The mid-morning phone call I receive from a colleague brings bad news. The Fortune Theatre–the only professional theatre in Dunedin, New Zealand, the only professional theatre in the southern quarter of the country, and the world’s southernmost professional theater–has closed forever effective immediately due to insufficient funds. The theatre is no longer financially sustainable. The fact that it is May 1st, International Workers’ Day, is not lost on me.

The Fortune Theatre’s workers were called to a 9 am meeting with members of the board and told the awful news. They have ninety minutes to clear their desks. It’s over. Messages of shock and sadness fill my Facebook feed. A reporter rings me. Someone suggests fundraising ideas, someone else recalls when a similar thing happened thirty years ago and on that occasion, the Fortune was revived. The fact that the theater has been in operation for 44 years and produced more than 400 shows is a monumental achievement, considering Dunedin’s geographic distance from other New Zealand metropolitan centers, dwindling audiences who prefer to stay at home with Netflix rather than brave a cold Dunedin winter’s night, and tightly constrained arts funding.

The Fortune was founded in 1973 by theater scholar and director David Carnegie, and television producers and directors Murray Hutchinson, Huntly Elliot, and Alex Gilchrist, and staged its first production in 1974. Since 1978, the Fortune’s home has been the former Trinity Methodist Church, a Category 1 listed historic gothic revival building a block from the city center. Like many professional theater companies in New Zealand, the Fortune struggled financially, but its life-story is full of last-minute reprieves, of money being found from somewhere to keep the theater alive, of memorable fundraising enterprises, and of creative personnel, administrators and governing bodies pushing through seemingly impossible odds to keep the theater open. Alas, not this time. The phone keeps ringing; the city’s actors, directors, designers, and backstage workers are in shock. Is it really too late?

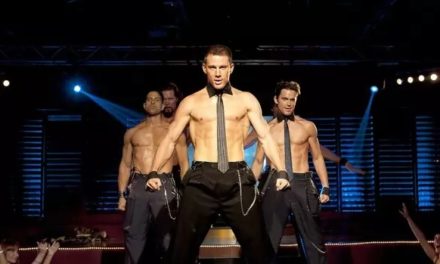

My own career, like that of many theater professionals in New Zealand, began at the Fortune Theatre. In 1984, fresh out of university and aching to be an actor, I was cast by visionary director Tony Taylor as Hermia in his production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Tony had spent a period of sabbatical leave in Germany and had studied the working methods of the Glasgow Citizens Theatre before his tenure at the Fortune. His vivid aesthetic vision and desire for a company structure–rather than the more usual New Zealand model of employing creative personnel on short-term play-by play-contracts–heralded an artistically stimulating period for the theater. He joking called me Hernia during rehearsals. The joke stuck so emphatically that when a fellow actor called my character by her (correct) name, Tony thought he’d made a mistake and stopped the rehearsal to correct him. Later, in 1993 under the artistic directorship of Campbell Thomas, I was in one of the theater’s biggest ever hits, New Zealand playwright Roger Hall’s By Degrees, a play about four “mature” women who go to university for the first time. It was an exhilarating time; the theater extended the season (twice) and put in extra rows of seats, and still, we sold out every night. Yet today my thoughts didn’t remain on those joyful or funny moments.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream by William Shakespeare, Fortune Theatre, directed and designed by Tony Taylor. Photograph courtesy of Fortune Theatre, Dunedin.

