If you’ve never seen an opera before, start here.

If you’ve seen a ton of opera before, re-start here.

The Met’s new production of Matthew Aucoin’s Eurydice with libretto by Sarah Ruhl (based on her 2003 play of the same name) is a fresh, whimsical, and simple love that blends beauty and wit with a singular ease that is as effective as it is unexpected. The opera premiered at LA Opera in 2020, just before the shutdown, and is making its New York premiere here at The Met.

The tragic tale of Orpheus and Eurydice has been the subject of many plays, poems, songs, and operas (Gluck, Peri, Monteverdi). The original tale was known to the Greeks before Homer – and was treated as a historical account rather than a myth. Most renderings of the story, focus on the musician-poet Orpheus, who falls in love with Eurydice, [SPOILERS] loses her on their wedding night, scours the underworld to find her, and attempts to bring her back to the world of the living, only to lose her again at the last moment.

While versions differ in their treatment of Orpheus as hero or trickster, they all trumpet his otherworldly status as the best of all poets whose artistry improves with a descent into grief’s depths; and yet, some versions bear no mention of Eurydice at all; when not left out, she is sometimes unnamed, an afterthought, or conflated with other figures (Persephone usually).

The current Broadway production of Hadestown (Tony-winner for Best Musical in 2019) sets the tale in a bluesy American dystopia, and treats the lovers with nearly equal weight. [By the way: see that, too.]

This rendition of Eurydice is a thing beyond. As the name suggests, this piece, directed by Mary Zimmerman, throws us inside Eurydice (Erin Morley, somehow managing a girl-next-door vibe while delivering a clear, lyric soprano), whose love for artist-husband Orpheus (Joshua Hopkins, a full, vibrant baritone worthy of the venue) clangs against her longing for her underworld-dwelling father (Nathan Berg, whose touching performance manages intimacy and grandeur in a way rarely seen at the opera house).

Eurydice’s wedding festivities drum up the absence of her dead father (“Weddings are for fathers and daughters,” she repeats) while her artist-husband may be drawn away at any moment by his muse (countertenor Jakob Jozef Orlinski, billed as “Orpheus’s Double”). The plot turns around her actions: to follow Hades (playfully devilish Barry Banks) to seek out her father, to re-learn the language of living, and to forcefully forget her grief. The story doesn’t end with her husband’s failed heroics. Instead, we watch this Eurydice navigate three worlds: The world of the living, the world of the dead, and the world of the artist she can never quite reach.

Beyond Eurydice’s love for her father and for Orpheus, the real love story we’re given is that of a playwright’s love of words, of the vibration of names, of the music of language itself. And language is vital in this piece: without language, the characters lose their memories and connections to one another. Words are Life. The most heart-rending moments are those where, dipped in the waters of Styx, underworld characters lose their ability to speak and to remember even their own names. The Three Stones (Stacey Tappan as Little Stone, Ronnita Miller as Big Stone, and Chad Shelton as Loud Stone) serve as comic relief and intermediaries between worlds living and dead.

