As New Zealand has lost two of its longest-running professional theatres in the last seven years, it’s a pleasure to be celebrating the 30th anniversary of another – BATS Theatre in Wellington. The enforced closures of Downstage Theatre (Wellington) in September 2013 and the Fortune Theatre (Dunedin) in May 2018 were shocking blows to New Zealand’s theatre community. Not only did each termination represent a serious loss of New Zealand’s theatrical heritage (Downstage was 49 years old, The Fortune was 44), it was the loss of opportunity for our playwrights, directors, designers, technicians, and actors who relied on these theatres for work. Both theatres ended due to long-standing financial difficulties. For many, their demise seemed to signal a systemic failure of New Zealand’s professional theatre funding model.

In contrast, BATS Theatre appears to be thriving and celebrated its 30th birthday on April 6, 2019, with a grand variety show entitled BATStravaganza at the neighboring Embassy Cinema to a full house of around 500 theatre practitioners and supporters. I was there with my family. My son and I reminisced that he had first attended a BATS show with me as a two-year-old. BATS has been one of the most consistent connections in my four decades of living in Wellington. My experience at BATS pre-dates its reincarnation as a professional theatre in 1989. Before that, it was an amateur theatre, founded by British ex-pats David Austin and Rodney Bane whose names were the basis of its acronym – The Bane Austin Touring Society. Rodney was fond of saying that the name was appropriate because he and David were a bit “batty.” David and Rodney – along with directors John Gilberthorpe and Helene Wong – gave me my start in Wellington theatre, acting and doing backstage work, before I auditioned for the New Zealand Drama School in 1977. In this period BATS moved from being a touring company to taking up the lease of the former Unity Theatre at 1 Kent Terrace. As well as mounting their own productions, BATS sub-leased the theatre to other companies.

In 1988, two young theatre practitioners both named Simon – Simon Bennett and Simon Elson – took the plunge to take over the theatre lease from Bane and Austin and re-invent it as a programmed space for professional theatre co-operatives. The refreshed BATS opened its doors on 1 April 1989 with a production of Christopher Durang’s Baby With The Bathwater, and it is this anniversary being celebrated in 2019. At the time it seemed odd to me that they didn’t change the theatre’s name to mark its new beginning, but the march of time has proven me wrong and the BATS brand has become synonymous with experimental theatrical innovation.

One of the most conspicuous signs of the new leadership in 1989 was the re-location of the entrance to the auditorium. At amateur BATS we entered by a dark, circuitous and inhospitable route emerging at the right-hand side of the seating block. Simon Elson carved a hole straight through the middle of the seating block, making a direct entrance to the stage. Actor/writer/director Emma Kinane was present and described this as “shocking and liberating; a no-turning-back moment.” (Duncum and Rodden, 15) The former corridor leading to the theatre was transformed into snug booths in which one could meet friends over a glass of wine or a snack from a tiny bar. These changes, together with a funky decor, signaled the emergence of BATS as a cool place to hang out and a venue for some of the most original theatre in town.

Following the example of Wellington’s oldest professional theatre Circa, BATS has ensured its long-term survival by working on a co-op model rather than paying Equity wages like Downstage and the Fortune did. This means that each production takes the financial risk, rather than the theatre itself. This often means less money (sometimes no money) for the artists, but it ensures sustainability because the annual box office income, together with a modest grant from Creative New Zealand (New Zealand Arts Council) is always enough to cover the theatre’s overheads. Working within a co-op model for 30 years has served BATS well as a place where small independent companies and playwrights can practice their craft regularly in a low-risk environment, develop new work, experiment with form, and even earn some income. BATS has been a focal point for devised theatre in Wellington and hosts a number of festivals each year including the NZ Fringe Festival, the NZ International Comedy Festival, the Kia Mau Festival of Māori theatre, and Young and Hungry (a youth theatre season of new works). The annual STAB season is a hotly-contested commission for innovative original work that pushes the boundaries of theatre. Many New Zealand playwrights have begun their careers through having their plays staged at BATS before moving on to larger venues. A prime example is Ken Duncum, now one of New Zealand’s most respected senior playwrights and Director of Scriptwriting at Victoria University’s International Institute of Modern Letters. Duncum began his career directing darkly comic scripts he co-wrote with Rebecca Rodden at the pre-professional BATS. When these plays were finally published in 2016, the collection was entitled BATS Plays, and included a series of essays vividly documenting the spirit of the early BATS: “Wellington was dark then – next to nobody lived in the city and by 6 pm there were only stragglers on the rain-blasted streets. The urine-colored streetlights were on but the shops were out, and emptiness consumed block after block.” (Duncum and Rodden 2016, 9) Against this bleak setting was the magic that occurred when the lights faded up on whatever inventive set some industrious company had managed to scrape together for little or no budget. The pre-professional BATS matched the textbook definition of a fleapit. There was always a lethal shambles of timber scraps, half-used paint pots and peeling carpet backstage and in my first show there I was advised never to drink from the “hepatitis mugs.” In the introduction to his play Blue Sky Boys (premiered at the professional BATS in 1990), Duncum wrote: “Bats, Bats, Bats … I loved the scungy old place as much as anyone who’d acted, hammered, sawed, plugged, painted, stayed up till dawn fuelled by Roy’s Burger Bar or otherwise enjoyed their nights there.” (Duncum 2011, 20)

For many years BATS shared the three-story building with Roy’s, a sleazy burger bar, an insurance company, and its landlords, the Royal Antediluvian Order of Buffaloes, whose loud stamping from their grand lodge room above disrupted many a performance. In 2011 BATS was threatened with closure when the aging Buffaloes decided to sell the building, but the theatre was saved when Wellington filmmakers Sir Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh came to the rescue, purchasing the building and initiating a complete refurbishment. The theatre continued to operate in a temporary space in a former bar in Dixon Street. When BATS re-opened in 2014, for the first time it occupied the whole building, had three performance spaces, a full-size bar on the ground floor and its original art deco features had been renovated and subtly enhanced by the filmmakers’ architects. BATS was a fleapit no more, but its creative spirit survived another re-invention into a rather smart, small-scale theatre center.

