Studio Azzurro is an Italian group that has been working with different performative languages since the 1980s: video installations, theatre, video art, cinema, interactive installations, interactive museums. In all these artistic experiences Studio Azzurro has never worked using the languages handed down by tradition but has always experimented by mixing them with new technologies. The work they have conducted in the theatre is particular because the use of new technologies has transformed the concept of theatre and has opened the way for the development of new performative forms such as digital or technological theatre. In what follows, we will study the relationship between body and screen in Studio Azzurro’s performances. Analyzing selected performances from the 1980s to the present, we will observe how the body moves and acts when confronted with an on-stage screen, and how in turn the screen reacts to the living presence of the body. The performances we will consider are: Prologo A Diariosegretocontraffatto (1985), La Camera Astratta (1987), Delfi (1990), The Cenci (1997), Galileo (Studi Per L’Inferno) (2006), and Il Coloredeigesti (2013).

Studio Azzurro’s origins and its relationship with video

Studio Azzurro was founded by Fabio Cirifino, Paolo Rosa, and Leonardo Sangiorgi in 1982 in Milan, but its origins and poetics are linked to the 1970s, to the experimentations that arrived in Italy from the US–first, happenings and performances, and then, “the theatre of images,” a term coined by Bonnie Marranca in 1977. 1 In Italy, the interesting research around the theater of images took place mainly in theatre cooperatives and associations born around the time of the student and workers’ movements in 1968. Studio Azzurro’s birth was part of this cultural climate.

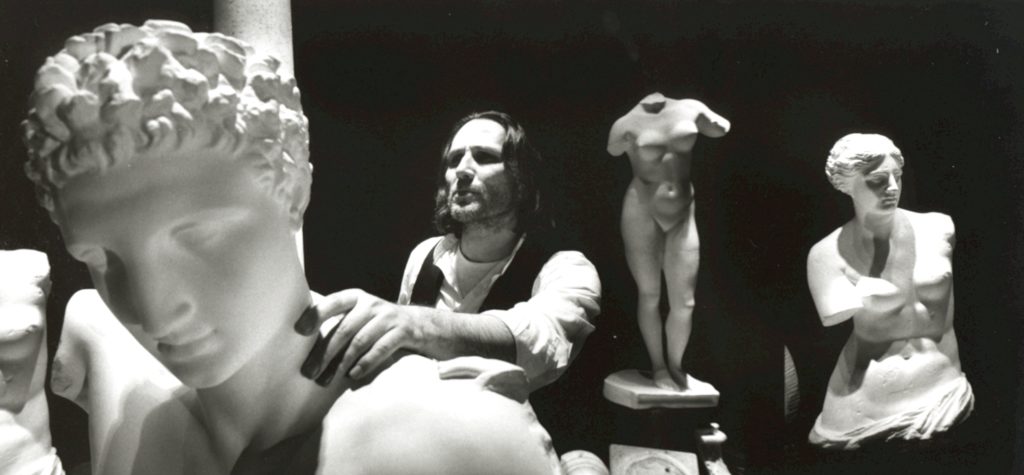

As described by Paolo Rosa: “It begins with the experiments of the 1970s that come before Studio Azzurro: sudden feasts, temporary occupations of places, environmental and “criminal” reconstructions, cinematographic happenings […] At that time, with the experience of the militant communication laboratory, we became aware of the body and gesture, of the actions in the urban space. […] The other root of Studio Azzurro, which we were about to form, was the photographic experience. “2

Studio Azzurro, Photography: Studio Azzurro

Even if at the beginning Studio Azzurro’s work was not properly linked to the theatre, it had all the theatrical elements of the Italian experimentations of the 1970s: the importance of the body, the relationship with the environment, visual elements, the use of new technologies, a minimal dramaturgy.

In the large catalog of Studio Azzurro’s performances, several are termed “theatrical performances,” since they use some theatrical elements and languages. But it is difficult to delineate a line that separates a theatrical performance from a video installation or a sensitive environment since even if there are some differences among them, they belong to a clear and unique poetics.

