The African theatre scene in the 1960s and the 70s was mainly peopled by men. But there were women like Efua Sutherland, Ama Ataa Aido and Rose Mbowa that stood shoulder to shoulder with their male counterparts. It is to this crop that Elvania Namukwaya Zirimu, the late Ugandan Playwright and director, belongs. That a soft-spoken girl with a slender build dared to tread a stage dominated by men is already an enigma. Yet those who knew Namukwaya well say that her character was a total mismatch to her body. The late playwright’s surviving younger sister, Ruth Namirembe Olijo, will never forget how during Amin’s regime, in those days of scarcity, Namukwaya threw off a man who was jumping ahead of the queue to take advantage of others. ‘She was naturally funny,’ recalls her sister. Whether it is her good sense of humor, vivacious personality or her stark brilliance that earned her a special place that had been a domain of men, one thing is incontestable: Elvania Namukwaya Zirimu is one of the first-ever and most resonant female voices to emerge in African theatre. Ironically her works are not perennially-studied or often performed like those of her contemporaries.

Early Life

She was born Elvania Namukwaya on 31st August 1938 at Bussi, Busiro, present-day Mpigi District in the central part of Uganda to Mr. Blasio Kyeyune Swaga and Ms. Lusi Namutebi. Her father was a leader of the laity in the Anglican Church of Uganda. He was an emotive preacher, always gesticulating to drive his point home. It was perhaps from her father that Van (as Elvania Namukwaya was fondly called by her close friends and family) picked her acting instincts. But unlike her father who had taken a keen interest in the white man’s religion, Namukwaya harbored a lot of reservations for Christianity. ‘For all the time I lived with her in our father’s house, I never saw Van go to church,’ says Ruth Namirembe.

Given the nature of his pastoral work, Namukwaya’s father moved with his family from one duty station to another. She, therefore, attended several primary schools, including Bussi, Mutetema, and Nsangi. Then in 1953, Namukwaya won a scholarship to King’s College Buddo, a prestigious secondary school in Uganda, then touted as the ‘Eton of Africa’. Here, she excelled not only in the classroom but also in the extra-curricular work such as writing for the school magazine and acting for the dramatic club. She was also the head prefect. Sarah Kyazike Birungi, who met Namukwaya at Buddo and would later work closely with the playwright describes her as well-groomed and almost out of the ordinary. ‘There is a way how she carried herself. You could mistake her for a member of staff.’

Her Reading

In school, she is said to have read voraciously; laying her thumbs on anything that came her way, mostly English classics. When she later joined Makerere University in 1961 and came under the expatriate tutelage of David Cook and Margret MacPherson, her fad for the English canon became inevitable. While at Makerere, Namukwaya met Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Jonathan Kariara, David Rubadiri, John Nagenda and few other writers of her generation. She graduated in 1963 with a Diploma in Education and later crossed seas to the University of Leeds for a Bachelor of Arts in English, finally bagging her degree in 1966, and once again proving she had come to intimate terms with Greek drama, Shakespeare, Brecht and all the white dramatists that loomed her education. But deep in her mental reservoirs, she was exploring a stubborn interest in African folklore and orature. It is a mix of these raw materials, and her spectatorship on the Christian life of her family that Namukwaya would later mash to weave her plays, poems and short stories.

Artistic Output

The 1960s have been referred to as the years of African literary consciousness. The same can be said of the revolution of theatre artists in their attempt to redefine African drama outside the colonial gaze. Somewhere on the east of the continent, Namukwaya was in the vanguard of this movement. She had worked hard in Makerere to brave the strenuous theatrical training demanded by her teachers. She even worked harder to see her play, Keeping up with the Mukasas win the 1962 English Competition, a no-mean feat considering she had to beat male contestants.