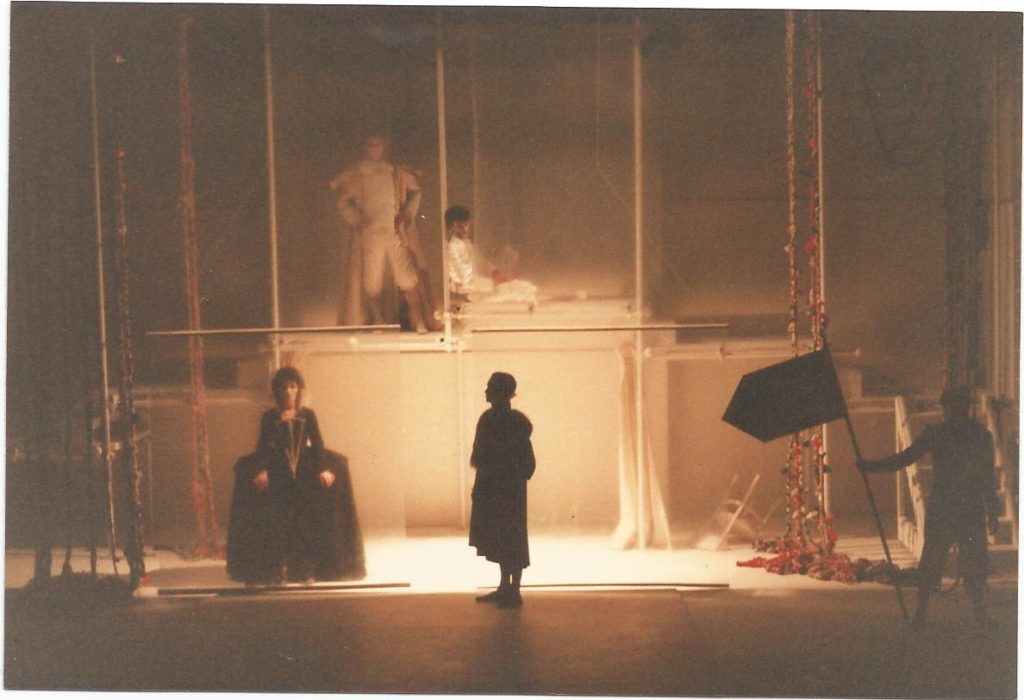

Grief and darkness drew me to recall another performance. In 2012 I was cast in the Fortune’s co-production with the Otago Festival of the Arts of Samuel Beckett’s Play. Directed by Lara Macgregor, the performance was staged not in the Fortune’s building but in a found site, the Standard Insurance Building, a disused building, filled with fallen masonry, cobwebs, grime, dust, peeling and rotting plaster, and–in places–with missing wallboards exposing masonry and the frames of the structure. The site and mise-en-scene echoed the themes of this short work by Beckett. Play runs at around seven-and-a-half minutes’ duration and is written to be performed twice with a five-second blackout between repetitions, meaning the entire piece runs at around fifteen minutes. However, months before we even began rehearsals, an unfortunate piece of misinformation found its way into the publicity material, stating that the performance would be seventy minutes in duration. This meant that we performed Play a total of eight times each evening: four repetitions of the fifteen-minute play with a five-minute “rest” between each repetition. The play’s three characters–a man, his wife, and his mistress–sit in human-sized funereal urns and deliver their text at breakneck speed, each impelled to speak by a blazing theater light. Scholars have asked questions and proposed theories about Play since it was first performed in German in 1963: are the characters alive or dead? Are they in purgatory? What does the light signify?

Play by Samuel Beckett, Fortune Theatre and Otago Festival of the Arts, directed by Lara Macgregor. Photograph courtesy of Fortune Theatre, Dunedin.

Actors Simon O’Connor, Barbara Power and I sat in that freezing cold, dusty, derelict building in our beautifully crafted metal urns, created by New Zealand sculptor Hannah Kidd, which hid our gloves, and the hot-water bottles shoved inside our sweaters. So large and heavy were the urns that we couldn’t get in or out without the help of at least two other people to lift them up. We had made our faces up to resemble the urns, as if we had become part of them from eons of existing in them, stuck. The Light, operated by Macgregor, impelled our speech. It brought us alive; without it, we were disembodied heads protruding from the urns, with our fixed and dilated eyes focused on one spot on the wall. As W1, the wife, my personal point of focus was a barely discernable intersection of walls and ceiling, hanging with creeping dusty cobwebs. Because of the extended duration of the performance, I begin to wonder whether I had inadvertently put myself into an altered state of consciousness, perhaps into a mild dissociative state, which experts tell us can happen if we stare at one spot for too long. That cob-webbed corner became my universe; it was always there and it was always night. I began to wonder if this was reality, and if my “other” life–sunshine, my husband, my garden, our house, family, job, my students, friends, our pets, shopping, movies, plays, the mountains, the beach–were simply illusions, something I had dreamed up because my present condition was too unbearable. What, I wondered was the reality?

Hilary Halba as W1 in Play by Samuel Beckett, Fortune Theatre and Otago Festival of the Arts, directed by Lara Macgregor. Photograph courtesy of Fortune Theatre, Dunedin.

