An Iraqi man is using drama therapy to help local drug addicts, juvenile offenders and victims of chemical weapons attacks recover.

The first performance of the play, named I Exist, took place at the hall belonging to the Halabja health department, near Sulaymaniyah. This was particularly appropriate because the northern city was the target of a chemical weapons attack by Saddam Hussein in 1988.

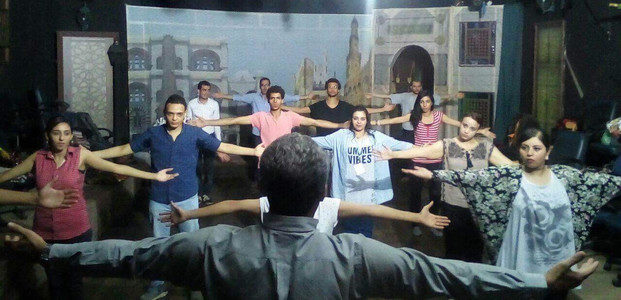

As part of what is known as “drama therapy,” victims of chemical weapons attacks wrote, created, and performed the play and afterward, invited the audience to interact with them.

Drama therapy is relatively new to Iraq. Local man Jabbar Khamat runs what he describes as a “theatre clinic;” basically, he takes the drama therapy practice around Iraq to places where people have suffered some trauma. It is all about reaching different Iraqis in different parts of the country and getting them to interact with one another as well as with audiences.

So far, Khamat has undertaken projects in three different locations. The first was in a borstal, where younger people convicted of crimes were asked to channel their energy into theatre. The second project took place in a clinic for drug addicts and alcoholics, who trained in performance, including vocal exercises and physical therapy. This meant they had to concentrate on something other than their addictions.

The third project was put on for survivors of chemical weapons attacks in Halabja, in northern Iraq. Many of those involved have had breathing difficulties their whole lives and sometimes found it hard to express how just hard that had been, almost 30 years after the attacks.

Drama therapy helps make the amateur actors and playwrights more confident, it helps them concentrate and relax and work through trauma, Khamat explains.

Even though he was invited to the Cairo International Festival for Contemporary and Experimental Theatre this year–Khamat sees that as a sign of his credibility–he admits that it is not an easy thing to convince Iraqis of the merit of drama therapy. There are other challenges too–such as a lack of state funding, the fact that many women from conservative families tend not to get on stage in Iraq and the lack of any premises where he can work regularly.

Still, there are rewards in the performances. In one show seen by NIQASH at a hospital clinic, a drug addict surprised the audience by playing beautiful music on an oud. Although it was not easy for him to face an audience, he was trained in how to use his body and voice.

Music had been his hobby since he was a child, but his addiction had interfered with his musical practice and now the theatre clinic had allowed him to return to it.

This post originally appeared on NIQASH on November 16, 2017, and has been republished with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Sara al-Qaher.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.