Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun, as anyone reading this knows, is a cornerstone of American drama. It’s the first play by a Black woman to be produced on Broadway (in 1959), the first Black play to be securely canonized and broadly popular, the first to attract a large Black public, and the first commercially successful play to depict Black life entirely free of stereotypes. For all its acclaim and renown, though, the play has also been an object of heated debate over the years, even among its admirers. What’s more, it has been so frequently produced that some of its characters have become stereotypes.

The plot spring is an insurance check. The Younger family—squeezed three generations together in a small and squalid apartment with shared bathroom—disagrees over what to do with the payout for their deceased patriarch. Mama Lena isn’t sure, and her son Walter Lee, seething with resentment from thwarted ambition and humiliation in his chauffeur job, tries to browbeat her into financing a liquor store. Feisty Beneatha, Walter’s sister, is a college student fired with nascent feminism and African pride who hopes for financial help with medical school. Walter’s bitterness and bluster have begun to curdle his marriage to long-suffering Ruth, who is pregnant and considering abortion. Seeing the family splintering, and sick of the daily insult of their tiny flat, Mama decides to buy a house in a white neighborhood . . . which prompts a friendly white community rep to try to bribe the Youngers not to move in.

From the day it opened, this play’s enormous popularity made it suspicious to some. White reviewers back then acclaimed the Youngers’s universality and respectability, how reassuringly similar they were to everyone else! Who, after all, couldn’t empathize with wanting to own a home or start a business? Liberal Blacks, for their part, acclaimed the play’s Civil Rights angle, regarding the family’s defiance of shameless housing discrimination as the moral of a straightforward allegory.

Amiri Baraka put his own spin on the white line, deriding Raisin as assimilationist and “middle class.” Ossie Davis, who understudied Sidney Poitier as Walter in the Broadway premiere and later took over the role, described unease in the cast about the white response. White audiences loved Mama more than anything, viewing her as a heroic force of order and calm who was wise and powerful enough to blunt Walter’s scary rage at the play’s climax. Practically no one commented back then on the complex tensions within the play’s Black world—the many clashes of gender, generation, and class that sometimes had radical implications. Hansberry, a lesbian and Communist, considered Raisin a “half-victory.”

All this public debate is crucial background to Robert O’Hara’s extraordinary revival of Raisin, now running at the Public Theater. This production seems to me a brilliant and inspired effort to correct the skewed perceptions in productions past. I have seen five other versions of this play, including two on Broadway, but none has struck me as so thoroughly and realistically infused with urgent Black issues as this one. O’Hara’s show rings and bristles with BLM defiance and horror at our current, viciously revanchist and racist right wing. More important, everything from the actors’ gestural language to the stage set to the director’s few pivotal changes to the script, feels flush with fresh observation of the play and Black life.

I was a student at Yale Drama School in 1983-84 when Yale Rep—then led by Raisin’s original director Lloyd Richards—produced the play’s 25th anniversary production, directed by the distinguished poet, playwright and actor Dennis Scott. Dennis visited our class one day and told us that, out of respect for Lloyd, he felt he had to use Lloyd’s landmark production as a stylistic model. I remember thinking that a disarmingly honest remark. It certainly helped explain why Dennis’s production struggled to make a lasting impression of its own.

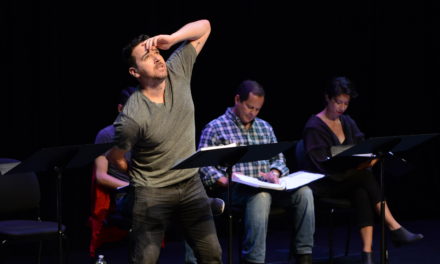

PC: Joan Marcus

The last half century, it must be said, have produced hundreds of comparable homages and facsimiles that have continually affirmed the play’s classic status but also left its cultural-political profile more and more vague and gauzy. In 1986, George C. Wolfe made Raisin the object of a sharp lampoon in the “Last Mama-on-the-Couch Play” section of The Colored Museum, which skewered its profusion of kitchen-sink clichés and white-gaze stereotypes.

O’Hara’s production summons the ghost of The Colored Museum just by appearing at the Public, as Wolfe’s play did. Nevertheless, this Raisin is electrifying. I would never have thought any staging could make me feel I was seeing this play for the first time again, and yet this one did. Not one other Walter I’ve seen—not Sidney Poitier, Delroy Lindo, Sean Combs, Denzel Washington, or Danny Glover—has blazed with the incendiary, unapologetic anger and deadly self-loathing of Francois Battiste. Arriving home late and drunk in the silent opening scene (an O’Hara add-on), Battiste’s Walter struts across his own dark house with a jive hitch-step that is funny only because he’s alone. His solitary action makes clear that he has to fantasize about power in his cups because he never, ever tastes it in reality. When, soon after, Ruth (Mandi Masden) wakes up and makes him food, he flirts with and then bullies and needles her with such venom and disgust you fear for her safety and want to shout “flee!” This couple is in deeper trouble than any other Walter and Ruth I’ve seen. In fact, O’Hara moves the one intimate scene Hansberry wrote for them offstage, muting it as a voiceover with sounds of love-making.

The point is, no Mama in the world—not even the one played by the formidable Tonya Pinkins here as a fascinatingly fragile and authoritative matriarch—could possibly defuse such an erratic, belligerent, powderkeg of a son. Battiste’s portrayal hasn’t a scrap of deference (as Poitier’s roles always did) to white fears of angry Black men. Walter is O’Hara’s linchpin. He even thrusts the character physically to the fore near the end in a sequence that breaks the fourth wall—at the play’s most painful moment, when Walter imagines groveling like a minstrel character to the white community rep. Instead of stressing Lena and Beneatha’s disgust at this speech, as most directors do, O’Hara brackets it as metatheater, pointedly implying that no viable future can exist for anyone in Walter’s world as long as men like him are permanently sidelined and belittled. Hansberry’s critique of the American dream feels more specific and trenchant here than Death of a Salesman’s.

There is much, much more to admire. Paige Gilbert’s marvelous performance as Beneatha brings all that character’s delightful pluck, intelligence and humor into unique focus. Clint Ramos’s emphatically tatty set design is the first I’ve seen that honestly shows what the dilapidation and grime in the Younger apartment would really look like after decades of slumlord neglect. A scene I’ve never seen before (because it’s usually omitted) is also powerfully included here, showing a Black neighbor politely trashing the Youngers’s aspirations to rise in the world. O’Hara also adds a shocking coda, clearly meant to forestall any thoughts of a happy ending, that reveals some likely racist repercussions after the family moves to their new home.

This Raisin is self-evidently a hammer meant to smash a chestnut. But it’s also a fascinating and necessary conversation across time between major Black artists, as well as proof that fresh and newly nourishing fruit can yet be harvested from a venerable and sturdy tree.

A Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry

directed by Robert O’Hara

The Public Theater

This article was originally published on jonathankalb.com on November 9, 2022, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Jonathan Kalb.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.