Cai Guoqiang is known for his explosive works, but the Chinese artist is now going back to his roots: painting.

Cai, 60, is one of the most successful contemporary Chinese artists in the world and is famous for his iconic firework art, most notably the 29 giant footsteps that marched across the Beijing sky during the opening ceremony of the 2008 Olympic Games. But for his latest exhibition The Spirit Of Painting—which ran for almost six months at the Prado Museum in Madrid—Cai took a more down-to-earth approach.

The exhibition was the first in Cai’s 30-year career to focus solely on painting, though the pieces were still created using gunpowder.

As a child growing up in coastal Fujian province, Cai’s interest was first sparked by his father, an intellectual who ordered Cai to burn his books during the Cultural Revolution. Cai’s father sketched traditional Chinese landscapes onto matchboxes, which were displayed as part of The Spirit Of Painting.

But a rebellious Cai rejected his father’s preferred traditional style, instead studying Western-style oil painting and sculpting from a teacher in his hometown, Quanzhou.

In his early 20s, Cai worked as a set painter for a local theater troupe. He then studied stage design at the Shanghai Theatre Academy for four years before going to Japan to learn about modern art. Cai had already begun creating works with gunpowder in China, where it could be easily bought, but he found himself hamstrung by the country’s strict exhibition rules. In Japan, he got support from a fireworks manufacturer and was able to properly develop his signature explosive art, taking gunpowder off the canvas and into the sky. Eventually, in 1995, he moved to New York City, where he’s still based to this day.

Although the exhibition at the Prado was far away from China, in a sense it was a homecoming. The museum is famous for European classics, and it has a stellar collection of masterpieces by Spanish Renaissance painter El Greco, Cai’s idol. One of the paintings in the exhibition—the first Cai ever created with gunpowder—was dedicated to El Greco. In an article he wrote about himself ahead of the exhibition, Cai explained that he seemed destined to share a similar artistic path with the Spanish painter, as they both moved around constantly before settling down in a foreign country.

Decades on from his first attempt to use explosives, Cai still sometimes struggles to harness their wild power.

“I’ve spent a lot of time studying the technique and craft,” said Cai in an interview with Sixth Tone, adding: “Sometimes I forget how I made [the art] happen.”

Cai Guoqiang (front) prepares his work The Bund Without Us, at the Power Station of Art in Shanghai, July 24, 2014. Wang Rongjiang/VCG

Keeping the childlike attitude toward creating art is important to Cai. In a one-hour documentary by Spanish film director Isabel Coixet, which captures Cai’s creative process during his The Spirit Of Painting exhibition, the image of a little boy is a constant motif. And in the preface of a photobook about the exhibition, Cai wrote that he hoped the book could be a present for the naughty boys who paint.

“I am touched by the primitive and simple feelings of humankind,” said Cai.

After the China premiere during the Shanghai International Film & TV Festival in June, Cai talked to Sixth Tone about why he uses gunpowder and fireworks, and how he balances government restrictions with free expression. The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Sixth Tone: In this exhibition at the Prado Museum, you showcased your paintings instead of your installations or outdoor explosions. What prompted the change?

Cai Guoqiang: I’ve never stopped painting. Artists all begin with a dream to be a painter. When I make installations or social projects, I feel a sense of pity and wonder if I should even persist with my childhood dream.

It is not easy to be a painter these days, as painting doesn’t have the practical function of recording human history anymore. My exhibition is called The Spirit Of Painting, and it’s in search of this spirit.

Sixth Tone: Other artists paint on canvas, but most of the time you opt to use unconventional materials like gunpowder and fireworks. Why do you choose these materials?

Cai Guoqiang: These materials can create and destroy, but they’re difficult to use. On the one hand, I hope to release their energy, but on the other, if I’m only releasing them, I’m not fulfilling many of my aesthetic requirements.

I need to plan an explosion so I can control it. But if my involvement goes too far, I’ll feel that I haven’t made the most of the gunpowder. This process is unnerving but also makes me happy. I am constantly trapped in a cycle of complications, which is actually nice for creation. Artists all create best when they’re anxious and restless.

