You can also read this article in French.

IETM will host its forthcoming Plenary meeting in Porto, Portugal, with a specific focus on Other Centers: new and alternative perspectives and paths in the processes of producing and disseminating the arts. This series reveals how the Portuguese arts sector relates to the topic.

In Portugal, like in many other countries, the general understanding of what cultural participation is—and, consequently, the barriers to it—is limited to the act of visiting or attending. Interest and participation in culture is mainly measured by attendance numbers at museums, monuments, theatres, concerts, and libraries. According to the European Commission’s Eurobarometer 2013 report on cultural access and participation, Portugal is ranked among the lowest across the continent.

Acesso Cultura | Access Culture, where I am the Executive Director, was founded in 2013 as a not-for-profit association aiming to promote physical, social, and intellectual access to cultural programming and venues in Portugal. Its members are culture professionals and organizations, including theatres, museums, performing arts companies, and associations, who seek to fulfill the organization’s mission through training courses, an annual conference, public debates, access audits, consultancies, and studies.

In 2017, with the support of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Access Culture was able to organize one-day meetings with culture professionals in every region of the country and reflect together on our practices and relations with our communities, as well as become more aware of the diverse barriers to cultural participation, on and off-site. In most of those meetings, it was confirmed that the general understanding of barriers to cultural participation is limited to ramps and adapted bathrooms: physical mobility. Our colleagues would also point to barriers such as financial resources and qualified human resources, as well as mentality and lack of specific knowledge on these matters.

The chance to work closely with our colleagues has allowed us to get to know, and in some cases get involved with, a number initiatives being developed that consider the specific needs and interests of communities in different parts of the country, away from urban centers. Promoting access to culture across geographic distance has been a joint effort.

Perhaps the most surprising development—considering the speed with which a number of theatres and companies have embraced the cause—is the adoption of services that make the performing arts accessible for people with disabilities and special needs. There has been a very significant increase in the number of performances that include Portuguese Sign Language, although they are still very much concentrated in Portugal’s two big urban centers, Lisbon and Porto. The São Luiz Municipal Theatre in Lisbon blazed the trail back in 2007, being the first theatrical institution to regularly include Portuguese Sign Language in its productions. The D. Maria II National Theatre in Lisbon followed suit in 2012, and more recently the São João National Theatre in Porto and the Maria Matos Municipal Theatre in Lisbon. Festivals have also joined in, the first being the International Puppet Theatre Festival of Porto (FIMP), which takes place every October.

Audio description was introduced as a resource in mainstream venues in the past three or four years, and demand for it has intensified. Theatres in Portugal are trying to build a relationship with people who are blind and visually impaired and face many barriers to leaving their homes, let alone attending plays and performances. Considering the growing demand, we wish to plan for the future and make sure that we will have enough audio describers available, so Access Culture is launching a training course in April 2018.

Relaxed sessions were introduced in theatres and festivals in Portugal in 2016, although, once again, they are still concentrated in Lisbon and Porto. These sessions are when theatre, dance, music, and cinema take place in a more lenient and friendly atmosphere, where rules regarding movement and noise are less rigid. They may also involve small adjustments to the lighting and sound of a performance in order to better suit different people’s special needs, reducing anxiety levels and making the experience more enjoyable. People with attention deficit disorder, intellectual disabilities, autism, and sensory, social, or communication disabilities, as well as parents with small children, all benefit from these sessions. The above-mentioned two national theatres and Lisbon’s two municipal theatres were the first to embark on this, with two cinema festivals following suit: Doclisboa (in 2107) and MONSTRA–Lisbon Animated Film Festival (in 2018). In April 2018, Cinemas NOS, a big movie theatre chain will be joining in.

In the next few months, with the support of the Millennium BCP Foundation, Access Culture will be presenting a new website that will bring together all accessible cultural programming in Portugal. Its aim is to make the information readily available to audiences, as well as inspire and motivate cultural organizations that are not yet working on access or investing in services that may bring a more diverse audience into their venues.

