Blake Boyd, Liesel Kopp, Marlene Galan.

Photo by Jeff Lorch.

The latest guest production at Odyssey Theatre in Los Angeles is Grant Woods’ The Things We Do, directed by Elina de Santos. Woods was Arizona’s attorney general in the 90s but his love for the theatre inspired him to write and this is his first play – a middle-aged sex comedy featuring married couples Bill and Alice, and Sara and Ted. “Nothing personal to millennials”, Woods said on an Arizona TV morning show, “but this is not about their little angst problems. It’s more like real problems and real people who have had a little experience.” Ted is a real estate agent who seems to be more stable than Sara, who spends her days drinking champagne, flirting and possibly finding men to have sex with. Bill runs a restaurant while Alice is a yoga instructor who isn’t certain what their marriage means now that their two daughters have left the house and she finds they have nothing in common.

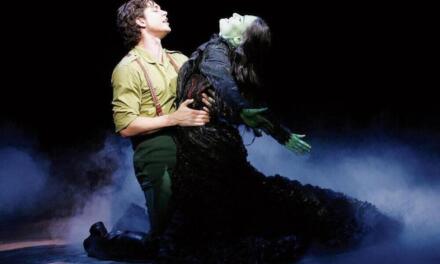

Stephen Rockwell, Blake Boyd, Marlene Galan.

Photo by Jeff Lorch.

Monologues that are given via direct address to the audience are interspersed with scenes between the characters. We open on Bill who tells us that Sara started ‘it’, i.e. their affair. She captures his attention when she mistakes him for a man named Freddie who did ‘that thing’ to her on a night she cannot seem to forget. She brings him home but as they finish their rendezvous, Ted returns and Bill is forced to jump out the window into the pool below. As a cover story, Sara tells Ted that Bill is looking for a home in Malibu and is pleased when Ted thanks her for doing such a good job landing a client. In spite of Bill’s effort to put Sara aside [he tears up her phone number], the two continue sleeping together [he finds all but one digit in the trash and decides to call each of the ‘ten’ [aka, nine] until he finds her].

Liesel Kopp, Blake Boyd,.

Marlene Galan, Stephen Rockwell.

Photo by Jeff Lorch.

Presumably to avoid her feelings of guilt or perhaps to afford them more opportunities to spend time together, Sara suggests that she and Bill should get Ted together with Alice and Bill agrees without a second thought. On this thin premise, the entire play is hung. Alice and Ted hit it off in spite of being polar political opposites. He’s a good listener and wants to know who she is while she’s very self-aware and wants to know the same. All goes well with Ted even promising not to make any moves on Alice until one day he can’t help himself and he tries to kiss her. She’s upset with him, but not upset enough to never see him again. Meanwhile, Bill seems to both tire of Sara and find himself incapable of letting her go while Sara obsesses over his lack of communication when things get intense then seems to easily cut him off like nothing ever happened.

Blake Boyd and Liesel Kopp.

Photo by Jeff Lorch.

As Bill, Blake Boyd seems detached from the reality of his character’s situation. He is able to elicit a laugh when he tries to play it cool at home immediately after his first encounter with Sara but we never get a sense of what matters to him. This is partly due to a text that makes Bill sound prudish if not immature at times – he starts the play by telling us that it ‘wasn’t my fault’ – a potential indicator of his growth as an adult. He agrees far too easily to Sara’s plan to hook Alice and Ted up, especially considering the fact that Sara brings alimony into consideration as if to say, hey, if your wife marries my husband, none of us have to pay! As Sara, Marlene Galan brings the full force of her energy to bear but the character also lacks definition that this production does not try to remedy. We aren’t sure if she really mistakes Bill for this Freddy person – which is an important thing to know – just as we aren’t sure how a woman who can stop a man in a bar to discuss how he nailed her last time could stop short of describing exactly what happened in that encounter in favor of saying ‘that thing you do’.

