Tang Xianzu’s sixteenth-century classic, Peony Pavilion (1598), is a play about boundaries and transgressions – between wake and dream, passion and duty, innocence and guilt, the living and the dead, corporeal reality and ghostly appearances. And boundaries and transgressions are the core of The Interrupted Dream series, Danny Yung’s deconstructed reinterpretation of the play’s most celebrated eponymous scene. Premièred in Hong Kong in 2019, the latest version of Yung’s masterful reworking of the Ming Dynasty classic was revealed on 16-17 September 2022 at the Grotowski Institute’s Piekarnia, a performance venue housed on the site of a former garrison bakery in Wrocław, Poland, as the opening performance of the InlanDimensions International Arts Festival. On 24-25 September, it was also staged at the Shakespeare Theatre in Gdańsk.

Yung has never been afraid of boundaries – and of transgressing them – throughout his forty-year creative journey with Zuni Icosahedron, the art collective he co-founded in Hong Kong in 1982, and this work is no exception. Contemporary history, invoked with varying degrees of allusion in previous iterations of the series, takes centre stage in this most recent version. Yung’s newest production crosses what is, arguably, the ultimate boundary in current public discourse in Hong Kong, as it opens with footage of the 2019/20 Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill protests and explicit visual references to technologies of surveillance.

