Unstable is the story of an improbable love between a king and possibly one of the lowliest of his subjects. As the executive producer would later say, it is a story of love to be seen in many facets of our life as a nation and as individuals in need of varying degrees of affirmation notwithstanding our imperfections.

Three musical performances set the tone for the evening, one of them by Edaoto being the standout performance in my estimation. The play then commences with a singing group led by the narrator played by Iquo DianaAbasi Eke who delves into a poetical prolog laced with metaphors hinting the audience of what is to come.

The widowed King Ido of the Ozolua kingdom (Played by Bassey Okon), a lonely monarch, thinks aloud about his Prince who is away on a sojourn to conquer the enemies of his father’s land. In what would then appear to be an allegory of the biblical Jesus visited in the temple by a mob of Pharisees seeking the execution of an adulterous woman, the king’s subjects drag Esewi (played by Tina Mba), a woman accused of prostitution before the monarch, urging him to banish her.

Like Christ, the King preserves her life by daring the unblemished among the woman’s accusers to cast the first stone. But while Christ commanded the adulterous woman to “go and sin no more,” King Ido orders Esewi to remain within his court thereby exposing himself to a fatal search for pleasure. The king’s heart is contrived against the virtuous maidens searched out by his chiefs even though they please his eyes. His lips would, however, find sweet words for Esewi and a marriage is soon planned despite the brief opposition of the returning Prince and the sustained revolt of the chiefs.

The beginning of an improbable union between royalty and peasant would, however, signal the gradual decline of the King’s reign highlighted by an excessive show of weakness and indecision even when the new queen is repeatedly found in “sexual situations,” an intriguing euphemism adopted by the palace guard.

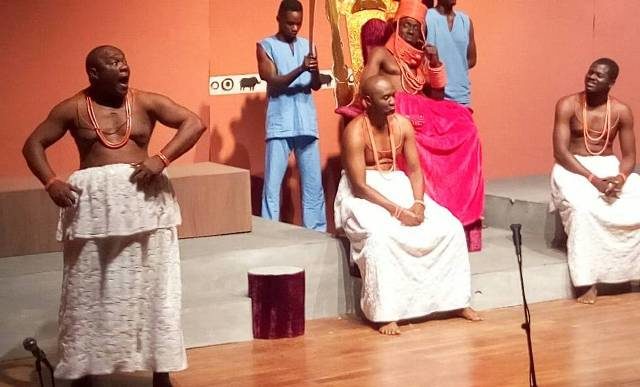

Tina Mba as Queen Esewi and Bassey Okon as King Ido. Photo: Segun Dada

I found the constancy of Esewi’s appeal to the king regardless of her indiscretions and even to other men (including those who joined the mob seeking her banishment), intriguing. In one regard, there is something to be said about the bounds of control in the face of desire and on the other hand is the hypocrisy of those who condemn that which they secretly crave but cannot have. One important lesson, however, is that regardless of the circumstance, beauty may still reside in chaos. Another would be that no human is completely bad as to be undeserving of love.

It is trite that love comes with sacrifice. What is not commonly agreed upon is the extent of reason in determining what to give up in exchange for pleasure. King Ido would, for instance, will his son into temporal slavery in Uzebu kingdom rather than give up the chance to be with the woman who gives him pleasure. When he is, however, tested by the second abduction of his prized possession, he resorts to war, for once showing strength since Esewi appeared on the scene only that it would take just a fleeing survivor of King Ido’s invasion of Uzebu to end his life as he returns to his own kingdom.

The depiction of Esewi as a woman solely motivated by sexual pleasure crumbles upon the death of the king by her side and for her sake. One would have thought she would move on to the next amorous affair waiting somewhere on the horizon but she turns around to give an elegy of the one true love she has had and grabs a sword to pave the path for her eternal sojourn to catch up with that love. This change, sharp and somewhat unconvincing as it is, may have been introduced by the scriptwriter to assert the validity of hope in people and to assert that no one is irredeemably bad. Fair enough.

King Ido (Bassey Okon) calls for war against King Ediae (Ropo Ewenla). Photo: Segun Dada

As it was to me, it may possibly be a surprise to anyone else reading this to find that our exploration of the power and dangers of love thus far has been about a chain of events that never occurred. Indeed, it was all a dream and King Ido startles on his throne to the noise of shuffling feet and accusations as the woman of his dreams is dragged into his courtyard to be judged for adultery. To be clear, that was a nice technique. Obviously not new, yet intriguing in its use.

The play begins where it ends and ends where it begins. We were all spectators to a dream, finding ourselves on the edge of our seat wondering whether King Ido seems same as a warning or the prophecy of an unavoidable fate.

All members of the cast, the play director and producers deserve great commendation for delivering a wonderful performance which is sure bound to help their stated desire to see the theatre embraced by the majority of art-loving Nigerians.

This article was originally published on olisa.tv. Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Tobi Adebowale.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.