Rather than experimental theatre, it is the realm of dance works that is considered to be much more amenable to music and its ability to guide or transform a live performance. It is as if the body can only respond to the suggestible registers fed to it by soaring melodies or beats. Yet, recent excursions in contemporary dance have attempted to entirely dispense with sound altogether.

Sounds of silence

Instead, a vast unstarched expanse of silence becomes the ether in which the performers must discover their corporeal alter egos. In Avantika Bahl’s Say, What?, she interacts through gestures with deaf performer Vishal Sarvaiya, using both signage and figurative motifs. The conspicuous omission of a score was perhaps mandated by the need to mirror the quietude of Sarvaiya’s world, thus achieving a facile congruity that placed the performers on even ground. At Delhi’s Max Mueller Bhawan, choreographer Navtej Johar recently showcased a looped presentation that featured students of his six-month-long workshop on somatic techniques. The lack of musical texture left the performers free to be guided by the energies within their body, letting their muscles respond to their own native sensations—a principle that lies at the very core of a somatic experience.

In contrast, the parallel culture of theatre appears to be in the midst of a melodic renaissance. It is certainly the open season for musicals. Accompanists are part of every entourage, and many have fan followings of their own. Movement theatre is riding a wave, even if it sometimes entails plonking an unprovoked dance interlude right in the middle of an otherwise conventional staging. World music excavated from obscure geographies (Eastern Europe, in particular, lacks a copyright regime) accompany said interludes. Although mainstream film music is still largely a no-no (licensing fees can be prohibitive), the language of cinema is increasingly finding favor with theatre-makers especially the immersiveness that can be achieved with a sweeping musical score. In most cases, this comes with the turf of certain genres. But, naturalistic works worth their salt have traditionally eschewed the use of music, at most employing the sounds of quotidian life—the click and the tick and the tap and the thud—to create soundscapes that mirror the worlds we live in. In these productions, dramatic moments need not be garnished with musical inflection. Sometimes, the music is a cop-out that lends a helping hand to actors lacking in rigor.

Resonating trends

However, from recent evidence, the musical score is here to stay, as perhaps another sop to the waning attention span of the average theatre-goer. Original music composed especially for the experimental stage is now increasingly being taken as a given, much like a play’s light design or sets. Hearteningly, there have been quite a few productions that illustrate excellent use of music. For instance, in the electrifying opening sequence of Deepan Sivaraman’s Khasakkinte Itihasam, it is as much the amped-up decibels of Chandran Veyyattummal’s score as the slow march of actors with burning brushwood in their hands, that triggers the rush of adrenaline that will see us through the play’s 205-minute running time. It is a contemporary sound, in that it does not cater to our expectations of mustache-twirling melodrama, yet it suffuses the enterprise with a primeval quality that marks out the village (in Khasak) as the fountainhead of what is to give shape to modern Malayali culture. Caught in its own time-warp, Khasak reaches out endlessly into the future and only on one occasion does Sivaraman add an existing reference to the music’s period flavor—a popular 1950s era song from the film Neela Kuyil—to great effect.

A few other stage symphonists come to mind. Composer Naren Chandavarkar, fast growing into an indie cinema mainstay, made an early foray into theatre with Nayantara Kotian’s The Skeleton Woman. Last year saw him add to the dystopian atmosphere of Rehaan Engineer’s adaptation of Caryl Churchill’s Far Away, by tossing out natural progressions to work with dissonances and inverted tones, which come to a head during a pivotal set-piece in which inmates of an asylum, each decked up in outlandishly crafted pieces of millinery art, walk towards what could well be a giant incinerator.

Another indie regular Anurag Shanker substantially contributed to Atul Kumar’s Khwaab Sa, an unorthodox retelling of William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Staying true to the play’s dream-like ethos, that unpredictably flits in and out of seemingly unrelated scenes, Shanker conjures up a soundscape (or perhaps, a dreamscape) touched with gravity and light-heartedness, slumber and wakefulness.

More than words

Perhaps there is no one as prolific as Kaizad Gherda, who was seen as a live musician in Manish Gandhi’s Cock and Sunil Shanbag’s Club Desire and has composed music for a dozen-odd productions and counting. One of his latest outings was for Arghya Lahiri’s Wild Track, and his sounds, both musical and elemental, bewitchingly waft in and out of the play’s narrative, never intruding, but always an undercurrent that we are constantly accompanied with. Ennui is big in today’s theatre, and Gherda certainly has a hand on the resonances of a big city, and what is excluded from it.

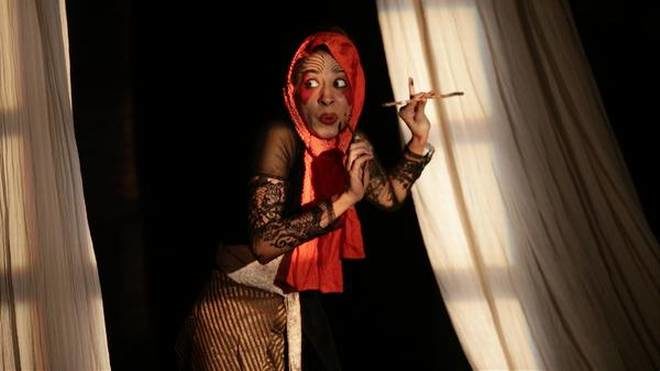

Bahl’s earlier dance piece, {Wonkot}, had featured an impressionistic score by Seemingly That, the label that is the brainchild of musicians Adriel George and Pruthu Parab. In that piece, they had included a track called Elephant In The Room—the piece itself was based on Rumi’s The Elephant In The Dark. This week, they are back on the stage with Yuki Ellias’ similarly named The Elephant In The Room, for which they have composed an aural landscape that accompanies the adventures of Master Tusk, a stand-in for Ganesha himself. It is certainly a cinematic score, full of flourishes and crescendos, but it seems to be almost magically ingrained in the mists and depths of an Indian jungle. The play also boasts of Ellias’ formidably modulated vocal-work, as she voices one majestic character after another. Close your eyes and it sounds like a Pixar adventure in full swing, replete with humor and bombast, and the lower reaches of a soundtrack that never appears to fail the story’s best moments.

The Elephant In The Room was staged at Prithvi Theatre, Juhu, on April 18 and 19, 2017, at 12 p.m., 4 p.m. and 9 p.m.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Vikram Phukan.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.