Sferisterio of Macerata. July 20th 2018

Mozart’s Magic Flute is one of the most famous and well-known works of the Salzburg composer. What can a director do, when tackling this work for the umpteenth time in 2018?

We know that a representation faithful to the text satisfies a large chunk of the audience, but causes another part of the audience to get bored. On the other hand, we also know the tendency that many contemporary directors have taken in the famous “modern staging”–a total distortion of the scenography, of the costumes, some hidden meaning–a part of the audience that appreciates the novelty, another part of the audience that believes that the directors ruin the classical repertoire.

These novelties may be more a provocation than a real artistic research.

We wonder: who is right? Many of those that saw The Magic Flute on Sferisterio from Macerata wondered: how much can a director distort an opera? When we entered the marvelous Macerata’s Sferisterio, we realized that the performance had already started, a sort of prologue of the opera, already accompanying the entrance of the spectators to the theater.

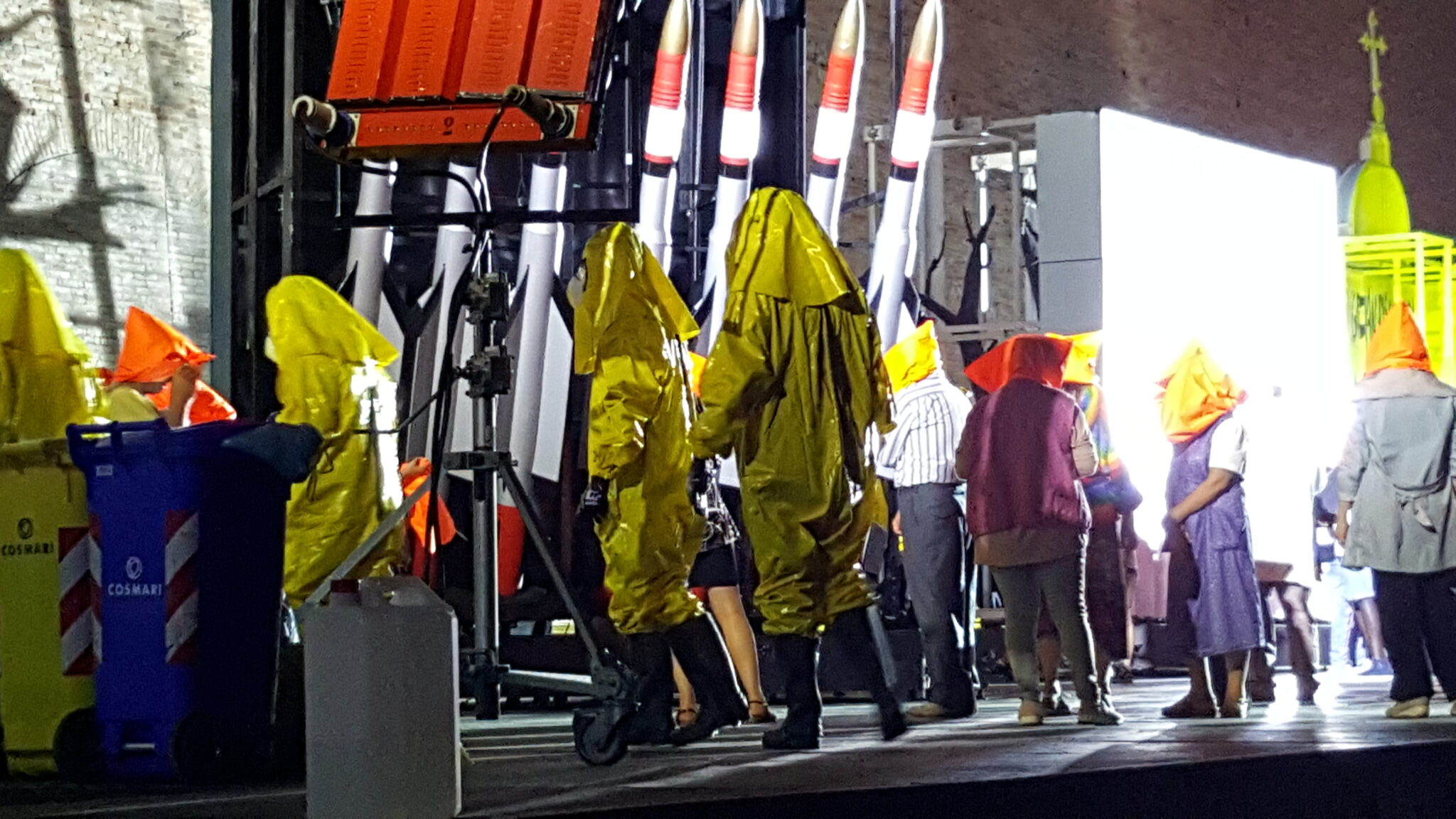

A hundred extras, taken by the citizens of the city of Macerata, have depicted a sort of contemporaneity seen by the director: gypsies camps, cars with open trunks full of African and non-EU citizens, populations and authorities of various ethnic and religious groups–Arab, Muslim, Christian–all to symbolize a heterogeneous mass of people located to the side and below the stage level. The palaces of power were on the stage represented by the building of the European Parliament that hides missiles (the Apple with the bitten apple on the wrong side) and the Vatican. Needless to see a parallel with Italian politics when on the left side of the stage was a bulldozer that threatened the gypsy camp. Italian citizens know well who and what this bulldozer represents.

The perception that took place at the beginning was then confirmed during the opera, with signs of political propaganda that ran in the hands of the actors from one side of the stage to the other. Wait a moment: wouldn’t we also see that at Mozart’s Magic Flute?

The English Director Vick has staged a totally provocative Magic Flute. First of all, it was in Italian and not in German. We all know about the eternal debate between those who want the dialogues and lyrics in the original language. Why lose the poetic nature of the script? There are those who are happy with the lyrics translated into their own language, sometimes not to lose the irony of dialogues, as in this case. This time, it was not just a literal translation from German into Italian, but there were numerous changes into the script to actualize it and contextualize it in the story that the director wanted to tell: a sort of paraphrase of contemporary Italian politics, very far from the original Mozart Opera.

There are also the traditionalists, who don’t tolerate representations too far from the author’s concept, and there are those who, with the justification of innovation, accept any novelty, no matter if it is good or bad. This time, in addition to the diatribe between the original script and translated script, between innovators and traditionalists, a political message was added, all focused on the current politics of migrants and on the policies of the Italian government. This has further divided the audience between right-wing and left-wing people, who contested or applauded.

Photo by Massimo Malavasi.

Another very questionable operation was in the interval between the first part and the second one. A part of the chorus refrain was taught to the audience. In this way, the show was restarted; all the entire audience’s Sferisterio could sing a Mozart chorus. This operation found much disappointment on the part of the audience.

The opera ended with the demolition of the palaces of power, and a great ballet of all the singers and extras, which reminded me of John Travolta’s choreography in the film Saturday Night Fever, but with Mozart’s music. All this lit by fireworks above the theater. In the end, the singers received the audience’s applause for their singing skills, but they clearly took a back seat to the arbitrary and bizarre choices of the director and costume designers. Extraordinary were Valentina Mastrangelo in the role of Pamina, Antonio di Matteo in the role of Sarastro, Manuel Pittarelli as Monostato, and a splendid Queen of the Night Tetiana Zhuravel.

Has the lyrical opera become a karaoke?

Why does a director have to distort such an Opera? Many composers cannot wait to write music for a contemporary story. If you want to send a message about current social problems, why don’t you write an original opera for this?

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Massimo Malavasi.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.