Interview with Shule Li: A Chinese Director of Pythonland (2016)

Shule Li is most recently known for directing a Chinese experimental theatre play, Pythonland (2016). He has studied acting at the Central Academy of Drama in China. After finishing a Master’s degree, he worked as an independent theatre director and researcher. From 2012-2016, he has made practice-based research on traditional and experimental contemporary Chinese theatre.

Pythonland (2016) was originally produced in Beijing in 2016. In the play, Shule expressed his understanding of dramaturg in contemporary China. Moreover, he also demonstrated his reflections on the contemporary reconfiguration of traditional Chinese theatre.

The play tells the mythological story of the Chinese Genesis. The play has two parts: Amnesia and Pythonland. The first part tells the story of worldwide rain and blood. In the second part, the Great General of Pythonland becomes allusive while reflecting on his life. (Please refer to Pythonland (2016) of IOTF2019).

Interview:

(The interview was made by Xunnan Li (Author and Artistic Director of IOTF) and Shule Li in Beijing (March 2019) and London (June 2019))

Xunnan Li: It seems that in Pythonland (2016), you have created an organic fusion between the past and the modern. Shall I begin by asking how you understand the configuration of these two stances?

Shule Li: One of the answers to this question is located in how people recognize the concept of the “traditional.” It means that most of the Chinese theatre practitioners recognize the traditional as something rigid or unchangeable. Therefore, they aim to take some advantages over the traditional. In this sense, they perceive the traditional as a total opposite of the contemporary. Hence, we believe that the traditional is the particularly exclusive expression which do not exist in the contemporary.

But in my play, I prefer to see how modern expressions can be linked to the theatrical traditions. In this way, I’m enabled to figure out some connections between the traditional and the contemporary. This is achieved by my previous research on an actor’s body balance in traditional Chinese Theatre.

Based on the research finding, I decided not to use any performance techniques or conventions directly from the traditional theatre. As a result, I created some new gestures and movements onstage according to my understanding of the traditional ones.

XL: Can you explain how did you develop this interest in the connection between the traditional and the contemporary? And how did you set up the focus on the physicality of the actors’ bodies?

SL: To be specific, actors of traditional Chinese theatre create a dynamic balance in the body by shifting their center of gravity. Through applying this idea to my contemporary play, I was able to create Pythonland (2016). What I did was a reconfiguration based on my understanding of the body balance traditions.

Unfortunately, in the past decade, some Chinese directors took for granted that body balance acting would be a new perspective. But, if we research the question in Asian theatres, we will find it not a new perspective but a profound tradition.

It is fine to say I emphasize the physicality of actors’ bodies on stage. But this does not mean that I disregard the literary content of theatre texts. Pythonland (2106), if you have seen it, has a very interesting story.

XL: I appreciate your experiment of destructing the totality of the traditional Chinese theatre in the contemporary context. But it seems that you take a global view of producing the traditional in the contemporary, while the play still looks very Chinese?

SL: I did take a strong global view. However, it was not easy to achieve it in practice. Once you use any ideas from the Chinese tradition, you will be labeled with Chineseness. Even not taking anything directly from the traditional, I found that the play was sometimes put a Chinese nationalism tag.

XL: Well, are you trying to blur the boundary of authenticity or the purity of the Chinese culture or the ‘traditional’ Chinese culture?

SL: No, I definitely oppose it. Technically, Pythonland (2016) was originated in China for Chinese audiences. I was aware most contemporary Chinese audiences have no idea of the traditional Chinese theatre. They might not be able to differentiate my reconfiguration of the traditional from any original expressions. Thus, I would not be surprised if I saw any critics.

XL: How do you assess the current scene of Chinese theatre?

SL: It’s really hard to make an overview assessment of the current situation. We are in a changing era; there are many possibilities we cannot predict. But I’m a bit worried about Chinese theatrical practitioners’ losing their sense of traditional Chinese theatre. I hope contemporary Chinese practitioners pay more attention to exploring tradition.

XL: I learn that Pythonland (2016) is financially supported by the Chinese government. How do you assess the government’s support of innovations on the traditional in China’s theatre market?

SL: I think the Chinese government has established many good funds that give us more freedom to do what we, the artists, want to do. But the financial supports I believe are individual cases.

My team received really friendly and nice supports from the authorities. There were few limits or requirements that accompanied the funding. It was very helpful. Our team and I had great creative freedom.

XL: In your case, how can you get the creative freedom?

SL: As I said, the grants we got are quite pure for artistic development. We are quite lucky, since, as far as I know, some grants require commercial value for the theatre. Sometimes artists have to give up on an idea if it impedes the achievement of commercial value because they have to make their living in today’s society.

To be specific, the funding we got focuses on promoting traditional Chinese culture. Pythonland (2016) fits the target of these funds perfectly because it was based on a reconfiguration of the traditional in the contemporary context.

Second, Pythonland (2016) is also a relatively small production. It requires lower production costs. Therefore, we were better able to create a balance between patronage and the artists’ subjectivity.

Third, the play is also a site-specific one. It was performed in Zhengyi Ci Xilou (正乙祠戏楼), a theatre house that is over 400 years old.

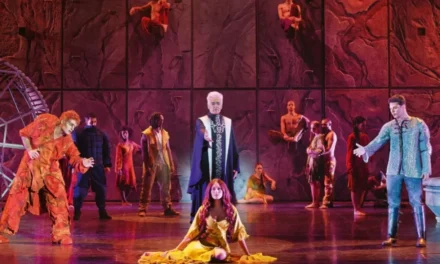

Pythonland (2016). Photo courtesy of the director, Shule Li.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Xunnan Li.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.