Although Studio Azzurro’s works use several languages, they are all linked to the new technologies, and specifically to video, since a video is involved in the cultural revolution of the 1960s, and even more so in the 1970s. It is used both in performances and as an autonomous medium–video art. In the 1980s, video and performance are indissoluble. For the Milanese group, the video is “a decompression chamber of a visual stress, it clears and cleans the image and resubmits it as if it were new and never seen.” 3

Performances of the 1980s: Prologo and La Camera Astratta

Prologo and La camera Astratta were realized by Studio Azzurro in collaboration with Giorgio Barberio Corsetti. To analyze them, it is important to know how Barberio Corsetti worked with his actor since they are part of these two performances.

Corsetti is the heir of the Roman experimentation that began with Carmelo Bene. In 1975 he founded his experimental group, La Gaia Scienza in Rome, with an explicit reference to Nietzsche, from whom he gleans the idea of the actor as a philosopher-dancer, stressing his athletic qualities, both physical and mental. For Corsetti, the actor must feel the space that surrounds him like a part of himself and must bring this perception on the scene. Body and thought are no longer two distinct things but a unique act. Corsetti’s actor “freed by function of having to transport characters, feelings and moods […] has imposed himself as full of pure energy, as a physical and psychological expressiveness of his existence in the space.” 4 The encounter between Corsetti’s group and Studio Azzurro’s video installations increased this vision of the actor.

In the first performance, Prologo, 5 Studio Azzurro and Corsetti had decided to link their different experiences, working together with video technologies and theatrical languages and making actors and screens interact in real time. According to Studio Azzurro, it was conceived as a “happy project plan, an affinity that led us to construct in theater an experience not of interference or contamination, as it was common to say at that time, but of perfect symbiosis.” 6

Prologo A Diario Segreto Contraffatto (1985), Photography: Studio Azzurro

The plot of Prologo is hard to describe. The events that are recounted consist of the entries in a traveler’s diary–a traveler of urban landscapes. The traveler is restless, feeling observed and spied upon, and so he reflects on society. According to Valentina Valentini, Prologo can be recounted “as a science fiction history in which some people are imprisoned in a castle guarded by an armed force comprised of electronic technologies. People cannot go out and their freedom is tightly limited to a few gestures and movements.” 7 Only at the end do the prisoners succeed in freeing their bodies and releasing their energy on the scene.

In Prologo and in La Camera Astratta Studio Azzurro uses a particular form of staging, which they call “the dramaturgy of the double set.”

The double set 1, Photography: Studio Azzurro

The space is divided into two parts: one is visible to the spectators, the other is hidden. In the visible part are monitors and the equipment that can enable them to move. In the hidden part are cameras and their operators, who effect the transfer between live recording and the monitors. The performers move between these spaces. As described by Studio Azzurro, “They are the dynamic element that mixes the different natures of the two areas, with their movements and expressions.” 8

When the performers are in the visible portion of the stage, they are physical bodies, real and tangible. When they move into the hidden part, their actions are picked up by cameras and broadcast by monitors in real time. Thus the actors appear to spectators as images–like ghosts, like evanescent and deconstructed bodies–because their bodies are divided and fragmented, as shown in the various monitors.

The monitors move on special structures. The real movements of the monitors have not only a choreographic or aesthetic purpose but also a deep metaphorical meaning and a dramaturgical function. As described by Studio Azzurro: “They must move in the space like actors; they must express themselves like an animated body; they must be able to compare their hyperreal existence with the physicality of the character that acts and reacts instantly to an accident or to the dialogue imposed by the drama.” 9

On the stage, a short circuit is created between the real actor and his image, between body and screen. The continuous rotation of the actors from the visible set to the hidden one overwhelms the spectators’ perception since the two aspects become more and more blended. With the movements of the monitors, the projected bodies can seem more real than the organic ones. Paolo Rosa observes that the monitors “play, move, get tired like actors, reveal themselves in all their physicality and fragility. I don’t know how many monitors ended up exploding on the stage during performances.” 10