Access, though, does not only involve audiences but also artists. Representation matters: the work of artists with disabilities needs to be seen widely in order to be accepted as a natural part of programming, rather than an exception. Some young people might not even consider a career in the performing arts if they are not able to enjoy the work of artists with disabilities. Portugal is proud to have two dance companies, Dançando com a Diferença on the island of Madera and Vo’Arte in Lisbon, working with dancers both with and without physical and intellectual disabilities. On top of that, the thirty-year-old theatre company CRINABEL Teatro, based in Lisbon, works with artists with intellectual disabilities. Thanks to these companies paving the way, audiences are now able to see the work of these artists more often, and on mainstream stages, and the artists have also gained recognition abroad.

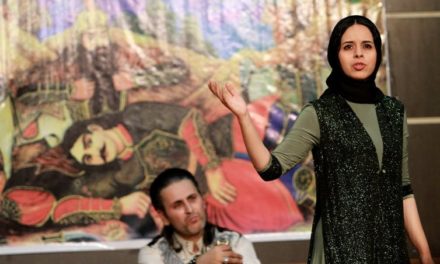

Cultura em Expansão event at Câmara Municipal do Porto (Porto City Hall).

While access to culture is a constitutional right, Portugal does not have a state policy for the promotion of cultural democracy. Consecutive governments have aimed to “democratize access to culture” and the current government is planning to do this with free entry to institutions and digital channels and content.

Culture professionals in many parts of the country go beyond these measures. From the far north to the far south, projects such as Comédias do Minho and Lavrar o Mar aim to develop a more significant relationship with the local communities, as spectators and as artists and co-creators.

One cannot forget that sometimes the so-called “urban centers” have their own peripheries or other centers. One example is Cultura em Expansão, a project promoted by the municipality of Porto with the aim of “placing the cultural offer where it should be: all over the place.”

There are also other organizations that work with a specific focus, like Teatro Griot, the only theatre company in Portugal working mainly, but not exclusively, with black artists; Teatro Praga, which works extensively, but again not exclusively, on gender identity issues; and SAMP–Sociedade Artística Musical dos Pousos, which is responsible for the project Opera in Prison.

At the beginning of this year, Access Culture promoted the creation of an informal working group, called “Central Peripheries,” which brings together individuals who are focused on creating artistic work outside of Portugal’s two main urban centers. During our second meeting, we discussed what moves us and what pushes us to work in this field, and we discovered that people work so that people may have the right to choose their cultural experiences, so that no one decides for them what they can or cannot see and do, so that they do not exclude themselves from certain artistic and cultural expressions before trying them, so that access to and participation in arts and culture become a right they will claim.

It is clear that Portugal’s art professionals are investing their expertise and energy into creating and co-creating a culture that matters, a culture that is relevant, and a culture that acknowledges human diversity, human value, and human needs. Still, there are challenges ahead, like the fact that funding policies and opportunities, for both bigger and smaller cultural organizations, are limited. But the accessibility work is necessary and, in certain cases, especially regarding physical access, there are legal requirements, too. There is also a need to widen our collective thinking regarding cultural participation so that more regions and cities and people may join the movement.

Initiatives are moving at different speeds. They always seem to move faster, though, when access and inclusion are central to the management of a cultural organization and not the concern of just one member of staff. That being said, it is also easier to identify gaps and implement changes or new services when one staff member is responsible for this; when we know who we should be talking to. Things have improved significantly in specific Portuguese cultural organizations. We should learn from them, and create moments and places where experiences, successes, and failures may be shared. There is no need to always try to reinvent the wheel.

Cultural participation is a right. We cannot expect to fulfill our obligations towards the citizens of this country should we keep things to a few mainstream, central arts organizations; should we not acknowledge and support the work that is being undertaken in and with the “peripheries.” Our purpose should be to give people of all backgrounds the opportunity to develop to their full cultural potential, to become active agents in the cultural field, to become more engaged and demanding citizens of this country. Access Culture and a number of cultural managers and artists in Portugal are committed to this and determined to move beyond “democratizing access to culture,” towards a sustained cultural democracy.

This article was originally published on HowlRound on March 29, 2018, and then on IETM. It has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Maria Vlachou.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.