In recent years, there has been a growing movement towards promoting and preserving indigenous languages in Kenyan theatre.

Language is usually the first thing that tells a stranger where one is from. For instance, a Kikuyu will gravitate towards Kikuyu art, as will the Luhya, Kamba, and all the other tribes in Kenya.

Before Kenya or any East African countries were colonised, art mostly took place in their mother tongue. During colonialism, Euro-centric theatre was introduced in Kenya, which took place in a box or theatre and was performed in English, the language of the colonial masters. This shift marginalised indigenous languages and led to a loss of cultural identity. It also limited opportunities for audiences to experience performances that truly reflected the essence of Kenya’s cultural diversity. This dominance of English in Kenyan theatre has persisted for years, perpetuating the marginalisation of indigenous languages and cultures in the performance space.

However, there has been a growing movement towards promoting and preserving indigenous languages in Kenyan theatre. This shift aims to reclaim and celebrate the rich cultural heritage of the various tribes through performances in their mother tongues. As a result, audiences are now being treated to a diverse range of theatrical experiences that reflect the true essence of Kenya’s cultural diversity.

Kenya has 44 cultural groupings, each with its own language. However, English and Swahili remain the most common languages of communication.

Swahili is used interchangeably with English and the mother tongue. In my case, I suspect English was my first language , something I can’t say I’m proud of. I later picked up Swahilli, a bit of Sheng and my native Dholuo.

See also: Namulondo Theatre: The Throne of ‘80s Theatre in Uganda

In the Kenyan capital Nairobi, theatre blossomed and would pack to the brim in the 1990s. Plays, especially those that were anti-establishment, were a toast for theatre lovers that soon, the art had become a voice of the people. The shows could run for as long as ten weeks, but amid the fanfare and entertainment, they deepened social and political awareness.

Indigenous Languages in the theatre: The Beginnings

In the 1970s, villagers in Kamiriithu had built a cultural centre to further adult education and the arts by staging traditional plays in their own Kikuyu language. It is here that a number of plays were created.

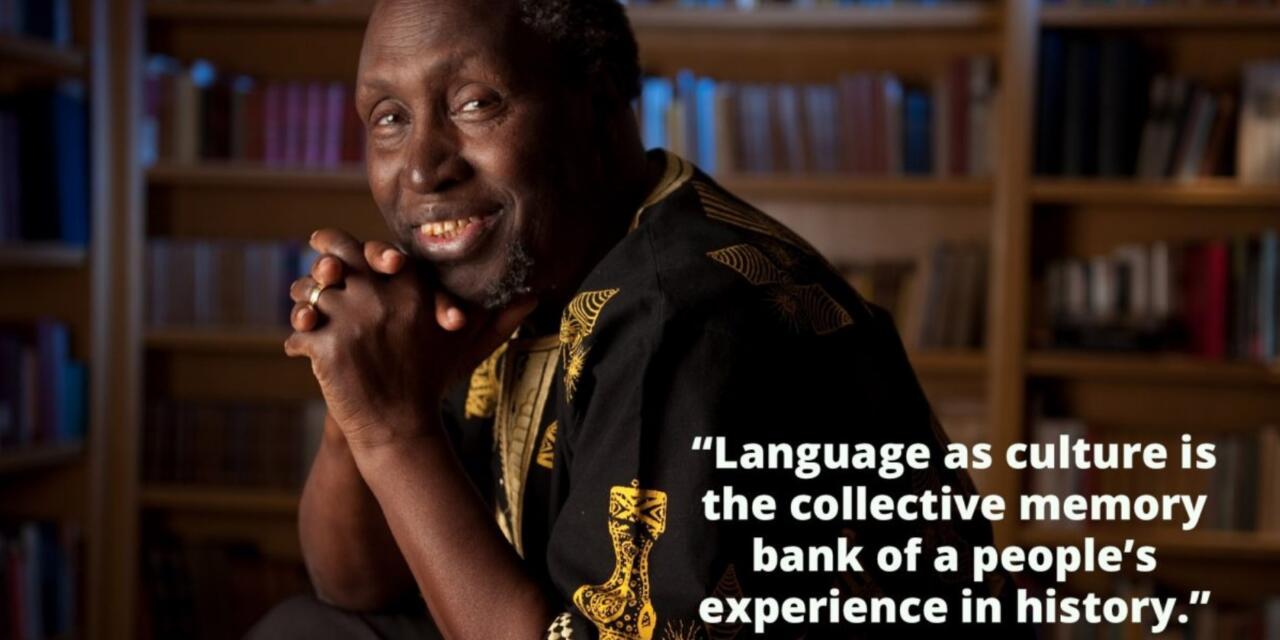

One example of a successful production in an indigenous language is Maitu Njugira by Ngugi wa Thiong’o, which was performed in Kikuyu at the Kamiriithu cultural centre. This play gained popularity for its politically engaged and culturally authentic portrayal of the condition of ordinary Kenyans.