The monitor, therefore, is like a human being, like an actor. It has a different purpose from its traditional use. And what happens to the real actor? Comparing himself with his double on the screen, he feels competition; he fights to free himself from his mirror image, to recover his wholeness and uniqueness without falling into narcissism. The video is a transparent surface on which the actor’s body is mirrored or becomes a shadow, risking to disappear, to become engulfed by the screen, because “the actor’s body integrates into itself the surrounding image, giving itself like an image, like a diaphanous body. In turn, to get the integration between electronic and theatrical devices, the actor refuses to use his body directly on the stage.” 11

The relationship between body and screen in Prologo goes through two phases. In the first part, this encounter is dominated by the screen that traps the body and becomes organic. In the second part, the relationship reverses–organic bodies free themselves and explode with all their energy on the stage, “turning from diaphanous bodies to plastic ones.” 12 The relationship between the actors’ bodies and their on-screen images focuses “on the dual nature of the relationship between materiality and immateriality, natural and artificial.” 13 Although the monitor can seem dominant, Prologo works to reduce the conflict between man and machine through mutual compensation and interpenetration. The screens “that restrict free movements of the body are guardian angels that don’t bring death […] but preserve life, storing up energy.” 14

La Camera Astratta 15 is a journey into a mental and timeless space that occurs when a traveler is walking in the open air, and, in a moment of mental suspension, is flooded by memories, images, and feelings. It is a path that allows the body to free itself from memories and problems, and to recover its inner integrity. In this space, thoughts become actions and words, thanks to the integration of body and screen. The body uses technologies to bring out what is inside.

La Camera Astratta (1987), Photography: Studio Azzurro

Compared to Prologo, the machinery of the double set improves, since the monitors become truly like the performers. They appear to detach from the ground and mimic the dynamism of the human body, moving and twirling without gravity. In fact, they are mounted on oscillating machines.

As described by Studio Azzurro, “while Prologo developed along orthogonal lines and monitors were on the ground, La Camera Astratta wanted to develop a dimension suggested by the earlier performance, in which a monitor was suspended in the air like a pendulum. The poetic nucleus of the new performance was born from our desire to develop an airy dimension.” 16

The screen approaches man’s inwardness like a medical device that reveals areas where no one can enter, thus becoming an introspective device.

Delfi (Studio Per Suono, Voce, Video e Buio)

At the beginning of the 1990s, the digital revolution was about to start. In 1991, the World Wide Web was officially born. Mankind was about to be submerged by a myriad of images. At the same time, the TV screen had become a pervasive reality, transforming man’s imagination. In 1990, with Delfi (Studio Per Suono, Voce, Video E Buio) 17 Studio Azzurro protested against pervasive images, hoping to clarify man’s vision.

Delfi (Studio Per Suono, Voce, Video E Buio) (1990), Photography: Studio Azzurro

The tale derives from Ghiamis Ritsos’s poem Delfi. Studio Azzurro’s arrangement is a pseudo-dialogue between two keepers of the museum of Delfi. Only the oldest talks. The younger one, absent from the scene, listens in silence and his words will appear only at the end, on two monitors. The old keeper is tired of showing the ancient remains of Delfi to the tourists that crowd the museum. In fact, their gazes are distracted and wander, as they try to capture images with their cameras. The old keeper dreams that the tourists’ cameras fail, capturing nothing but blackness. From here, the tale begins. In Delfi, narrative and technological levels merge and are essential to each other. The old keeper’s desire to black out cameras is a metaphor for technology.

