Musical drama of unlearned lessons is perhaps the most appropriate definition for Evgeny Pisarev’s loud, in all senses, performance Cabaret. If this premiere had taken place at the Theatre of Nations a year ago, the production would have been considered prophetic; today it seems a bitter, yet belated warning. However, back in 2009, Moscow already attempted to stage this musical, based on the autobiographical novel Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood and the play I Am Camera by John Van Druten. This musical failed, not because of the bad singing, but because of a lack of direction and a sluggish imitation of Bob Fosse’s iconic film. The film starring Liza Minnelli became the record-breaking Oscar winner – garnering eight wins from ten nominations – losing the statuette for Best Picture to the equally iconic The Godfather. A good year for a story about the dark years of History. Here too, today’s growing popularity of cabaret-style productions indicates that the most important Cabaret at the Theatre of Nations is both appropriate and timely. “Goodbye to Berlin” turns into “Hello to Moscow” with a feather touch.

«Nazi» on stage at the Theatre of Nations seems like a bad joke. Generally speaking, this play is brimming with jokes focused on the human and social bottom, which are sometimes balanced by the top end of the acting (Elena Shanina and Alexander Shirin’s duet), voice (Alexandra Ursulyak) and mimico plastic (Denis Sukhanov) heights. In Cabaret as in the not-so-crooked broken mirror, a lot of things are reflected in the associatively and emotionally shortened distance between the heroes of “the century past” and the audience of “the present century”. And actors sings in English and German – tearing voices and ripping hearts out of chests – the Russian-speaking audience does not need subtitles. They appear during the musical divertissements on monitors at the sides of the stage, but the audience either never take their eyes off the stage or bashfully, perhaps even dolefully, lower them.

The first act of Cabaret is electrified by the lust and debauchery of a collapsing empire (Berlin of the early 1930s), the second act is filled with the bitter private dramas of both people and country seemingly fascinated by evil. The last night of the Weimar Republic is played out in the smoky voluptuousness of a nightclub, in which Eros is defeated by Thanatos. Here the night seems sleepless, and at first light it is revealed that the sun is not a heavenly body at all but an earthly one. The scorching sun of one idea sizzles everything human in man and burns people. So dazzling, so blinding. The sun, of which the characters of Cabaret sing, “without knowing what they are doing” in the composition “Tomorrow Belongs to Me”, is recognizable from the first bars. Here they are singing in chorus, as if to illustrate the idea of the historical collective responsibility for crimes against humanity. Mass scenes (extravaganza) are one of the merits of the performance, in which greater attention is paid to external effects: from the wise and laconic set by Zinovij Margolin (the central image – a tilted building on the break of epochs), to the costumes – as if borrowed from a museum or sewn from the paintings of German expressionists by Viktoria Sevrukova. It’s a catchy, pouncing production in which one finds Brecht, Fassbinder, and Dietrich of The Blue Angel as well as a head-on, a collision-type question to the audience – “What would you do?” in those “given circumstances” – like a 1930s black market, at times, the production itself resembles a dark cabaret.

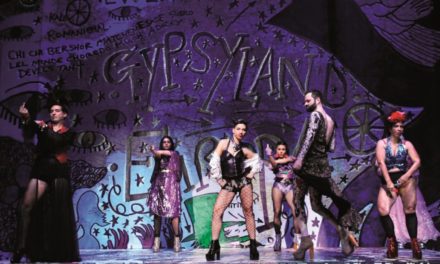

Cabaret at the Theatre of Nations. PC: press photo.

At first glance, Cabaret may seem pretentious and vulgar because of the abundance of fanfare, glitz and glamour. In fact, the performance illustrates how the brightly draped Germany of the 1930s was, unwilling to notice what was inexorably germinating within it. Instead of washing away the brown dirt and mold, they painted over it until it erupted again and continued to spread. Cabaret reminds us of a time when it was not too late, when the killing of millions could have been avoided. The spectators of the play see and know what the characters, busy with survival, carelessness or apathy, refuse to notice. And so it transpires in the finale that it’s not the outfits -or lack thereof – but the thoughts they evoke that are the most provocative in the play. From the decadence of morals to the decadence of the country, from hedonism to the heartbreaking hysteria of history, a performance in which sexual and political orientations are interwoven in a bizarre manner is on its way. The lack of freedom in the play is compensated for by sexual freedom. Theatre, however, does not descend into a brothel, but reminds one of its purpose as a home for the public. And at home, it is customary to speak frankly and straightforwardly. This “straightening” of certain images and themes can seem like a simplification against the background of the now popular meme “everything is not so simple”, but the format of the show and the cabaret style does not conflict with it.

The popular idea that “History repeats itself: first as tragedy, second as farce” is most wounding in that history repeats itself and the world is given three attempts to retake the unlearned lesson: the event itself and its tragic and farcical reincarnations. In Evgeny Pisarev’s sardonic Cabaret, carnal farce prevails over carnivorous tragedy, and the burlesque is given more attention than the petrel. We are not talking about the bird that heralds the storm, but about the cabaret of the same name from the play next door, Mephisto at the Chekhov Moscow Art Theatre, directed by Adolph Shapiro and based on the novel of the same name by Klaus Mann. If Cabaret is an escape from reality, Mephisto is the sad outcome of such an escape. And yet there is hope, and Cabaret provides us with that hope more than ever before. The historical certainty superimposed on the uncertain fates of the characters in this musical melodrama leaves gaps. Herein lies hope, and hope is well worth the price of admission. “Money makes the world go round” echoes from the stage and echoes in the audience.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Emiliia Dementsova.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.