Remembrance, the second chapter of Cai Guoqiang’s artwork Elegy, over the Huangpu River during his Ninth Wave art exhibition in Shanghai, August 8, 2014. Yi Chen/VCG

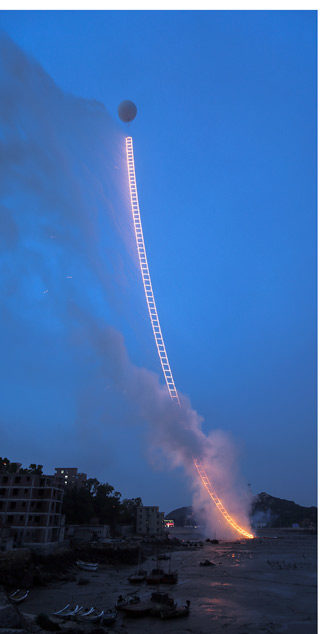

Sixth Tone: There are recurring themes in your works, such as aliens and the sky. For example, your work Sky Ladder stretches from earth to the heavens, trying to connect secular and celestial realms. Is there a special reason for this?

Cai Guoqiang: Everyone’s interested in this kind of thing during childhood; it’s just that I’ve continued with it up until now. I’m curious about the starry night and invisible powers, especially when we have so many real-world problems to face and solve in our hectic daily lives. I often get frustrated in life, but there’s a larger universe in my mind—my art involves interacting with that invisible power.

Sixth Tone: Your hometown is known for its blend of various religions—Buddhism, Islam, Christianity, and folk culture beliefs. You mentioned “invisible power.” Does this have something to do with your own religion?

Cai Guoqiang: When I was young, I converted to Christianity. But now, I mostly believe in traditional Chinese Buddhism, Confucianism, and ancestral worship.

I often explore the theme of the cosmos. I have friends who also explore the cosmos, but they are scientists and philosophers. Their cosmos is the solar system, the galaxy, the Big Bang, and dark matter. Mine goes beyond the scientific universe—it incorporates feng shui, qi, energy channels around your body, and the Chinese zodiac.

Sixth Tone: Many of your works are born out of a collaboration with or commission from governments. How do you see your cooperation with the authorities?

Cai Guoqiang: Collaboration projects with governments are never easy, natural, or free. That’s true in China and in any other country. But sometimes, artists intentionally seek cooperation with the powers that be. Some are in it for fame, others just want a challenge.

Sky Ladder, Cai Guoqiang’s project in Quanzhou, Fujian province, June 15, 2015. Zhang Jiuqiang/VCG

For me, I have a responsibility to show the whole world that China can do wonderful things and that Chinese people are amazing. When I’m doing this, I’m in my natural state. I am like a moth to a flame; I know what I need to do to make a difference.

In the documentary Sky Ladder, I was told that I was dancing in shackles. The authorities were willing to support and help me, but I had to understand and abide by their rules. Creation itself is too easy for artists — it’s nice if we embrace the challenge and create artwork with a sense of tragedy.

I’m not political; I mainly convey my individual perspective.

Sixth Tone: But you also have a lot of works that are about bigger issues.

Cai Guoqiang: Yes, for example, Peasant Da Vincis [a collection of inventions by Chinese farmers]. I seldom do exhibitions hoping to transform society. The project for the Beijing Olympic Games wasn’t intended to affect everyone around the world. Of course, its end result is that it left a mark.

Art isn’t about solving social problems—it’s about solving personal problems. Only after I’ve solved my own problems can I hope to settle the world’s problems.

The most important thing about art is personal style. I’m personally opposed to the idea of political correctness. I am now relatively cautious about trying to influence higher causes like world peace, environmental protection, or cultural diversity.

Sixth Tone: What do you think about those who say that all Chinese modern art stems from the West?

Cai Guoqiang: I disagree. Take installation art for example. We’d already been making it back in the 1980s. The key is how we present the issues of our current time in our own language.

The West has its failures. After 9/11, there haven’t been any powerful and influential art pieces that reflect its own problems. We too have our own regrets. Our economic development and the transition from old to new could give birth to something extraordinary. But we haven’t done that. This is what matters—not discussions over whether or not we’re falling behind the West.

Editor: Julia Hollingsworth

This article first appeared in Sixth Tone on August 6, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Yin Yijun.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.