The stage is dark, everything is hidden from the spectator’s sight, even the actor’s presence. As described by Studio Azzurro: “We imagined two screens linked in live recording to two infrared cameras that would move like eyes. Two pupils, with their synchronized movement, their stereoscopic effect, their ability to create analogies and generate dreams, would guide us to discern a stage full of sculptures, waiting to be given back to a new level of sight, to a new condition of sensitivity.” 18

All elements of the stage can only be seen through the eyes of the technology, shown in all their evanescence through two monitors. In fact, cameras move on the stage to chase and capture the keeper of Delfi as he tries to escape being transformed into a ghostly body. In Delfi, the body does not relate to technology; it does not try to bond with the screen. In Delfi, Studio Azzurro stages essentiality and simplicity against the commercial use of technology, which becomes redundant and contrived as society progresses. It wants poetry to emerge. The denial of sight is the most important element of this performance, and it appears through the verbal text, through the darkness of the stage, as well as through the video technologies that would like to frame what they shoot. As described by Studio Azzurro, “We wanted a purification and a restoration that would separate us from the rush of images, information, and data that were going to attack our imaginations and our behaviors. We felt a sense of tiredness and annoyance that got us close with the words of this tale” 19

In Delfi, Studio Azzurro tries to combat the aggressiveness and superficiality of some kinds of images and the behaviors they arouse.

The Cenci

Delfi, having closed down sight, put the audience in contact with the staging through touch. Touch will be one of the most important elements of Studio Azzurro’s works in the 1990s, together with interactive technologies and the disappearance of the monitors in favor of projections. The closed box of the monitor is retired, and the environment is crowded. In 1996, Paolo Rosa asserted, “These signs, these messages, these figures that mark the new real dimension coexist with simplicity in our daily panorama. They don’t need to be framed by an electronic lens or blocked by a metal television box to be clear.” 20

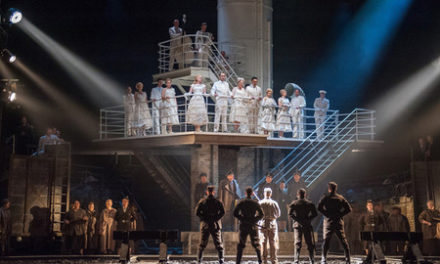

The Cenci is a video musical performance. 21 The narrative text derives from Artaud’s tragedy that recounts the death of Count Francis Cenci at the hands of hitmen working for his wife and daughter. Compared to Artaud’s work, the plot is reduced, focusing on some important scenes like the feast, the murder, the torture, and the sentence. The actors’ actions are combined with Studio Azzurro’s video tales. These videos are divided into 42 micro interactive actions. Artaud considered his tragedy as divided into two narrative levels: the level of narration, and the level of the deeper meaning. In the same way, the video installations have several levels: a descriptive level (creating the locations of the plot), a narrative level (recounting the development of the plot), and a metaphorical level (visually showing the characters’ thoughts and lies).

The Cenci (1997), Photography: Studio Azzurro

The scenery of The Cenci is composed of a big Greek cross, the stage in which the actors move. It has symbolic meaning linked to the plot and represents ecclesiastical power. The cross is not only walkable; it is also a screen for the video projections that extend across its arms, breaking the rectangular shape. Two screens are situated at the end of the two arms of the cross. In the space between the two arms is the orchestra. Video images chase characters and transform the continually changing visual universe. This chase is different compared to that of Delfi, and the relationship between body and screen changes as well, compared to the performances of the 1980s. In Prologo and in La Camera Astratta the screen was the specular double of the actor. Its main trait was transparency, and it could receive and control the organic body. In The Cenci, the screen becomes a projection and suggests a tale, with images. This tale is not cinematographic. Studio Azzurro’s video installations sometimes show only a detail, like the servants’ hands that bring some food to the table. They are no longer the double of the actors, but they redouble verbal and musical stories.

Simultaneous images run with the actors’ words and actions, sometimes linking to them. Other times they contradict them, opening the tale to a new narrative space. They are a visual counterpoint that elevates the text with interpretative jumps and comparisons that induce the audience to look for its own vision before climbing on the cross at the end of the performance. 22

Here, the spectators can interact with the stage and live again the locations and the images of the tale. There is another doubling, not only of the screen in the several projections but also of the actor’s body with the spectator’s one.