Despite being performed in a local language, it attracted full houses for a month, demonstrating the audience’s interest and engagement. This production challenged the dominance of English in Kenyan theatre and showcased the power of indigenous languages in storytelling and cultural expression.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o‘s plays targeted workers and peasants and were acted by the villagers of Kamiriithu.

Speaking to Inter Press Service, Mbugua wa Kamau, who was in the original cast of the play, says the play was banned and the centre was torn down by the police.

“Authorities forbade future theatrical activities,” he says.

Ngugi was also forced into exile.

For years, one could imagine it was all dead for theatre in indigenous languages.

However, many people have tried to revive this part of the art. The late Wahome Mutahi, popularly known as Whispers, revived the practice of taking plays to the people and would stage Kikuyu plays in bars.

See also: Dr. Julisa Rowe: On Drama, Ministry and Giving Back to the Next Generation

The revival

As the years went on, many other people tried to revive local languages in theatre in Kenya.

Joseph Njoroge Gitau Mitambo alias Tash Mitambo is an actor and director who began his career with Fanaka Arts in 2012. After Babushe Maina observed his fluency in the language and his initiative when collaborating with actors to schedule scenes, he was promoted to assistant director. As they say, the rest is history. Before founding Renegade Ventures, he directed for Fanaka and Johari5, among other companies.

“I grew up in a Nairobi suburb where interacting with people from other tribes was commonplace. I had to teach myself Kikuyu because English and Kiswahili were the two most widely spoken languages. I developed such fluency that parents would want me to open a school where I could teach their kids the same things,” he says.

Mitambo has over the years been a revelation to the Kikuyu theatre and comedy scene; he has penned, directed, and produced a number of productions including Reke Ithambio which ran at Phoenix Theatre in 2021 and recently in August 2023.

As his way of ensuring the continuity of indigenous languages in Kenyan theatre, he has made sure that wherever he is directing or producing, he introduces two actors, both male and female, to the audience.

A particular point of pride for him to date is the fact that almost all the actors he has trained were snapped up as anchors or show hosts for local TV stations.

Then there is Johari5, formed in 2012.

Made up of five actors from Heartstrings Kenya, Johari5 was passionate about telling authentic Kikuyu stories. The target was the Nairobi-bred Kikuyus, those who did not speak the language very well. The dialogue was kept simple and played light; for instance, there was a scene with Kikuyu translating a Rihanna song.

“We had a good run performing almost monthly at the Kenya National Theatre; we went on for three years, but it eventually folded mainly due to financial pressures and life transitions for the members,” says Caroline, one of the members.

Leonard Okware: 39 Years Behind the Lights

Despite the challenges, Johari5’s dedication to sharing authentic Kikuyu stories resonated with the audience and garnered a loyal following. The group’s performances not only entertained but also sparked a sense of cultural pride among Nairobi’s Kikuyu community. However, as financial constraints and personal circumstances took their toll, the once vibrant theatre group sadly had to disband, leaving behind a legacy of artistic expression and cultural preservation.

What about Inclusion?

The Asian community was recognised as one of the 44 Kenyan tribes on July 22, 2017. Unless you are actively involved in the theatre scene or a member of the Indian community, hardly much is known about Indian theatre.

Kunjan Nitin rates himself more as a writer and director than an actor. “Everyone in Kenya does everything; you are a writer, director, producer, singer, and music composer, so I guess I fall into that category as well.”

Nitin, a prominent figure in the Indian theatre community in Kenya, is passionate about showcasing the rich cultural heritage of the Indian community through his work. With a focus on promoting diversity and inclusion, Nitin believes that theatre can serve as a powerful medium to bridge the gap between different communities and foster a sense of unity. As he delves deeper into his journey as a writer and director, Nitin hopes to bring more visibility to Indian theatre and create a platform for artists to express themselves freely.

In 2018, he founded his company, VIGBYOR, and they staged A Shaft of Sunlight, by Abhitaj Joshi. This is a play exploring the conflict that exists in a marriage between a Hindu and a Muslim against the backdrop of the explosive communal politics of India. He made the decision to stage it in English with Hindi music and set it in Kenya in the ‘90s. This was intentional so that anyone could watch the show. They were able to stage the show for close to 2000 people.

