The play is based on the charges against one of France’s biggest companies, Lafarge, and how it allegedly paid money to militant groups.

BERLIN – For Syrian playwright Mohammad al-Attar, deconstructing the complicated nature of the war in his home country has formed the basis of much of his recent work.

In his latest stage production set in the country, he takes a closer look at these complexities, exploring the toxic alliance between money and power and the role it has played in Syria’s destruction.

The latest collaborative effort between Attar and his creative partner, Syrian director Omar Abusaada, The Factory is based on the true story of an ongoing legal scandal involving Lafarge, one of France’s biggest companies.

Praised by critics, The Factory has already had two successful runs in Germany, including packed shows at Berlin’s most famous theatre, the Volksbuhne, in October. It will now travel to the Greek capital Athens for a series of performances beginning November 8.

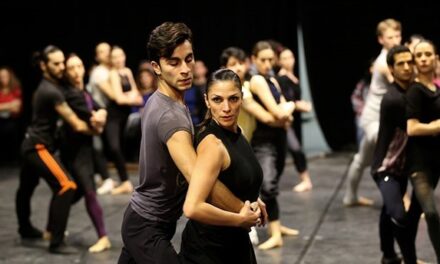

The play revolves around the stories of four characters, two who are real people and the others fictionalized, involved in the current scandal (Courtesy of Ant Palmer/Ruhrtriennale 2018)

Construction giant Lafarge is currently under investigation in France for its involvement in Syria between the outbreak of the revolution in 2011 and 2014. The company has been charged with complicity in crimes against humanity and financing terrorists following allegations that its Syrian subsidiary, Lafarge Cement Syria (LCS), paid nearly €13m ($14.8m) to armed groups, including the Islamic State (IS), and endangered the lives of its Syrian staff during the early years of the civil war.

The scandal was brought to light in France by French-Algerian journalist Dorothée Myriam Kellou two years ago after it was published in Zaman al-Wasl, a pro-opposition Syrian news website.

Lafarge opened up its factory, considered Syria’s biggest foreign investment, in 2010 in Jalabiya, a city near Raqqa in the north of the country. As the violent crackdown on protesters began and international sanctions were imposed, multinational companies began pulling out of the country. Lafarge, however, insisted on keeping the factory open in order to be ready for business as soon as reconstruction began.

The area soon became one of the most dangerous in the country, and by the end of 2013 IS had taken full control of the region. According to investigators, Lafarge paid money through intermediaries to various militant groups to ensure the continued free movement of its staff and goods.

Lafarge, which is today one the world’s biggest cement producers following its merger with Swiss company Holcim three years ago, is now facing questions around what payments were made, who in the company knew about them and whether international sanctions and their responsibilities were ignored.

The company said that it will appeal against the charges, adding that it took immediate action against individuals involved in the case.

“None of the individuals put under investigation is today with the company,” Beat Hess, board president of LafargeHolcim, said in June.

Last year, the company’s internal investigation found evidence that the local factory provided funding to a number of armed groups through intermediaries.

For 38-year-old Attar, the scandal presented an opportunity to look at the many metaphors about Syria that lay within it.

“The hierarchy of power and money in Syrian society was reflected within the power structures inside the factory, so the story was a good way to shed light on this as well as the wider context that has led Syria to where it is today.

“From a European perspective, meanwhile, it’s a strong reminder that the struggle in Syria is not an issue for Syrians only. It’s a struggle that many foreign powers have stakes and shares in, and Europe is not an exception,” says Attar.

Between fact and fiction

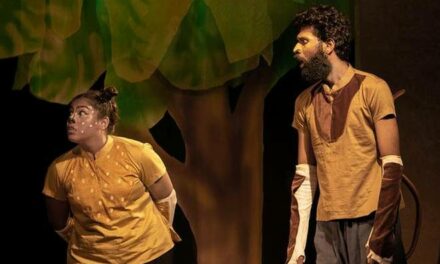

The play, which runs at just under two hours, has been described as part documentary, part fiction and features four characters based on people involved in the real-life story.

During the pre-production process, Attar spoke with various figures connected to the scandal, including journalists such as Kellou, former Lafarge workers and employees who worked at the factory and at the company’s headquarters in Damascus and other cities. Despite his attempts, Attar says he was unable to reach anybody within Lafarge.

The play revolves around the stories of Ahmad, played by Syrian actor Mustafa Kur, a maintenance worker at the plant; the journalist Kellou, played by Syrian actor Lina Murad; prominent Syrian tycoon Firas Tlass, whose family was once closely aligned with the Assad family, played by Lebanese actor Ramzi Choukair; and Amr, the character of a businessman born in Damascus who emigrated to Canada at a young age, played by Syrian actor Saad al-Ghefari.