Every interaction feels very surface, very skin-deep, in spite of the fact that Ted and Alice are essentially crafted to be the deeper, more patient partners of these two. There’s no subtext at work here, no layers to discover, and yes, comedies need that just as much as dramas do [sometimes more]. As Ted, Stephen Rockwell seems to be steadfast in his devotion to Sara but there is no sense of chemistry or history between them. As Alice, Liesel Kopp is the most successful at crafting a fully realized human being in this world but that could be helped along by the fact that hers is the only character in the play that questions its own state of being and seems ready to own their internal thoughts. As the play progresses and Ted does spend more time with Alice, all we get from Bill is a sense of whining complaint as he endures Sara’s attention for reasons that are never considered, let alone played. Do Bill and Sara want to marry each other? Do they want to blow up their marriages? Why do any of this if the answer is no to either? She may be beautiful and he may look like a body-builder but there’s no sense of feeling or desire.

Blake Boyd, Liesel Kopp, Marlene Galan.

Photo by Jeff Lorch.

The direct address can be a tricky thing, and granted I was in a very small matinee house, but it really felt like the actors were directed to include the entire seating area, whether people were in those seats or not. Right after Bill and Sara have sex for the first time the sheet that covers them is quickly deposited on stage under four throw pillows – and remains on stage throughout the play no matter what environment the characters are being asked to inhabit. This is a particularly challenging directorial choice for all of the actors start on stage, no matter when they first speak, and this means that Alice was left in a seated, meditative position just a few feet away from her husband and his lover as they have sex for the first time – right next to the sheet. There was no concrete need to keep Alice there. One might argue there was more reason to keep her out of sight until her first soul-searching monologue that she delivers with her eyes more downcast then they are direct, leaving us to wonder if perhaps she might be struggling to find a narrative thread as much as we are in the audience.

Which brings us back to the text. There are moments throughout where characters share a line of dialogue that resonates and feels like we’ve struck truth instead of gold. For the most part, however, this very much feels like a first play written by someone who didn’t dig too deeply past the first thing they discovered. There are a couple of lame jokes – like when Sara finds a rhyme and says she should turn it into a song and Bill says “I smell Grammy” and she responds “No, that’s just the medicine the doctor gave me to clear things up”, which immediately makes Bill fear that he just contracted a venereal disease. When Bill wonders whether he will be able to pull off ‘nothing’s wrong’ in front of Alice post first sex with Sara he likens that exercise to something akin to a Daniel Day-Lewis Oscar win noting that the stakes are higher – “Ask Mr. Bobbitt”. Sara spends a lot of time singing songs by Cher and Bonnie Raitt and every time she does it, we long for that moment to be over. Oddly, even as those moments drag the overall pacing of the show feels far too fast – in the interest of keeping things moving there never seems to be a moment of peace or breath or recognition. We are rushed through transitions and the scene where Sara first suggests her idea is played out while Bill searches for his clothes – back to her – no connection between the two to justify what they are proposing.

Blake Boyd and Marlene Galan.

Photo by Jeff Lorch.

When Ted inevitably reads Sara’s journal and discovers the affair he tells us -“I didn’t know what to do. A real man would kick her out and end the whole thing. Things are different these days. People have a lot more years in life to live with things. Or without.” That’s a beautiful moment and oh how we wish the entire experience had been built up around it, but it didn’t even have time to resonate. Ted confronts Sara and the two come to terms with his discovery oh so quickly and Ted lets Alice know about the affair without even a moment of hesitation. By the time Bill tells us that he is the kind of guy who is certain men can never be friends with women because they will always be sitting there wishing the woman’s boobs were ‘a little bit bigger”, we are done with him. We have hope for Alice but even she has to characterize her new life of discovery as if she were the ‘loser’ eating alone. Ultimately, conflicts resolve easily, there is no sense of depth to these characters and what we might have hoped would be a funny exploration of sex and love and life after forty ends up feeling less mature than the millennial projects it seemed aimed to outdo.

Produced by Never Dark Productions and Susan Segal. The inventive set is admirably designed by Stephanie Kerley Schwartz. Lighting design is by Brian Gale, Sound design is once again by the talented and omnipresent Christopher Moscatiello. Costume design by Kate Bergh. The Production Stage Manager is Tempest Rockbell.

The production runs through May 12th. For details visit http://www.OdysseyTheatre.com.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Christine Deitner.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.