Svetlana Alexievich’s Voices From Chernobyl collected the testimonies of survivors from the nuclear disaster: military personnel, medical professionals, and, most importantly, ordinary people. Her book is a series of stories that tell the untold: how little the people in the Soviet Union, and especially the Ukraine and Belarus, knew about what happened the night the reactor in Pripyat’s nuclear plant caught fire, emitting a glow that drew people onto their balconies at night to watch the reactor burning, amidst a cloud of spreading, deadly radiation. Adapting Alexievich’s work into a play seems a monumental task: what to focus on? How to present these voices on stage? But at Cockpit Theatre director Germán D’Jesús has risen to the challenge, creating a brilliant piece of theatre that uses only the original text.

In a mix of Russian and English, six actors present different stories from the book. Standing on a bare stage with few props, they tell us about the initial fascination in Pripyat that night, the horror of radiation experts finding out that a radioactive cloud was moving towards Belarus, ignored by the authorities. And the stories of soldiers who attempted to put out the reactor-fire, throwing graphite and sand into the smoldering pit below. In first-person narrative throughout, Voices from Chernobyl is a tale of black jokes (‘There are two kinds of men: radioactive and radiopassive’), of disfigured children, of families torn apart by a deadly enemy they couldn’t understand: is radiation still there if you lock the doors? How can something invisible be such a lethal threat?

Throughout the play, two narratives emerge: that of women having to bear the deaths of their husbands and the disabilities of their children, never quite knowing what caused it; and of soldiers and firemen aware their lives would be cut short by contact with the reactor, but also knowing that if they failed in their duty the catastrophe would multiply, making much of Europe uninhabitable. All this under a ruling system that valued communist loyalty more than people’s lives, fuelled by cold war propaganda.

The rapid succession of the stories, brilliantly evoked by D’Jesús and his actors, emphasize the confusion and the clamor of stories surrounding the Chernobyl tragedy: a fluid array of narratives, merging into an inextricable web of lives destroyed. The mix of Russian and English passages highlights this polyphony, showing just how complex the events and their aftermath were.

In the final scene, time suddenly seems to stand still. In a heartbreaking performance of the book’s opening monologue, we learn the story of a young pregnant woman, whose husband is among the first to get to the reactor. Receiving hundreds of times the deadly dose, he slowly perishes in hospital, his wife caring for him every day, exposing her unborn child to radiation–for with the radiation dose he’s received, he’s become a nuclear reactor himself. After her partner dies, the woman gives birth–the girl living for just three days. Told from the woman’s point of view–and excellently performed–the story brings home the tragedy of Chernobyl more than all the others, moving the audience to a ghostly silence as the light goes out…

In the brief Q&A after the performance, the main themes of the book were revisited, paying homage to Alexievich’s talent of weaving together pieces of oral history to create her own narrative. D’Jesús’s attention to the intricacies of the book really comes out here, showing just how committed he was to adapting this piece, which would tell the Chernobyl stories of those who have yet to be heard–particularly in the West.

Voices From Chernobyl brings out what happened in all its complexity. It shows that Chernobyl’s effects are living on and are even bigger than the blow it struck to the Soviet regime. It’s an event that touched the lives of huge parts of the Soviet population, but still hardly spoken about. It’s the quiet heroism of the ordinary men and women, willing to sacrifice themselves for a greater cause without rewards or glory. Finally, it puts before us–perhaps more than anything in the cold war era–a population betrayed by a regime that promised salvation.

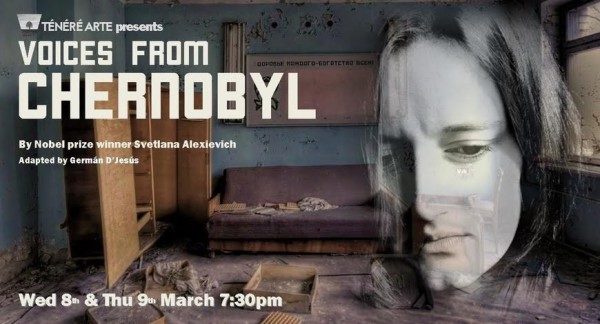

Ténéré Arte’s Voices Of Chernobyl will return for a run at the Jack Studio in May 2017.

This article originally appeared in Central and Eastern European London Review on December 3rd, 2017, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Julia Secklehner.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.