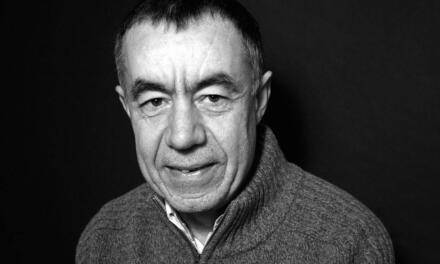

Interview with Mirko Stojkovic dramaturg, video game developer and university teacher about monomyths, nano-spectacles and avatars.

At last years IETM meeting you mentioned that one of the biggest problems of the virtual world is in its lacking emotions. Do you see any way in which we could combat that? It has been said that art can enter this sphere when freedom steps in. Do you know any examples of this?

I was completely wrong. The problem with virtual reality is not a lack of true emotions, but it’s abundance of false ones. A few weeks after IETM I put on Gear VR and found myself on a rooftop in a generic US downtown. A girl was standing in front of me. Sylvan Esso’s “Coffee” started playing, and the girl started dancing.

I’m in my forties and I can’t really remember the last time I was on a rooftop in such filmic scenery with a beautiful girl flirting with me by dancing seductively to a great song. More precisely, I’ve never been in such a situation. That didn’t stop me from feeling emotions which seemed very real from the second the video started. It was like being possessed. There was no introduction, no beginning, no exposition – the sheer physicality of that false world was so compelling that it fooled not only my senses, it fooled my being.

That was the first time I experienced virtual corporeality and it made me feel powerless. For thousands of years people needed stories, myths, plays, or any kind of storytelling to feel what the characters felt. Now, with VR, storytelling suddenly stumbled upon the territory which only music occupied, where form and content are one. That’s the reason, at first, I thought those emotions I felt came primarily from a song, not from a video I watched. But, playing that song without watching a video gave me the memory of that situation, not the memory of watching a VR video. My brain archived it as a real thing.

The form is there and it can produce false emotions by itself. Now it’s up to us to provide the content and the real emotions, born out of having a soul and not from a lack of a visual apparatus to distinguish reality from a stereoscopic 3D image with a frame rate of over 60 per second.

How do you think theatre-makers should use new technologies in order to increase and enhance interactivity from the audience’s side?

Every device on the internet is assigned a unique IP address. Internet protocol version 4, which was conceived at the beginning of the internet as we know it today, limits the number of those devices to 4.293.967.286. It certainly seemed a lot back then, but it was exhausted on 3 February 2011. We didn’t notice it because it was replaced with Internet protocol version 6, which was conceived of at the time the Internet of Things, in which all devices would be connected to each other and we would interact with all of them, was already becoming viable. In order to be on the safe side and not run out of IP addresses in the future again, the creators of IPv6 chose the 128-bit address system. Now we can sleep safely because we can now assign an IP address to every single atom on the surface of the Earth and still have enough addresses left to do another one hundred Earths with their surfaces and their atoms. It does seem somebody’s planning a lot of interactivity for all of us in everyday life. Theatre makers will not have to lead the interactivity race, they will just have to keep the pace with it.

How do you use narrative design in your artistic practice? What is your “procedure” to create?

I teach dramaturgy at the University. Every Tuesday I give lectures first to students in the final year of doctoral studies, then to freshmen students. When I speak with senior students, I insist they should experiment. When I speak with freshmen students, I insist they should obey the rules of the craft.

My procedure is very similar to those Tuesdays: it’s stretched between very strict templates like Joseph Campbell’s monomyth on one side and exploration of uncharted territories on the other. The only time I’m truly satisfied with what I have done is when I manage to mix those two. The most recent example of that mixture is pervasive in the game The Fade Out, an adaptation of James Joyce’s Ulysses, which was played in Belgrade on Bloomsday 2015.