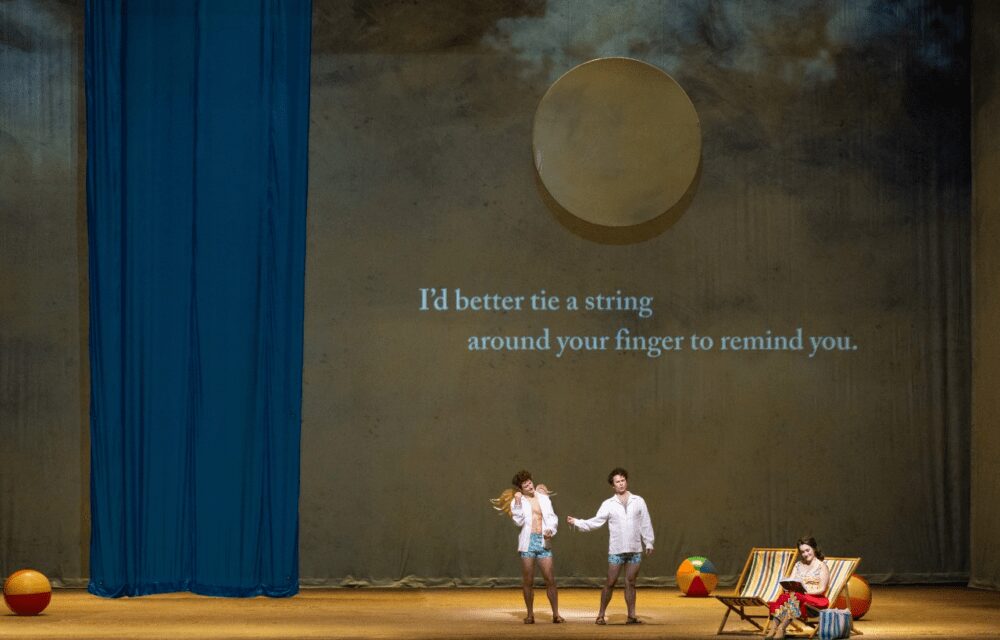

Erin Morley as Eurydice, Joshua Hopkins as Orpheus and Jakub Józef Orliński as Orpheus’s Double in a scene from Act II of Matthew Aucoin’s “Eurydice.” Photo: Marty Sohl / Met Opera.

What’s remarkable about this production, beyond Eurydice’s prevailing perspective, is its perfectly cohesive realization of Ms. Ruhl’s text into music, movement, sets, and costume. Every part of this show originates from and reinforces the simply poignancy of Ms. Ruhl’s words. Despite titles being available on the back of each seat, the English text is projected onto the set to great effect (projections by S. Katy Tucker). We are constantly reminded of the power and music of poetry. Words form and stretch and dance on the walls, emerging as letters are sung out loud, while instruments and voices harmonize and collide. Thankfully, despite the novelty of such projections, legibility and coherence remain intact; it’s just enough visual dynamism to keep your focus on the deliberateness of words arranged in their best order. Likewise, Mr. Aucoin’s score, from the first beat, transports us to an elevated yet accessible world; how else do you describe a fifty-foot curtain pulled back to reveal two giant beach balls, a proposal with a piece of thread, and a muse descending on a swing from the heavens?

Through the addition of Mr. Aucoin’s urgent, driving music, conducted energetically by Yannick Nezet-Seguin, the text finds another dimension along which to stretch and generate greater evocative power. Song wise: We hear Eurydice’s name stretched out syllable by syllable; we hear harmonic Latin text that makes even Stones cry; we hear Orpheus’ lament pointedly checked with Little Stone’s cheeky staccato: “Aren’t you enjoying your grief a little too much?” And for all its stretching, Mr. Aucoin’s music keeps the pace moving as does Ms. Ruhl’s plot. Three acts in under three hours run by fast.

The gorgeous sets by Daniel Ostling buttress the impressive minimalism of the text. Costumes by Ana Kuzmanic, notably those of the Three Stones likewise impress and captivate just as easily as they literally blend into the walls moments later.

In gaining so much through this extensive rendition, the question is: what do we lose by “stretching out” the text to operatic proportions. In my opinion, some of Ms. Ruhl’s witticisms work better with a brevity unafforded by this form. Visual gags and physical humor – such as Eurydice descending to hell with a pink umbrella inside a rainy elevator – come off without issue. I’ve never heard so much laughter at an opera – and this is a tragedy. However some verbal pokes lose their point when sung: “I always thought there would be more interesting people at my wedding” works as a funny aside, but in opera, there are no “asides.”

The loss of the snarky aside is small price to pay for the manifold gems laid out for lovers of the sounds of poetry. The prosody of the English language, various and expansive and generative, makes a rich subject for exploration. Ms. Ruhl’s text is spacious and clean on the page, and it maintains it’s spaciousness even with foot-high letters on the walls. It’s saying something that Ms. Ruhl’s words are spacious enough to fit an entire opera inside, and still leave you wanting more.

Catch this opera where you can.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Fareeda Pyracha Ahmed.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.