The second production was a dark comedy entirely performed in Gujarati.

“I can’t write it, read it, or barely speak it, but I do understand the language. I took the script to the producers and told them I would want to direct,” he says.

Of course, the producers were skeptical of his ability to pull it off, given his limited knowledge of the language and culture. But he constantly sought help from his team.

The show sold out in five shows.

Through Mombasa to Nairobi, indigenous theatre shows have been a breath of fresh air, yet in the same way, they have divided opinion. Because there are things that only people of a particular tribe could address effectively, some people have accused vernacular theatre of promoting sectarianism and tribalism.

In 2014, the topic was raised after Arena Media in Nairobi held the first Luo Festival. The two-day event presented a varied audience with an array of entertainment, such as a fashion show, traditional dances, plays, and luo comedy, among others.

See also: Project Ivelo: A Village, Theatre and Fun

Speaking about the thought of tribalism, Adhiambo Opondo, then the head of operations at Arena Media, noted that the shows are meant to celebrate heritage and culture.

“We want to appreciate our native people, but that doesn’t exclude others. You don’t have to be Luo to attend our productions.”

The question of viability

Paul Ogola, a Kenyan actor known for his notable work in films such as Nairobi Half Life and Kati Kati, along with the Netflix series Sense 8 and Sacred Games (Season Two), says that he began his acting journey on stage with Galaxy Players and Heartstrings Entertainment.

This is where he had the opportunity to do Dhako Ok Sechi, originally a Ray Coone play that was workshopped to fit a Luo narrative.

“Luo plays have to exude some sort of extravagance. They are coming for an experience, so we chose to have a band. To get a Luo band that the crowd idolises, you have to consider the price, which automatically pushes the cost of production up, and maybe that is why there aren’t as many Luo plays here.”

See also: Billy Langa and Mahlatsi Mokgonyana on Pushing the Boundaries of the Craft

The absence of funds has affected the consistency of theatre in indigenous languages even when it is popular whenever it is curated. Across the board, whether it’s producers or actors, the consensus is that the cost of production, no matter the niche you choose, is a constant headache.

Actors can’t realistically quote what they are worth because the producers have to secure a venue for the production to take place. It doesn’t help matters that there are few performance spaces to begin with, so prices are always high and profits are rare occurrences.

But this has not stopped dreamers from making theatre in Kenya’s indigenous languages. Once in a while, be it at the National Theatre in Nairobi or on the streets, you are likely to find a flyer advertising a Dhaluo or Kikuyu play. If all producers of such shows can keep the light on, there is surely an audience. But again, as people, it is important that we take the initiative to introduce ourselves to art in our languages, music, literature, or theatre.

Others have argued that investing in theatre in indigenous languages may not be financially viable considering that English and Swahili remain the most favourable linguas. However, it is important to recognise that promoting indigenous languages in theatre is not about replacing English or Swahili but about celebrating and preserving the cultural diversity of Kenya. By incorporating indigenous languages into theatre, audiences are exposed to a diverse range of theatrical experiences that reflect the true essence of Kenya’s cultural heritage.

Furthermore, the success of productions like Maitu Njugira in the early 1980s and the Luo Festival demonstrates that there is an audience for performances in indigenous languages and that these productions can be commercially successful.

See also: State of the Ape Address Touches on Essential Issues

As a thespian who happens to be fluent in Dholuo, Paul feels that although theatre can be used as a tool to pass on elements of culture, ultimately familiarity with the language has to start at home. “It’s more than just a language; it’s a way of life.”

Language is a major element of culture. The theatre culture in Kenya has for a long time esteemed British theatre as the finest form of theatre. Almost every Kenyan thespian of repute has passed through the Phoenix Players and praises the training and high standards of performance expected, especially during the days of the late director and actor, James Falkland.

However, when you hear of “vernacular” shows, the image that comes to mind is a rather ad hoc execution of the same. Perhaps there is an opportunity to create a method of practice for African theatre that is true to us as a people.

This method would prioritise the incorporation of indigenous languages, storytelling traditions, and local customs. It would be a departure from the Euro-centric model of theatre that has dominated for years and would embrace the diversity and richness of African cultures. Achieving this would require collaboration between theatre practitioners, cultural institutions, and government support.

By investing in the development and promotion of African theatre practices, Kenya can create a vibrant and authentic theatre scene that reflects the true essence of its people.

This article appeared in The African Theatre Magazine on November 4, 2023, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, please click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Sakina Mirichii.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.