When I reviewed the development season of The Ragged – the first play in what has evolved into THE UNDERTOW quartet – back in 2010, I tagged it “true community theatre.” And it is: of the people, for the people, by the people of Wellington’s south coast, in that its progenitors and leading lights are playwright Helen Pearse-Otene and Te Rākau Theater director Jim Moriarty, who live in Ōwhīro Bay.

By distilling nearly two centuries of Māori-Pākehā relationship into the story of the tangata whenua of Ōwhīro’s fictitious kāinga Te Miti and the visitation upon them of the enterprising settler Samuel Kenning, then following their respective progeny from 1840 (The Ragged), through 1869 (Dog & Bone) and 1917 (Public Works) to ‘the day after tomorrow’ (The Landeaters), Pearse-Otene deftly articulates universal and timeless truths of cultural appropriation and cohabitation.

Book now and then read on, that’s my recommendation. And here is the link to the review of the first pairing in the quartet: The Ragged and Dog & Bone.

Anguished military Patients tell us “I want to go home” and their Nurses call for “healing for all” as we make our ways into Te Papa’s Soundings Theatre. The wooden rowboat that has appeared in both the previous plays is upended upstage to suggest a gothic arch. A soldier lies downstage center, at attention, blindfolded and dead.

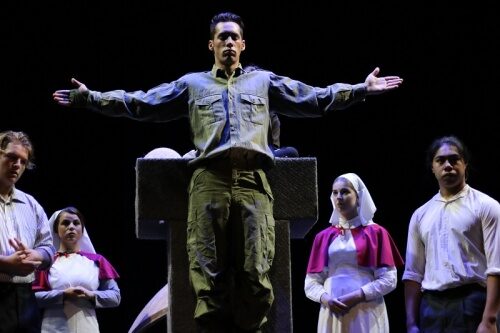

A phalanx of Sparrows – the younger members of the 35-strong cast; a superbly focused and co-ordinated ensemble – whakaeke (enter as warriors in stamping, posture-dancing formation) and surround the body as the Patients and Nurses construct a cruciform tombstone with large grey boxes. The hymn ‘Abide with Me’ is beautifully rendered by the whole cast as the body is elevated: crucified on the memorial.

Thus we are introduced to Will (Wiremu) Meier (Reuben Butler), mentally trapped in the trenches as his Belgian nurse, Fleur (Greer Phillips), tries to orientate him to a more objective reality. His soldier cousin Hamuera Kenning (Manuel Solomon) mentions brothers lost in the mud. Are they still in Passchendaele?

The non-naturalism of the actions and interactions intrigues: there is a mystery here to solve as the subjective realities of this shockingly wasteful world war emerge from Pearse-Otene’s engagingly wrought allusive and elusive script.

The boat brings Will’s mother Bea (Isobel Mebus) into the action and their lively and relatively innocent childhoods are recalled – touching, among other things, on the edict that Māori must not be spoken in public. The irony of Will’s apparent German heritage has only been mentioned briefly and I’d like to know more about how the Meiers fit in with the Kennings and Te Miti (perhaps a family tree program insert?).

The unexpected intrusion of an ebullient a Kiwi hiker, Harry Kenning (Ralph Johnson), out to “hide a few things before I take off,” compounds the intrigue, especially when he takes Hamuera to be “one of those war enthusiast, re-enactment types.”

The five named characters give strong, committed, and very fluent performances. Amid the heartfelt accolades for all involved at every level, special praise is due to Busby Pearse-Otene’s sound design and Lisa Maule’s lighting design, and the way they integrate with the extraordinarily disciplined physicality of the ensemble.

To reveal the crucial truths – about whose imaginings we are privy to, and what exactly has befallen Will – would be a spoiler. But I will go so far as to say Hamuera and Fleur marry and return to New Zealand; to Te Miti and Will’s mother, Bea. And even at this distance from the ‘theatre of war,’ she too proves to be a mental health casualty. Or is she?

The appalling inequity of Pākehā returned servicemen getting resettlement privileges that their Māori ‘brothers in arms’ are denied is dropped in without fanfare, as a simple matter of fact. Binyon’s iconic words from ‘For the Fallen,’ intoned by Harry, leave us to ponder what exactly has been remembered and what has been forgotten.