BATS Theatre, Wellington, 2019. Photo by David O’Donnell

Since 1999 I’ve been teaching at Victoria University of Wellington and have watched successive cohorts of students make the natural progression from creating shows at the university’s Studio 77 to developing careers in every aspect of theatre at BATS. Between 1999 and 2008 I directed six plays at BATS (all New Zealand premieres) and some of those remain among my favorite shows I’ve ever worked on. I still attend performances at BATS almost every week.

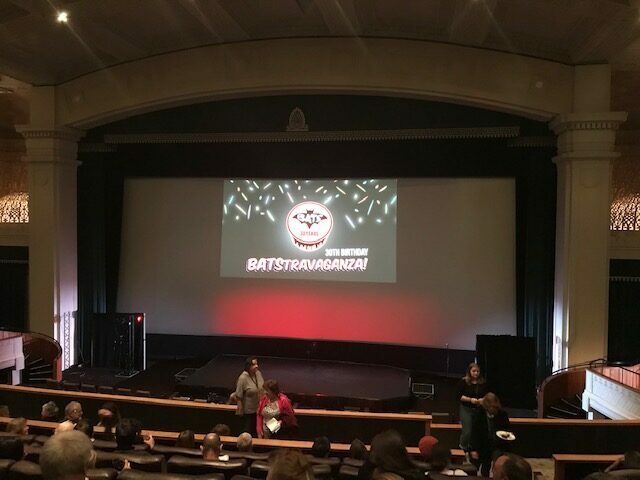

The audience gathers for the BATStravaganza at the Embassy Cinema, Wellington, 6 April 2019. Photo by David O’Donnell

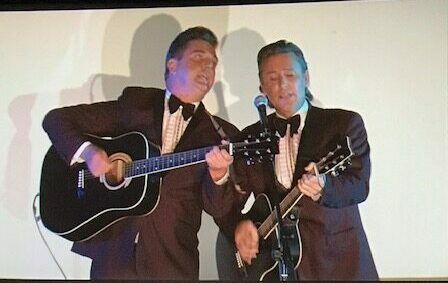

At the posh Embassy Cinema on April 6, BATS supporters gathered early in anticipation of a scramble for the best seats. BATStravanganza was late starting, and the hilariously anarchic co-hosts Jo Randerson and Carrie Green joked that this was in the chaotic spirit of the early BATS. We received a mihi (welcome) in Te Reo Māori from veteran director Rangimoana Taylor, and an introduction from BATS General manager Jonathon Hendry (who ironically was Artistic Director of the Fortune when it closed last year). The performance comprised an eclectic mix of musical items, video tributes, and stand-up comedy, stitched together by Randerson and Green’s improvised MC-ing, featuring many artists who’ve worked at BATS over three decades. Jo Randerson herself has contributed more than her share to the BATS narrative over the years, as a member of the cult ‘90s collective Trouble, with her own company Barbarian Productions, and as a canny mentor to many younger practitioners. My personal BATStravanganza favorites were the extracts from iconic BATS shows which illustrated why the BATS ethos has been so important to our theatre culture in New Zealand. Jacob Rajan performed a piece of his extraordinarily successful solo work Krishnan’s Dairy, in which he deftly intercuts the story of an Indian migrant couple running a corner store with the building of the Taj Mahal. Krishnan’s Dairy premiered at BATS in August 1997 and has gone on to tour the world for 22 years as well as seeding Rajan’s company Indian Ink. The climax of the show was a musical set by Michael Galvin and Tim Balme reprising their roles as Phil and Don Everly (The Everly Brothers) in Ken Duncum’s Blue Sky Boys. This play was an early hit for BATS in 1990, transferring to the 1500 seat St. James Theatre and going on to tour the country. Blue Sky Boys is a tightly woven drama about changing fashions in rock music, based on the fictional scenario that The Everly Brothers played at a broken-down Wellington theatre (i.e. BATS) the same night as the famous Beatles concert at the Town Hall in 1964. Brandishing retro guitars, Galvin and Balme sang some of the Everly’s hits in perfect two-part harmony and had scripted some new banter for the occasion, acknowledging their fictional gig at BATS and the fact that Phil actually died five years ago, creating the perfect climax to the concert before the BATS fans re-grouped and meandered a few doors down to the theatre to continue the celebrations.

For me the most valuable aspect of the BATS birthday was not the performers onstage at the Embassy, it was the conversations, the reunions, the connections, the anecdotes, the storytelling, the sharing of old photos, programmes and posters on social media. All of this illustrated that a theatre is far more than bricks and mortar, it is a memory space filled with imaginative energy, haunted by the spirits of past productions and generations of practitioners who have toiled to make their best theatrical art given the best resources they can gather at the time. The BATS birthday was a celebration of collectivity, creativity, optimism, imagination, generosity, hospitality, hard work, hope and living life to the full, the spirit of theatre itself.

References:

Ken Duncum. Plays 2: London Calling. Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2011.

Ken Duncum and Rebecca Rodden. BATS Plays. Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2016.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by David O'Donnell.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.