When she returned from the UK in 1967, she helped to found the Uganda National Choir. The same year, she formed Ngoma Players. Her play, The Brother’s Wife had just got the first prize in the 1967 Uganda Drama Schools Festival. As one of the first theatre companies in the country, Ngoma Players was self-charged with the mission of reclaiming Ugandan stories from the colonial ethos of the time. The group consisted of Nuwa Sentongo, Milly Aligawesa, Austin Bukenya, David Rubadiri, Pat Howard, among others. A frenzied lot they were. They believed little, if rather anything, in the notions of Western religion. One of their pastimes was to lead processions to unsuspecting friends, drumming and dancing. Once there they would make merry, read poetry and enact or create scenes. It was in out of one of those theatricalities that Van’s last born, Vendo, was initiated, christened by Ssentongo in a rite contrary to the usual Christian baptism. Interestingly, these meetings birthed a very unprecedented academic and artistic brood, and, indeed, several Ngoma players later became university professors and writers of note.

With the Ngoma Players, Namukwaya worked on over 12 of her company’s theatre productions in a myriad of roles, but majorly as a writer, director, and producer. The Family Spear is one of her earliest productions with the company. The play is a searing gender conflict between a woman who labors to fend for a family and a lazy man in a society where the latter is expected to be the head of the family. She followed the Family Spear with When the Hunchback Made Rain (1970) and Snoring Strangers (1973). Gender relations, religion and the conflict of tradition with modernity are the mainly dealt-with subjects in her plays. In When the Hunchback Made Rain, for instance, Namukwaya dramatizes the intricate intersect of man and the supernatural. As a playwright, she had a knack for adapting Western dramatic forms to give practical comment on the African situation.

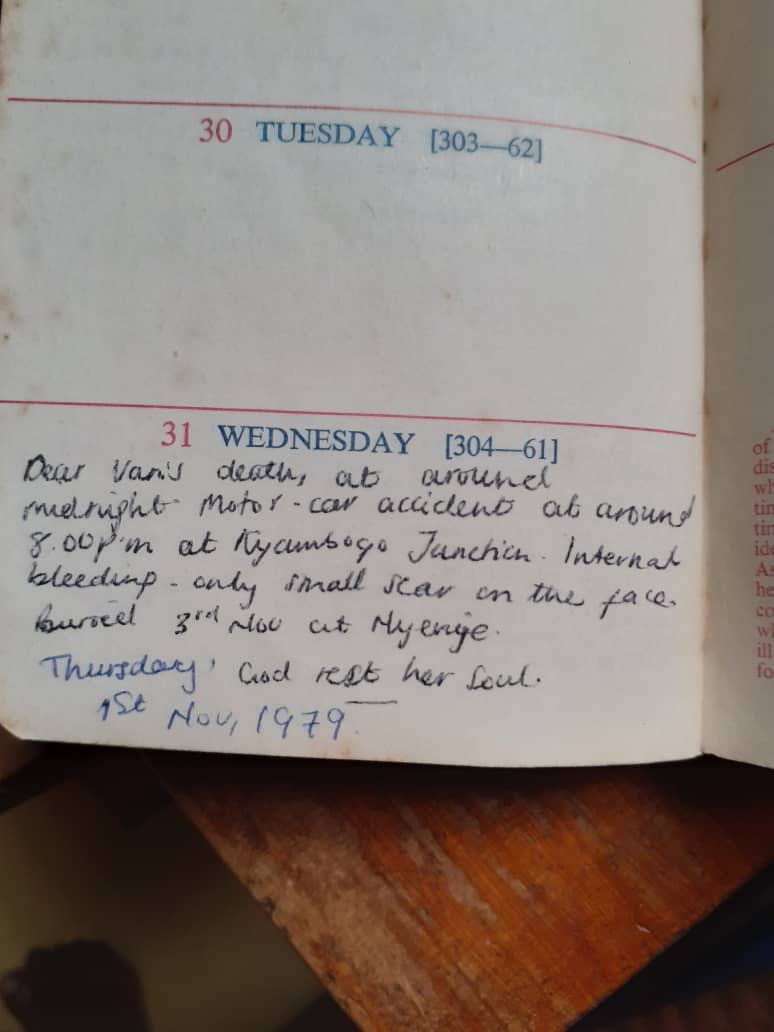

A family member’s journal entry about Elvania Namukwaya’s death. Photos provided and shared with permission from Ms. Elvania Namukwaya’s family.