This story could have been told in a very prosaic, documentary fashion, but Pearse-Otene, Moriarty and the whole Te Rākau company go about it in a far more interesting way, whetting our appetite for the truths and allowing us to discover them; slipping in the political points in ways that will trigger our consciousness and consciences when we are ready to hear them.

Similarly The Landeaters traverses well-trod territory story-wise but does so in a unique way – and this time the political polarities are strongly expressed by the holding-his-ground protagonist Harry Kenning (Ralph Johnson) and property-developer antagonist Wayne Tinkerman (Matthew Dussler), requiring us to evaluate the situation according to our own principles.

Harry is a Vietnam vet, and served in Borneo before that … And here I pause to do the math, wondering how this could be the same Harry Kenning who popped up in Public Works, set a century ago. Perhaps he’s Harry, grandson of Harry. Except the Harry who buried stuff in the earlier plays (back in Te Miti, sometime after WWI) does seem to be the same one who is looking for them now, or rather ‘the day after tomorrow.’ Maybe, since dream-worlds are involved, prescience is permitted. Anyway …

In his own mind, at least, Harry remains fighting fit and has no intention of giving his ancestral home at Te Miti over to Wayne Tinkerman’s bulldozers – or rather the somewhat disaffected subcontractors – to make way for a retirement village. He has ‘gone to ground,’ dramatized as hiding out beneath the 200-year-old willow tree, under which his whenua is buried (presumably planted by the first English arrivals: Samuel Kenning or Borrigan, perhaps). Metaphorically, Harry has gone back to his roots.

In the earlier plays the convention of playing most of the dialogue straight out front, instead of to each other, takes a bit of getting used to, being more redolent of vaudeville than the ‘direct address’ conventions of Elizabethan and Jacobean soliloquies or Restoration asides. But here it works well because most of the conversations are on the phone, so eye-contact is irrelevant.

While the ‘present time’ ‘siege’ scenario sees an angry Wayne fall down a hole to join Harry while Harry’s niece Piri (Kimberley Skipper) observes what’s happening above from her car and updates her uncle by cellphone, other dimensions of Harry’s life are ingeniously integrated into the action.

Talkback radio and remembered sorties into the jungle – including an especially impressive ensemble-created helicopter – evoke the Vietnam War and its toxic aftermath, and inform our understanding of Harry’s current behavior and state of mind. Phone calls from Sam (Nicole Ashton) concerning his application for a Veteran’s Benefit, and from his psychotherapist Lou (Mearn Houston) offer further insights to Harry’s circumstances.

But it’s the interactions between Harry and Wayne, powerfully rendered by Johnson and Dussler, that bring the central linking theme of ‘landeaters’ home because, as mentioned above, both are fully committed to their point of view, thus demanding we interrogate our own positions.

Not that Pearse-Otene keeps them in simplistic opposition; she’s too good a playwright for that. Suddenly Wayne is battling bureaucracy, albeit by phone, on Harry’s behalf. Also he’s shocked at Harry’s joy in playing video war games, and perturbed at their potential social damage. Then there is Harry’s racial intolerance of other cultures migrating to New Zealand and settling here…

The way the complexities of humanity are embraced enriches our experience of the play, as does the way these actors embrace the challenges it presents. And because it pinpoints the human condition so well, there is plenty of humor within the drama.

Those who have seen the previous three plays will be looking for the appearance of the butterfly (that’s all I’m saying) and will be intrigued as to what exactly Harry is so intent on finding, that he buried so long ago. The narrative, thematic, visual and action-based threads that recur throughout the quartet enhance the total experience of THE UNDERTOW even more.

Harry’s final statement on what it is “that kills you” offers a profound insight that leaves us contemplating our own futures and our responsibilities to those around us.

So why is it called THE UNDERTOW? Because even as we strive toward a safe shore, the past pulls us back, tugging at our collective conscience? Because our health, safety, and longevity depend on our recognizing the hard-to-face truths that surge beneath the surface? Any other thoughts are welcome in Comments below.

And here’s more food for thought concerning the name Te Miti: the verb ‘miti’ means to lick up, swallow up, destroy.

Billed as “177 years of history, 28 performances, 35 performers, 100% the Treaty in action,” Te Rākau’s UNDERTOW deserves even more the accolade I gave The Ragged last year: “…a richly textured, insightful, humorous, sobering and energizing gift to Wellington and Aotearoa.”

By John Symthe

This article was originally published on theatrereview.org.nz. Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by John Smythe.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.