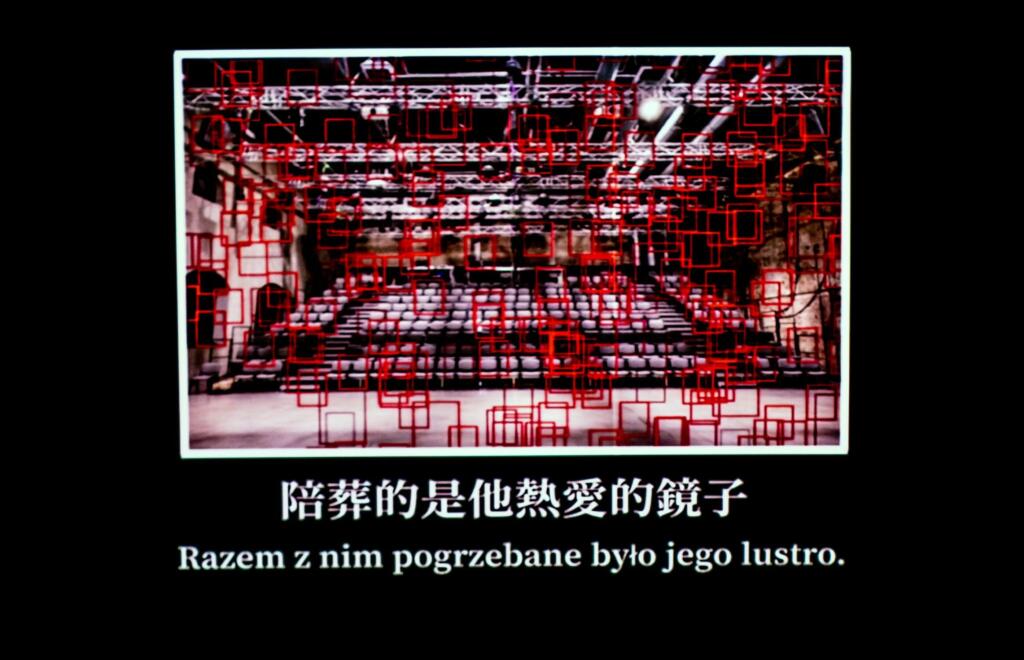

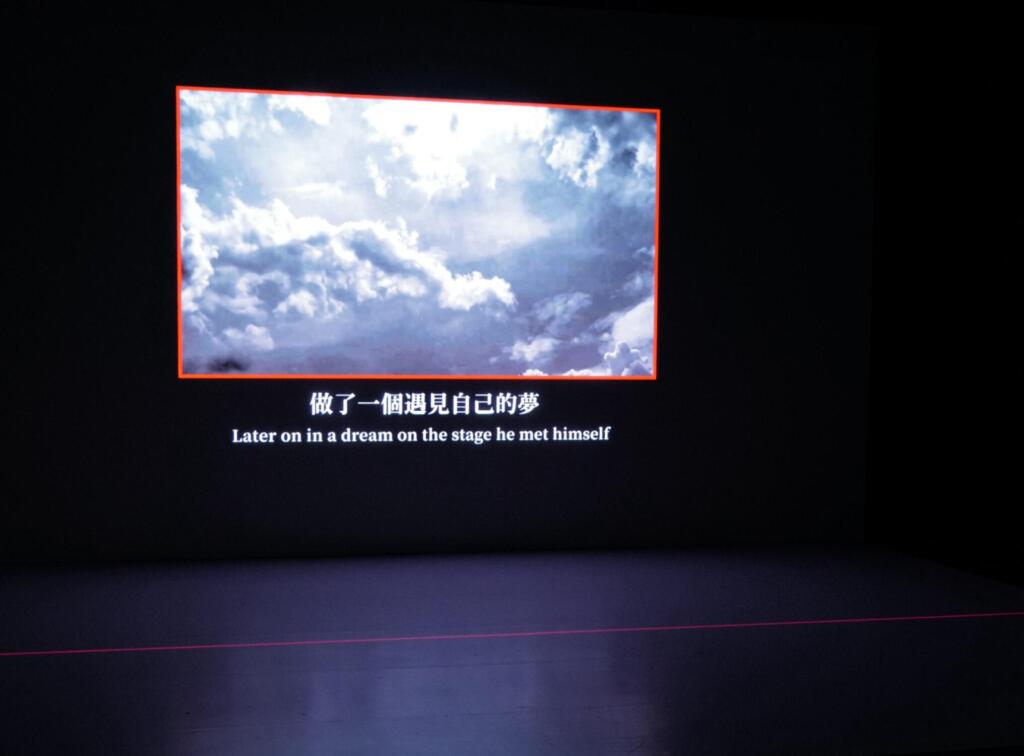

Emblematic of the production’s media design, a thin red line keeps appearing and disappearing on the back screen throughout the performance as if to signal a boundary to a forbidden zone, which the six performers onstage must negotiate with and push back constantly, almost ritually. Likewise, fast-multiplying red squares moving rapidly across the screen frame the faces of the protesters in the opening video footage – in an obvious nod to the ubiquity of facial recognition systems and control mechanisms during the protests, as well as throughout the Covid-19 pandemic.

“The Interrupted Dream.” Photo Credit: Tobiasz Papuczys, produced by Zuni Icosahedron, directed by Danny Yung.

Projections and intertitles such as “Recognition Self / Recognition World / Recognition Society” reinforce the motifs of identification and recognition, and so do repeated site-specific references to the theatrical venue where the performance occurs – and to the theatre, more generally. Such references implicate the spectators of the performance event as witnesses to the real-life events that take place outside it (at one point, a photograph of the Bakery’s empty auditorium appears on the back screen as a mirror to the audience). Such visual and textual devices underscore another central theme and symbolic cluster in the production, which revolves around the dialectics of seeing and being seen, watching and being watched, and foregrounds the theatre as a site of desire, voyeurism, and exhibition. As one intertitle tells us: “To peep or be peeped, to monitor or be monitored, is the essence of our reflection on theatre making.”

Outfitted in minimalist black and white costumes, the six performers take on different identities as lovers, dreamers, protesters, and historical ghosts. Through abstract ensemble actions, ritual rearrangements of tables and chairs (omnipresent in Yung’s stage designs), masked dances in Rococo-style costume, evocative Kun opera arias, and nostalgic Hong Kong pop songs, the audience is taken on a haunted journey across spatial and temporal boundaries to witnesses multiple, crisscrossing tales of personal and public, sensual and political longing and “interrupted dreams”: from the erotic spring dream in the forbidden garden of the aristocratic maiden Du Liniang and her scholar-lover Liu Mengmei in Peony Pavilion to the thwarted aspirations of Hong Kong’s contemporary dreamers. On the one hand, textual projections adapting familiar lines from Tang’s script and Kun actor Xiao Xianping’s redolent vocal rendition of celebrated excerpts from the classic opera version of the play anchor Yung’s rendition to the original Ming Dynasty dream narrative. On the other hand, media imagery (a poignant video of surging ocean waves recalls one of the best-known slogans of the protest movement, “Be Water”), sound (a chorus of protesting voices accompanies the opening video footage), costume (the black-clad performers wear balaclavas in one scene), and text – among other elements – reinforce its contemporary echoes in Hong Kong’s recent history.

“The Interrupted Dream.” Photo Credit: Zuni Icosahedron.

In Yung’s script, the forbidden garden stands for cultural taboos, the social marginalization of the arts, and the no-zone of civic protest. Yet, The Interrupted Dream deftly negotiates the red lines of taboos and forbidden zones to forcefully push the act of theatrical witnessing beyond the theatre’s margin, into the public sphere. Overall, this poignant and visually arresting reinterpretation of the sixteenth-century classic confirms yet again Yung’s standing as one of the leading theatre masters and most incisive cultural commentators of the contemporary Chinese-speaking world.

Production Credits

The Interrupted Dream

Directed by Danny Yung

Produced by Zuni Icosahedron, Hong Kong

An “InlanDimensions Festival” Programme

Bakery (Piekarnia), Wrocław, Poland

16-17 September 2022

This article was originally published by Zuni Icosahedron and has been reposted with the permission of the author. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Rossella Ferrari.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.