Air pollution is recognized as a major threat to human health worldwide. Nine out of ten people breathe polluted air, resulting in 7m premature deaths a year.

While air pollution respects no boundaries and affects almost all of us, it impacts some populations more than others. Deaths attributed to air pollution are ten times more likely in low and middle-income countries compared to high-income countries. Sources of outdoor air pollution include industry, traffic, and agriculture. Sources of indoor air pollution are mostly cooking and heating using solid fuels (including wood and charcoal).

Many people living in urban informal settlements (or slums) are exposed to high levels of indoor and outdoor air pollution. Despite efforts to tackle exposure levels, reductions in air pollution have not been observed. Life in an informal settlement is not easy and there are many daily challenges, of which air pollution is just one. If the choice is between using dirty fuel or not feeding your kids, then is there a choice?

Women cooking in Mukuru.© Dennis Weche, Author provided

Current approaches to reducing exposure to air pollution in informal settlements include awareness raising and campaigns on how to reduce exposure. But these methods have very little input from the people they target. As a result, they may have a low rate of acceptance. Campaigns also generally focus on one source of air pollution, but effective solutions and improvements to health need to take into account all sources of exposure.

And so community-centered approaches are needed to ensure an understanding of the local context and to explore concerns and challenges faced by residents. This will ensure that solutions are culturally relevant, inclusive and therefore more likely to be effective.

Mukuru, Nairobi

This is what we have been doing in Mukuru, which is an informal settlement in Nairobi, Kenya. More than 100,000 families live in crowded conditions with limited access to basic services. Exposure to air pollution can lead to respiratory infection, chronic lung disease, heart disease stroke, and lung cancer. In Mukuru, exposure is continuous due to the burning of rubbish and industrial emissions. The immediate effects reported by residents include burning eyes, sore nasal passages, coughing, and asthma attacks.

Along with a series of interdisciplinary colleagues, we set up the AIR Network so that residents of Mukuru could work together with African and European researchers to explore how best to raise awareness and begin to develop solutions to tackle local air pollution issues. Our creative methods and the involvement of the community allowed us to recognize a series of sources of pollution that we might not have otherwise.

To minimize “Western” and “academic” preconceptions, which can result in a blinkered view, and to maximize engagement, trust, and participation, our network used a variety of creative methods. These included theatre, storytelling, photography and drawing. We were determined from the start to create a democratic and participatory research project so that we could begin to understand the challenges that informal settlement dwellers encounter day to day, with the community deeply involved from the start.

We began with a week-long workshop in Mukuru. For many of us, the creative approaches used were novel and we became a collective, learning together–as well as laughing, eating, sharing, and building trust. Barriers were broken down not just between community and researcher, but also between researchers from different disciplines.

Creating new tools

This is a community that is marginalized, with very few rights or regulations in place to protect them and limited access to basic resources. It is also a youthful community that is hugely self-motivated, bursting with talent, energy, and activism. It is key that the voices of communities such as this are heard. The community educated us on which of the creative methods would work well in Mukuru, and for the next six months, we worked on putting our plans into action.

Our team included talented filmmakers, and we used digital storytelling to document personal experiences of air pollution. Here, for example, Dennis Waweru talks about the impact of air pollution on the health of his community.

Artists from the Mukuru-based Wajuuku Arts Centre painted maps on canvas and took these out into the community so that local residents could use them to identify pollution hotspots and pollution sources. Music was also highlighted as an effective and important communication tool. Local musicians and rappers composed songs to raise awareness about air pollution and the AIR Network itself.

We also used forum theatre (also known as theatre of the oppressed) to develop short plays about key air pollution problems in Mukuru, and then invite local people to become actors and explore potential solutions to the problems presented on stage.

These forum theatre plays were subsequently developed into legislative theatre pieces, which were performed to people in positions of influence or power. Audience members were then also invited to take part in playing out solutions to key air pollution issues, allowing a dialogue to develop between the “ordinary person” and the policy maker, shifting the usual direction of flow and breaking down existing hierarchies.

The real issues

Industry, burning of waste and bad drainage were identified as key sources of air pollution in Mukuru. It turns out that dangerous unregulated working conditions and lack of protective clothing are a major cause of exposure. As is a lack of infrastructure for firefighting, waste disposal (the smoke and smell of burning plastic is constant) and sanitation (sewage was identified by residents as a major source of air pollution).

If we had gone into the community with aims and ambitions that had already been decided according to the commonly acknowledged causes of air pollution (traffic, industry, cooking methods) we may not have had space to reveal or acknowledge these other sources. Instead, we identified issues that the community recognizes as indirect causes of air pollution, such as workers rights, alleyways between dwellings that are too narrow for fire-fighting equipment, and poor waste management.

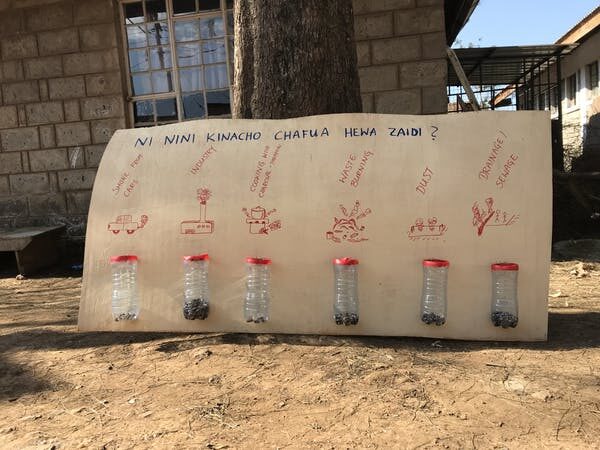

What are the main sources of air pollution? © AIR Network, Author provided

In September 2018, these activities culminated in an arts festival, Hood2Hood, at the local football ground. A stage and a sound system appeared out of nowhere. Forum theatre and storytelling pieces were performed. Rappers, MCs, and dance groups played live. A mural was created. Visual and interactive games were used to collect data. Around 1,500 local people attended the festival during the course of the day, to find out what we had been doing and to make their own contributions to discussions around air pollution.

Wickedly complex global problems such as air pollution, climate change, and antimicrobial resistance can only be properly addressed by using multidisciplinary approaches, real-world actionable strategies and buy-in from the public. Using creativity is key: it allows non-experts to participate more fully in this process so that initiatives and interventions will be culturally relevant and more effective.![]()

This article appeared in The Conversation on March 4, 2019, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Cressida Bowyer.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.