In an effort to explicate the mutable, liminal phenomena and experience of performance, Richard Schechner employs the bifold notion of māyā-lila, where positivist distinctions between reality and non-reality are unable to be sustained (7). John O’Carroll characterizes māyā as “the illusionary world in which we dwell” (322). In that illusory play-world, sitting in that urn, the dream-world became far more “real” than the real world outside. Now that Play-world is like a dream, so was my “real” life, for that brief time, a dream of a dream (Schechner 11); I was like the “Brahmin who dreamed he was an untouchable who dreamed he was a king” and who could not resolve which reality was true (Schechner p. 12 quoting O’Flaherty). O’Carroll poses the question, “can play ‘scoop up’ the real, re-present it to us so that we never see it the same ways again?” (323). Indeed the actor’s experience, the phenomenon, of being constrained, stuck fast in that urn did “unsettle[e] the ‘real’ world” (O’Carroll, 323), providing a bleak antithesis to the “real” physical world.

Today, as I continue to process the news that the Fortune Theatre has closed for good, I feel that same dream-like sense of unreality as I did in that urn, of looking at something far away. “I’m in shock,” says one friend; another writes me a message, “I woke up this morning hoping it had been a dream.” Yet perhaps there is hope. University of Otago Theatre Studies student Sarah Latta organizes a public meeting; more than 50 people attend and the local newspaper notes that “[s]ome theatre supporters branded the shock closure ‘reprehensible’” (Otago Daily Times, 9 May). Fortune Board chairperson Haley van Leewen is quoted in Dunedin’s local daily newspaper as saying the Fortune Theatre “could be the ‘professional theatre in residence’ under a new brand” (Otago Daily Times, 3 May) in a former music venue, Sammy’s, for whose refurbishment as a “performing arts hub” the Dunedin City Council had reportedly “earmarked $5 million in its draft 10-year plan“ (ibid). So it strikes me that the eulogistic tone of my reflections may be inappropriately over-early.

Roger Hall has written a wryly-observed piece about the closing of the theater for The Spinoff, and it, too, strikes an inappropriate tone to those of us still smarting from the closure, but my metaphor of perdition in those Canopic jars may be equally gracelessly placed. Perhaps I should more aptly reference that other play about illusion, the other slippage between the real and the fantastical, my first professional gig at the Fortune, A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Ending in a marriage, albeit a rational–rather than a romantic–one, some kind of provisional equilibrium is reached (and in Tony Taylor’s production the cast all disco-danced to Tina Turner), and perhaps the Dunedin City Council and the out-going Fortune Board, too, will “restore amends.” (Shakespeare, V, i) However, a hui (meeting) of Dunedin professional practitioners on Sunday 13th May gave every indication that professional theatre in Dunedin would rise from the ashes with courage, dedication, and enthusiasm, and that it would be the theatre-makers themselves that would achieve this recovery.

References

Hall, Roger. “’A Sad Day For Dunedin Theatre’: Roger Hall On The Sudden Closure Of The Fortune.” The Spinoff, 2 May 2018. <https://thespinoff.co.nz/society/02-05-2018/a-sad-day-for-dunedin-theatre-roger-hall-on-the-sudden-closure-of-the-fortune/> Accessed 2 May 2018.

Morris, Chris. “Fortune Sees Arts Hub As Its Future.” Otago Daily Times, 3 May 2018, p 1.

O’Carroll, John. “Introduction” to “Ferringhi,” in Gaskell, Ian (ed.). Beyond Ceremony. Suva, Fiji: Institute of Pacific Studies and Pacific Writing Forum, University of the South Pacific, 2001.

Schechner, Richard. “Playing,” Play And Culture, 1(1), 1988, pp. 3-19.

Shakespeare, William. A Midsummer Night’s Dream., New York: Simon and Schuster, 2009.

“Reasons For Fortune Closure Meet Angry Response.” Otago Daily Times, 9 May, 2018.

<https://www.odt.co.nz/news/dunedin/reasons-fortune-closure-meet-angry-response> Accessed 9th May 2018.

“The Closure Of The Fortune Theatre” Court Theatre website.

<https://courttheatre.org.nz/news/the-closure-of-fortune-theatre/> Accessed Tuesday 2nd May 2018.

“Fortune Theatre Shuts Down Today” Channel 39 website.

<http://www.channel39.co.nz/news/fortune-theatre-shuts-down-today> Accessed Tuesday 2nd May 2018.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Hilary Halba.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.