It’s about two years since I moved to the Oresund region, the liminal place between southern Sweden and eastern Denmark – also known as the greater Copenhagen area. Though I have begun to learn Swedish, I cannot say I am yet equipped to follow the Scandinavian theatre classics without a translation. Should this stand in the way of my now twenty-five-years long commitment to documentation of theatre-going experiences? I believe not. Because theatre is much more than just a matter of mediated words.

I first visited the Betty Nansen theatre in Copenhagen back in 2004 as part of its collaboration with the Northern Stage theatre in Newcastle where I worked as the company dramaturg. That was a wholly different era of artistic leadership and programming politics but, when post-Covid travel across the Oresund bridge returned to normality, Betty Nansen was incidentally the first theatre I visited in Copenhagen (again) due to another personal connection. This was an invitation from an acquaintance to the closing night of an all-female production of Animal Farm, directed by the theatre’s vibrant – female – artistic director Elisa Kragerup, renowned especially for her forays into music theatre. (This production of Animal Farm, for example, featured the Danish electro pop diva Lydmor as one of the nine-strong ensemble of actors rolling in the neon-lit mud pool.)

Animal Farm by Elisa Kragerup.

It was the sight of microphones and musical instruments suggestive of a gig atmosphere in the promotional material for the Betty Nansen theatre’s new premiere – The Iliad, directed by Amsterdam-based Norwegian-born director Eline Arbo – that drew me in this time. Having recently studied the phenomenon of gig theatre, I am really interested how this trend of fusing the aesthetics of popular music with theatre plays out in different cultures.

It might be relevant to pause here for a bit on the Betty Nansen Theatre itself. Sitting at the back of the balcony for the first time, its architecture is striking – it is an unusually elongated rectangular structure whose long sides are lined with only two rows of single seats, set at different heights – like some kind of two-tier gondolas – both turned to face the stage rather than the auditorium below. I read later that when it was first founded, back in the 19th century, this was a vaudevillian entertainment sort of venue, where, I am guessing, the balcony seats used to look down on a much deeper stage than it is today. A subsequent focus on naturalist drama must have brought in the fourth wall and pushed the thrust further back to create a proscenium arch. This turn away from entertainment and towards serious drama was also facilitated by Betty Nansen herself, the Danish actress who left Hollywood after an unsuccessful stint in the film industry and returned to Copenhagen in 1917 to work as a theatre director and manager of this venue which she named after herself. After her death in 1943 the theatre changed its name and programming approach a few times – focusing at one point on youth theatre – before it was named Betty Nansen again in the 1970s. This potted history suggests to me a long-term feminist and progressive urge within the district of Frederiksberg, a part of Copenhagen which, it must be said, is notably clean, tidy and probably quite expensive. It is precisely this tension between the exterior and the interior that really works and could be, in my view, pushed further.

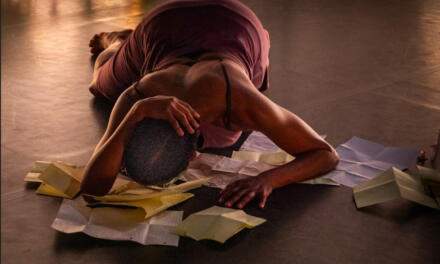

The Iliad. PC: Camilla Winther.

The Iliad. PC: Camilla Winther.

This is also, in a nutshell, what I got from this production of The Iliad: a screamingly brave concept that is strapped back by the force of some as yet undemolished conventions.

The director Eline Arbo has worked with the writer/ dramaturg Tom Silkeberg on parts of an existing Danish translation of the Iliad. Specifically the plotline dealing with Agamemnon’s abduction of Achilles’ sex slave Briseïs, serves as a prompt for problematizing various nuances of the issue of gender, gender imbalance, and masculinity in particular. Even with a limited access to the dialogue (which is a pity, by the way, at the time when so many European theatres find ways to offer subtitles in English), it is hard not to read the choice of this subject matter against the backdrop of the ongoing war in Ukraine. Dissecting and subverting the ‘Greek (war) hero’ archetype, here we encounter instead rhetorical heroism that conceals fear and cowardice, as well as soldierly naivity, reluctance, bravado, power-seeking, homoeroticism, bromance, and male grief over various kinds of loss. For me a stand out performance comes from Ena Spottag’s tough but pure-hearted Hektor (maybe because I also remember her as a similarly complex Benjamin in last year’s Animal Farm).

Visually we are in a crumbling abattoir – a space once upon a time tiled in white and now suggestively decrepit – where much thick stage blood is clinically decanted out of containers and onto carefully laid out sheets of sheer plastic. It is not clear whether this is part of the stage metaphor or a health and safety issue, but the audience goes along with it. Much more interesting are Ida Marie Ellekilde’s costuming choices as she dresses the cast in shiny blacks, crossing haute couture with elements of Nazi uniforms, work clothes, and subtle hints of goth rock or metal.

Another important collaboration at the base of this production is between Arbo and composer Thijs van Vuure which results in enabling the acting ensemble to also perform as singers/musicians in a seamless and fully integrated way throughout the show. Possibly because of my still vivid memory of the depiction of the Trojan war as an hour long drum solo which brought down the tiled walls of the set in Christopher Rüping’s Dionysos Stadt (2018) at the Munich Kammerspiele, I expected a more rousing musical performance in this production, but that, I understand, is coming on 15th April 2023 when the all-female Danish death metal band Konvent take to the stage to perform their gig on the set of this Iliad as part of the Roskilde Festival. Certainly a good reason to visit the immaculate neighborhood of Frederiksberg again.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Duška Radosavljević.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.