Other Contribution

Besides her theatrical work, Elvania Namukwaya wore other hats. Between 1967 and 1970, she worked with the national broadcaster, Radio Uganda, thereby lending her magical hand in the production of the first audio dramas in the country. From 1971 to 1979, she divided her time between the National Teachers’ College, Kyambogo where she was a tutor and the National Theatre where she worked as an administrator and artist. The position at the theatre was voluntary and Namukwaya was merely a mwoyo–gwa–Gwanga (working just for the love of one’s country). She is lauded for her active role in the formulation of policy for the Uganda National Cultural Centre under which the National Theatre falls.

In the politically challenging times of Amin, Namukwaya and others ensured that theatre did not go to the dogs as most public institutions had. The dogs came to theatre though, a little later, when Playwright Byron Kawadwa was reportedly picked from the theatre and murdered by state operatives. Namukwaya had just worked as a producer on Kawadwa’s Oluyimba lwa Wakonko, which was Uganda’s official selection for FESTAC ’77, the second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture. Sarah Kyazike Birungi who was part of the cast remembers Namukwaya as strict, professional and dedicated: ‘Rehearsals would start at 5:30 pm, sometimes earlier, and stretch beyond 1:00 am, but Van was always there’.

Outside Uganda, Namukwaya worked with the BBC and the Keskidee Arts Centre in London in the early 70s. Her vision resonated with the Centre’s campaign of breaking ground for black arts in typically white audiences.

Family Life

If you think that for a young woman deeply engrossed in her creative world and work, there was no special place in her heart reserved for a man, you shouldn’t believe yourself. At least not Namukwaya. She had left Makerere with a ring on her finger from Pio Zirimu in 1962. Pio was a distinguished actor and literary scholar. Not long after, they moved together to school in Leeds. The union brought forth two daughters and a son: Julia Nansimbi (born 1964), Lwanga Lutalo (1969) and Vendo Kisakye (1973). Their marital bliss would, however, be nipped in the bud in 1977 when Pio was found dead in bed in Lagos, Nigeria. Pio was part of the Ugandan team in FESTAC. He had just been named director of the colloquium in the festival. The subject of his death is still shrouded in mystery.

Namukwaya’s second marriage was short-lived. This second winner of her heart was fellow playwright Cliff Lubwa p’Chong. They were both teaching at the department of literature and language in Kyambogo and it wasn’t hard to start living together in 1978. Unfortunately, the following year, Namukwaya died.

Last Days

In the interlude between the ouster of Idi Amin in 1979 and the general presidential elections, President Godfrey Lukongwa Binaisa appointed Elvania Namukwaya Zirimu as Uganda’s High Commissioner to Ghana. She was preparing to move in. Accra was calling. And so was the life-sawer! It was the 1st of November 1979. Those were still the days of scarcity. Van and Cliff were returning from getting beers on a black market and had been probably taking a little too much. Van was driving. Cliff was in the co-drivers seat. The road was not the nicest. Suddenly there was a thud. Van was near-death; Cliff survived by a whisker. Ruth Namirembe recorded in her diary (which she keeps up to the present day): ‘Dear Van’s death, at around midnight. Motor-car accident at around 8:00 pm, at Kyambogo Junction. Internal bleeding. An only a small scar on the face.’

Namukwaya was laid to rest on 3rd November 1979 in Nyenje, Mukono. She is remembered by friends and family in many ways. To Sarah, she was a generous friend who got her a plot of land and paid a deposit on her behalf when she did not have the money; to the family, she was the breadwinner who built a house for her parents and paid tuition for her younger siblings. But none of these beats the memory that the theatre fraternity in Uganda and on the continent holds: Elvania Namukwaya Zirimu, the playwright, director, and actress who broke the glass ceiling and shared her artistic finesse with the world.

This article was originally posted at theafricantheatremagazine.com on February 15th, 2020, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ian Kiyingi Muddu.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.