Sometimes the first spark for an idea is an image, another time it could be a single situation I think of, or part of a conversation I overhear. Once I wrote a screenplay without planning anything ahead, I just sat in front of a computer and after thinking for a while about the most interesting combination of a place and a time of day, I typed, “1. ENT. AIRPORT – NIGHT” and started to write. I never repeated that procedure because the finished screenplay turned out to be quite bad, but I guess the present chance to mention it justified its existence in a way. On the other hand, the thing I am directing right now – a documentary TV series about the internet and the way it enriched our lives and endangered our rights – started very cerebral, by deciding which narrative structure to implement in order to be able to do a bit of transmedia storytelling. There’s probably just one general rule I can always vouch for in mine or anyone’s else artistic practice: the subject should be something the artist cares about.

What do you call your artistic practice? Do you have any tag for it?

Nano-spectacle. I used to work in advertising so I know the value of a good name and this one is as good as it gets. But, I did not coin it in order to be branded, I did it with the intention to explain the mechanism behind it. Advertising only helped by inspiring that name through nano-targeting practice, in which our everyday habits, like posting on Facebook or googling, help advertisers to portrait us very precisely. The reason for that intrusion of privacy, which is now happening at a scale never recorded before in history, not even in paranoia-driven totalitarian states like Ceausescu’s Romania or the German Democratic Republic, is a wish of corporations to create ads which will have more of an influence on us.

I’ve read that Oxford Dictionaries’ word of 2016 is “post-truth,” an adjective describing a situation in which objective facts are less influential than appeals to emotion. It took fifty years and one Donald Trump for some people to catch up with Guy Debord’s The Society of Spectacle, the other ingredient of nano-spectacle.

So, my artistic practice – not the stuff I do in different media, just those pervasive games/immersive theatre plays I would make all the time if I could – is based on an intention to make a tailor made a spectacle for one single person. I use a digital footprint of the person who will play the game to fine tune the experience. The goal is to maximize emotional involvement.

How do you imagine performing arts 30 years from now? Do you think that nano-spectacles will be the future?

I’m not sure what they will look like in three years, let alone thirty. I guess some of them will be even more traditional than they are today. It’s a well-known fact that the longest wars in Europe started right after Gutenberg invented the printing press. People suddenly realized how different everybody is, so for the majority the first impulse was very primordial – step back to the safety of your own kind, then try to exterminate all the others, just in case they are a threat. It took Europe a couple of centuries to get over the fact people can be different without being a threat. These days we have the internet, a new kind of printing press, only infinitely more effective, which makes ISIS and this new Cold War feel very unoriginal.

Artists are people like everyone else. The first impulse for some of us might be jumping back in the trenches, which in the performing arts always means going back to classicism, while some of us will head the other way, to the billions of new virtual worlds.

And how do you see the audience, will their role change? If they become more like an active participant, will we even need actors anymore? Or will avatars infiltrate the performing arts?

Their role has already changed, the only question is who is aware of that change. Some didn’t notice the change because they were seeking familiar ground in order to banish a newly found insecurity, and some relished the chance to climb on the stage. I’ve witnessed numerous transformations in pervasive games: very shy and introverted people suddenly become extroverted super spies if the story puts them in that role.

On a much broader scale, we have massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPG). There are thousands of servers which already host hundreds of thousands of avatars which infiltrate the performing arts. On certain types of servers, or game worlds, players are obliged to act like the avatars they chose to be. If they don’t role play, they get banished from that world. World of Warcraft, the best example of that genre, had more than five million subscribers ten years ago and those numbers have grown since. There are numerous games which are similar, with millions and millions of actors, having the whole world as their stage for more than a decade, never stopping, never pausing… That is the Off-Off Broadway of our times. The real change occurs when the audience really jumps in the driving seat. Still, we, the artists, pull all the strings, and even in the games, the branching narrative actually stays very linear. Freedom of choice, like in the real world, is still just an illusion. In the future that could change, but then the audience and the artists will become one and everybody will make art for himself or herself. Nano-spectacle, remember?

Do you think that the new technology tools (AR-VR- pre-programmed Arduino things) has changed the character of interactivity in theatre (compared to the “traditional type” of site-specific performances, like Signa)?

Technology has the ability to change the way we interact but doesn’t have the power to influence the reasons we interact. Good art is always about those reasons and not about those ways, so until the corporations unleash artificial intelligence on us, and the age of algorithm governance commences, the tools will stay just that – the tools.

This article was originally published on Zip-Scene.com. Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ágnes Bakk.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.