In The Cenci, body and screen live in the same space, both telling a story. They sometimes meet when words and images merge, at other times they contradict each other when the screen becomes the character’s mind and shows a different content than that which the actors’ words describe. The screen then becomes layered. More than the actors, who are confined to their roles, the screen represents a multi-temporal condition. Even if the body cannot show all its expressiveness, as in the previous performances, it works with the voice. Battistelli called The Cenci “the theater of music,” 23 because it is not a musical drama, nor musical theater. In fact, even if the real dramaturgy is the music, the text is not sung. The four actors are amplified, becoming sounding bodies, and they use thirty different registers of reciting.

Galileo (Studi per L’Inferno)

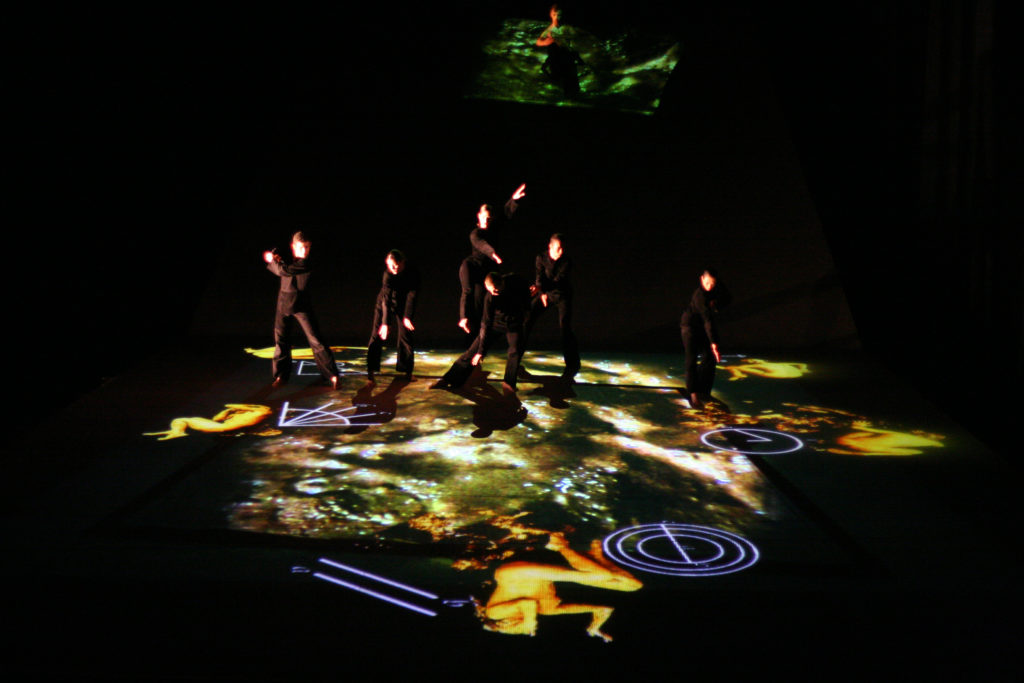

Galileo (Studi Per L’Inferno) is an interactive dance performance. It is not Galileo’s autobiography, but a journey inside some of his theories collected in Due Lezioni All’Accademia Fiorentina, Circa La Figura, Sito E Grandezza Dell’Inferno Di Dante (1588), in which the scientist wanted to measure Dante’s hell with scientific method, 24 With the two lessons, Galileo wanted to link science and poetry, technique and art. This is the reason behind combining interactive technologies and the dancers’ choreographies; it has a metaphorical meaning linked to the plot.

Galileo (Studi Per L’Inferno) (2006), Photography: Studio Azzurro

The stage contains a suspended screen made of Plexiglas, which, exploiting the principle of refraction of the lens that projects images on the stage, creates a duplicate of the images on a plane that slopes toward the audience. A second projector lights up the stage while an infrared camera captures the dancers’ movements through their clothes and turns them into input for the software that manages the projections. In fact, the interactive devices let the dancers modify the scene in real time with their movements, creating an anthropomorphic cosmogony–an organism in constant transformation.

