At its worst, Altine’s Wrath, written by Femi Osofisan (one of Nigeria’s better-known playwrights) and produced by the Thespian Family Theater, exists solely to pass a message across. At its best, it makes an attempt to provide a window view into a large house and tries to reveal the nature of this complex house using this singular window view.

The result of this is that the most obvious of the issues under examination are over-enacted to the point where they become almost invisible. The themes that end up shining through, do so because they are under-emphasized. Is this downplaying a deliberate strategy? One can’t be certain. For instance, complicity as a theme is present and has the potential to enrich the narrative, but is treated as a sub-sub-topic in Altine’s Wrath. At least once, we see some of the characters in situations where they are aware, have the power to make changes, but do nothing. “The intersection of class and gender is another important theme that struggles to be seen against the larger backdrop of gender inequality.

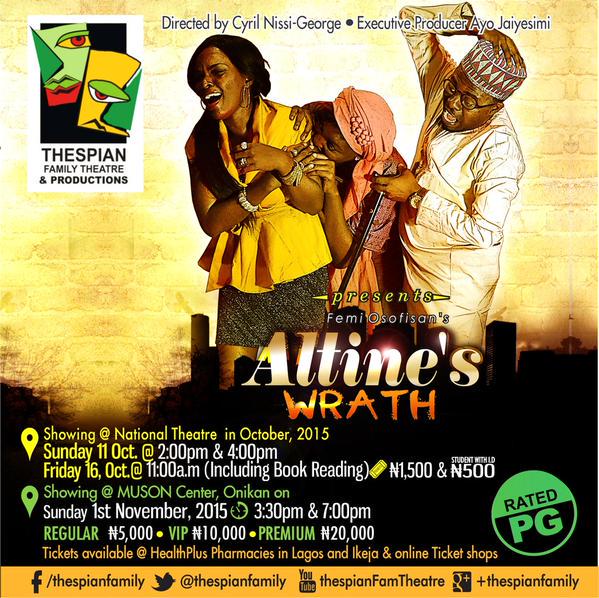

The play opens as an upbeat talk show observing a music break. The point of the talk show scene, we learn in due course, is to interview a very important guest, Dr Aina Jibo (Shaffy Akinrimisi- Bello) who has won a big award for social advocacy. Altine (Zara Udofia-Ejoh), Dr Aina informs the talk show hosts, became a champion for social justice because of her life experiences, and without warning, the scene segues into a documentary on Altine’s life. This jarring transition happens again as the audience begins to warm to the projected screen behind the stage. The documentary ends abruptly and we are simply told that Altine’s story does not end there…

The play opens as an upbeat talk show observing a music break. The point of the talk show scene, we learn in due course, is to interview a very important guest, Dr Aina Jibo (Shaffy Akinrimisi- Bello) who has won a big award for social advocacy. Altine (Zara Udofia-Ejoh), Dr Aina informs the talk show hosts, became a champion for social justice because of her life experiences, and without warning, the scene segues into a documentary on Altine’s life. This jarring transition happens again as the audience begins to warm to the projected screen behind the stage. The documentary ends abruptly and we are simply told that Altine’s story does not end there…

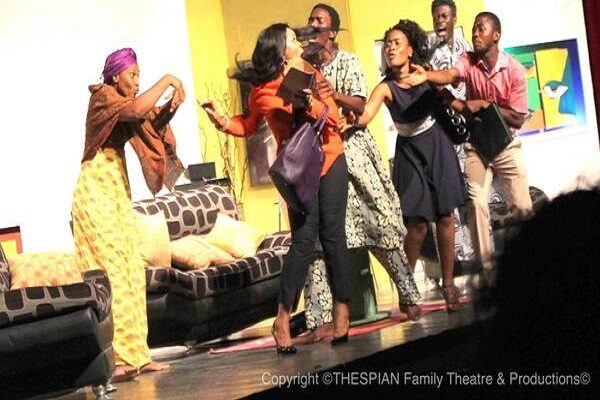

Next, we are thrown into the sitting room of Mr Jatau, Altine’s husband, played by the impressive Abiodun Kassim who we see working himself and his houseboy (named Ahmed and played by Ife Salako) into a frenzy as he awaits the arrival of a certain Alhaji. The whole drama unfolds on the backdrop of this wait for Alhaji. The conversations and transitions move on at a frenetic pace. The door opens frequently, ushering in visitors who move the plot forward. The first of them is Jatau’s mistress (Owumi Ugbeye). Predictably, she is a finicky, entitled sociopath, a cardboard cutout ‘Lagos runs girl’ character. She lacks depth, and for the span of the entire play, the audience gets not a single glimpse into her soul. At one point, encouraged by Jatau to think of Altine as less than an animal, she stands at a distance and says “Shoo, shoo!” to a kneeling Altine. It is perhaps instructive that Owumi Ugbeye’s voice rings hollow in this scene. The moment, meant to highlight Altine’s dehumanization — a fact that has been shown to us a lot and in so many words already — falls flat, underscoring nothing.

That said, there are moments of grace, made all the more powerful by the absence of artifice. These are the moments when the story is allowed to happen. A good example of this is when we see Jatau’s decision to use Altine as his sacrificial lamb for his corrupt deals turn on its head. The dramatic irony comes through clearly because it is allowed to be organic. That scene, in my opinion, is the best argument against the school of thought becoming quite popular in Nollywood circles that insist Nigerians are melodramatic people, a logic which is used to explain the high drama of Nigerian films and plays.

The grand moment is the point at which Altine who has been silent all through, allowing other people: her husband, her husband’s mistress, Dr Aina, and even Ahmed the houseboy speak for her and define her, comes alive and delivers her “listen to my story” monologue. It is quite the moment, marred only by playwright’s (or is it the director’s) decision to define Altine’s unbridling by making her wear the mistress’ clothes.

In the end, outside of the superimposition of contemporary dance scenes — there is a lot of energetic and infectious dancing to Victoria Kamani and Patoranking, during the Talk show commercial break, and the mistress wriggles to Di’Ja while Ahmed tries to grope her — the story follows the pattern of West African classics written between the 60s and the 80s. I could easily have been watching a performance of the Marriage of Anansewa or Sizwe Bansi is Dead, both of which were phenomenal and progressive plays for their time. So while Altine’s Wrath is a funny and praiseworthy attempt at examining very important issues, I maintain that we need a lot of new and ambitious playwrights to talk about the ‘now’ in ways that are fresh and relevant. The theatre scene cannot continue to rely heavily on the continued re-enactments of the classics or on the old story tellers. The occasional new playwright is not enough.

Reposted from Olisa.tv by permission. To read original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kechi Nomu.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.