standards’, 2017.

20. See information concerning ‘Rzecznik Praw Studenckich AT’, ‘Kodeks Etyki Akademii Teatralnej im. Aleksandra Zelwerowicza’ as well as Agata Adamiecka-Sitek, Agata Koszulińska, Marta Miłoszewska, Beata Szczucińska, Weronika Szczawińska and Małgorzata Wdowik, ‘Allies: How We Broke the Silence and Made Documents’.

21. A conflict has also recently emerged between the students and officials at the Łódź Film School, which has revealed different attitudes on both sides towards the #MeToo movement. The rector rejected a petition by students (amongst whom are who declare that they have experienced sexual violence) to cancel a meeting with Roman Polański, who has been accused of sexual offenses. The rector explained his decision in relation to, amongst other things, the guest’s outstanding artistic achievements (See ‘Justyna Kopińska o sprawie Romana Polańskiego: mówią, że ksiądz zgwałcił, a reżyser “przespał się”’.)

22. The wave of investigations and discussions about the Bagatela Theatre includes calls to ‘set up a special initiative that will develop procedures for reporting similar cases and a code of conduct’, which would include ‘psychologists, sexologists, lawyers, sociologists and members of creative organizations’ – see Iga Dzieciuchowicz, ‘#MeToo w polskim teatrze i co dalej?’.

This article was first published in Polish by Dialog 2/2020 (759). It was translated into English by Lauren Dubowski for TheTheatreTimes.com and reposted with permission. The translation was supported by Polonia Aid Foundation Trust.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Monika Kwaśniewska.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.