In Galileo, the relationship between body and screen reaches its summit. The bodies and the video projections are the emanations of one another. The dancers are Galileo’s thoughts–the Popes and the measures which, thanks to technology, extend human perception, and succeed in measuring Dante’s hell. The projections are modified by the dancers, as in the scene of the world map, wherein their movements determine the rotation of the globe in all directions to seek the entrance to hell. This is only a part of the body-screen interaction because the opposite also happens. In fact, in some scenes, the dancers must react to the action of the video. In the scene of the mud rain, when a body enters on the stage, it is struck by a virtual squirt of mud that will then form a swamp. The dialogue between body and screen is so deep that it produces a dance between the real body and the body in the video, via the interactive technologies.

Between body and screen, there is no more fear, indifference, or reticence. Digital systems have effected a perfect compensation and indissoluble relationship between them. Finally, there is true dialogue, without the fear that the technology engulfs the organic matter. Both are essential, and they draw strength from their juxtaposition and their dialogue. The body is always on the stage, but now it has extended itself over its physical via technology. The transparent screen has become opaque; it has learned from the body and has become similar to organic matter.

Il colore dei gesti

Il Colore Dei Gesti is a melancholy and poetic performance devoted to Paolo Rosa, expressing sorrow for his death. In 2002, Studio Azzurro created one of its sensitive environments called Meditazioni Mediterraneo, an installation which, as its creators say, “is built around five great “unstable” landscapes that represent in a symbolic way some landmarks of a real itinerary around the senses and places on the Mediterranean. It is the result of journey into a geographical area. The condensation of signs in this area originates in the extraordinary and tormented charm of its territory, but also in the ancient wealth of its cultures and from the mixture of races, religions and customs represented by the people who embrace this mirror of sea.”25

During these journeys, Studio Azzurro filmed craftsmen and people at work in their environment, recording their gestures and sounds, and building a story. Those images composed, as Studio Azzurro says, “a great fresco” 26 that now has emerged after years of collecting the materials.

Il Colore Dei Gesti (2013), Photography: Studio Azzurro

The stage setting is composed of six screens on which the videos are projected, and from which noises and music emanate. On the stage are heaps of colored sand. There is no trace of the performer, who seems to have disappeared. We might ask, has the screen prevailed over the body? No, it has not. The body is always present. There is no performer’s body, but on the screens are the common people doing their jobs, performing their work gestures in natural and evocative environments. Thus the screen is involved as a device of memory–a memory that is not steeped in nostalgia, but in the boldness of the Mediterranean identity.

Notes

1 Marranca, Bonnie. The Theater of Images: Robert Wilson, Richard Foreman, Lee Breuer, Drama Book Specialists, New York, 1977, p. ix-xv.

2 Pittaluga, Noemi and Valentina Valentini. Studio Azzurro TEATRO, Contrasto, Rome, 2012, p. 22. Translated by the author. All the quotes are translated by the author.

3 Valentini, Valentina. Dialoghitra Film Video Televisione, Sellerio, Palermo, 1990, p. 19.

4 Valentini, Valentina. Mondi, Corpi, Materie. Teatri del Secondo Novecento, Bruno Mondadori, Milan, 2007, p. 111.

5 Prologo is a video opera staged for the first time in 1985 in Rome that uses fifteen monitors and seven cameras. The verbal text, written by Giorgio Barberio Corsetti and played by a voice-over, is taken from Of Walking in Ice (1978) written by Werner Herzog.

6 in Valentini, Valentina. Studio Azzurro. Percorsi tra Video, Cinema e Teatro, Electa, Milan, 1995, p. 57.

7 Valentini, Valentina. Teatro in Immagine, vol. 1, Bulzoni, Rome, 1987, p. 184.

8 in Valentini, Valentina. Studio Azzurro. Percorsi tra Video, Cinema e Teatro, op. cit., p. 57.