Through their individual monologues and conversations with each other, audiences are exposed to the various sides of this tangled and complicated story. Ahmad, a young father from Damascus, recalls a tough working environment where Lafarge bosses were more concerned about keeping the factory running than the safety of their workers.

As the security situation deteriorates and colleagues are kidnapped, he must choose between risking his personal safety over losing his job. Being late because of the fighting, he says, became a sackable offence.

In one monologue, Ahmad recounts the night when he and his colleagues were left inside the factory as Islamic State militants drew closer. With little support from the bosses, 29 men were forced to flee the factory in just three vehicles–a minibus, a car, and a motorbike. Ahmad’s character is not based on just one worker–it is a combination of the stories of a few factory workers and the different details they provided.

The character of French-Algerian journalist Dorothée Myriam Kellou is played by prominent Syrian actor Lina Murad (MEE/Gouri Sharma)

In the play, Maryam, the character based on Kellou, speaks of hypocrisy in France, where teenagers were being arrested for social media posts about IS, while at the same time one of the country’s largest companies was doing business with the group.

Through the character of Tlass, a well-known figure among Syrians who had a small share in the company, audiences get insight into pre-war Syria and the relationship Syrian businesses were beginning to enjoy with their French counterparts. Despite his closeness to the Assad family that dates back to childhood, Tlass later defected to the opposition and his assets were frozen.

Amr, the founder of a multi-faceted business covering industries like environment and water, reveals how he returned to Syria in 2000 after Assad assumed the presidency and started slowly liberalizing economic policies.

Speaking both French and Arabic, he saw an opportunity in helping foreign investors access the Syrian market. Employed by Lafarge to manage environment and security issues, he boasts about helping the company get the best water treatment system in the whole country.

Despite being based on a true story, Attar says some of the individual narratives are more fictional accounts than factual.

“When you are responding to a case that is ongoing, there’s still a lot you don’t know so you can liberate yourself from this limitation by using fiction. While there are traces of both, my work is not presented as a piece of investigative reporting or as [a] legal thesis. It’s a play, and fiction can help cover the missing pieces of the puzzle.

“When I presented the four characters, I wasn’t interested in representing them biographically. I was more interested in exploring the roles they occupy in the struggle, the values and the ethics they defend, how their perceptions and narrations of the story differ depending on their positions, and finally, what kind of future they may face. And for that I needed fiction,” Attar says.

According to Attar, working with fiction is a particularly effective tool when the topic is as difficult as the war in Syria.

“Sometimes fiction is a natural response to the unbearable. What’s happening in Syria is not understandable or bearable,” he says.

The play ends with each character concluding their own story. Ahmad’s monologue is a particularly compelling section where he speaks about the conditions that led him to flee his country and start life as a refugee. It serves as an important reminder to European audiences about the roots of the current refugee situation.

Syria on stage

Born in Damascus in 1980, Attar has two degrees from the city’s Higher Institute of Dramatic Arts–in English literature and theatre studies–and a master’s degree in applied theatre from Goldsmiths, University of London. He is recognized on the international stage as one of the most important chroniclers of the Syrian war, with his plays performed at theatres in London, New York, Delhi, Tunis, and Beirut.

In The Factory, Syrian playwright Mohammad al-Attar explores the toxic alliance between money and power in the context of the war in his home country (Photo courtesy of Isabelle Meister)

Much of Attar’s work is a collaboration with director and playwright Abusaada, who was two years ahead of him at the institute in Damascus. The pair have been working together since 2007.

Attar arrived in Berlin from Damascus via Beirut in July 2015 through a programme for politically persecuted authors, and the pair have since collaborated on a number of productions based on the war.

One of their major works has been the trilogy based on Greek tragedies–Euripides’ The Trojan Women (2013), in which they worked with amateur Syrian actors and refugees living in Jordan, documenting their experiences with war, love, and sacrifice; Antigone Of Shatila, which has played in cities including Beirut in 2014, and raises questions around the role theatre can play in understanding what’s happening in Syria; and Iphigenia in 2017, which explored the experience of the Syrian war through the perspective of women.

Syrian Omar Abusaada is the director of The Factory (Photo courtesy of Isabelle Meister)

With The Factory highlighting some of the bigger issues at stake, Attar says that he hopes it will provoke audiences to dig deeper.

“With this play, I was aware that it would be seen primarily by European audiences and I wanted it to push people to look at Syria from different angles. It’s not just a war that is happening beyond or between radical Islamists and the Assad regime–it is a proxy war where today, international and regional powers have the upper hand on deciding the fate of Syrians.”

This article appeared in Middle East Eye on November 6, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Gouri Sharma.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.