9 Ibid., p. 56-57.

10 in Di Marino, Bruno. Tracce, sguardi e altri pensieri, Feltrinelli, Milano, 2007, p. 50.

11 Valentini, Valentina. Studio Azzurro, G.B. Corsetti. La Camera Astratta, Ubu Libri, Milan, 1988, p. 18-19.

12 Ibid., p. 18.

13 Monteverdi, Anna Maria. Nuovi Media, Nuovo Teatro. Teorie e Pratiche tra Teatro e Digitalità, Franco Angeli, Milano, 2011, p. 116.

14 Valentini, Valentina. Teatro in Immagine, op. cit., p. 186.

15 La camera astratta is a video opera staged for the first time in 1987 that uses 20 monitors, 13 cameras and 7 actors.

16 Valentini, Valentina. Studio Azzurro, G.B. Corsetti.La Camera Astratta, op. cit., p. 79.

17 Delfi is performed by Moni Ovadia, the old keeper, and the technology equipment is composed of two infrared cameras, two hi8 cameras, one screen, one projector and two monitors.

18 in Valentini, Valentina. Studio Azzurro. Percorsi tra Video, Cinema e Teatro, op. cit., p. 88.

19 in Valentini, Valentina. Studio Azzurro. Percorsi tra Video, Cinema e Teatro, op. cit. p. 87.

20 Valentini, Valentina. Dal Vivo, Graffiti, Roma, 1996, p. 175.

21 The Cenci was made by several artists. Studio Azzurro mainly looked after video installations and interactive systems, Giorgio Battistelli looked after music and, together with Nick Ward, worked to the adaptation of the narrative text. It was directed by Paolo Rosa (Studio Azzurro) and Nick Ward. It was staged on 11 July 1987 at the Almeida theater in London.

22 Studio Azzurro in Pittaluga, Noemi and Valentina Valentini.Studio Azzurro TEATRO, op. cit., p. 129.

23 in Kimberley, Nick. “Cruelty, thy name is Cenci…,” The Independent, 9 July 1997.

24 Galileo (Studi per l’inferno) is a collaboration between Studio Azzurro and The Open House of Nuremberg. It is executed by Daniela Kurz’s dancers, by Studio Azzurro’s interactive and changeable projections, by Andrea Balzola’s dramaturgy and by Tommaso Leddi’s musical compositions.

References

Di Marino, Bruno. Tracce, sguardi e altripensieri. Milan: Feltrinelli, 2007.

Kimberley, Nick. “Cruelty, thy name is Cenci…,” The Independent, 9 July 1997.

Marranca, Bonnie. The Theater of Images: Robert Wilson, Richard Foreman, Lee Breuer. New York: Drama Book Specialists, 1977.

Monteverdi, Anna Maria. Nuovi Media, Nuovo Teatro. Teorie e Pratiche tra Teatro e Digitalità. Milan: Franco Angeli, 2011.

Pittaluga, Noemi and Valentina Valentini. Studio Azzurro TEATRO. Rome: Contrasto, 2012.

Studio Azzurro. Videoambienti, Ambienti Sensibili e Altre Esperienze tra Arte, Cinema, Teatro e Musica. Milan: Feltrinelli, 2007. studioazzurro.com

Valentini, Valentina. Dal Vivo. Rome: Graffiti, 1996.

—. Dialoghi tra Film Video Televisione. Palermo: Sellerio, 1990.

—. Mondi, Corpi, Materie. Teatri del Secondo Novecento. Milan: Bruno Mondadori, 2007.

—. Studio Azzurro, G.B. Corsetti. La Camera Astratta. Milan: Ubu Libri, 1988.

—. Studio Azzurro. Percorsi tra Video, Cinema e Teatro. Milan: Electa, 1995.

—. Teatro in Immagine, vol. 1. Rome: Bulzoni, 1987.

This article originally appeared in Archee and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Vincenzo Sansone.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.