Author of Terror, Ferdinand von Schirach. Photo Credit: Annette Hauschild/OSTKREUZ

With his debut play Terror, the lawyer and best-selling German author Ferdinand von Schirach conquered the stage. An interview on the theatre, criticism, and society.

Mr von Schirach, how did the play Terror come about?

Originally, I wanted to write an essay on terrorism for Spiegel. But it became too complex. It simply worked better when I talked to someone about it. You see, one problem with journalism is that texts hardly ever lead to a discussion. Newspapers are always going on about “debates,” but in fact, they consist in only three or four journalists writing something about a subject. A few years ago I wrote in Spiegel about the case of the child murderer Gäfgen that I believe it’s always wrong to threaten torture. The next day I received well over 1,000 e-mails, some of which threatened me with torture. That isn’t a discussion. It changes nothing. But democracy needs discussion; that’s its essence.

The dramatic form thus emerged for you from the material …

I wanted us to talk about how we want to live. Terrorism is the greatest challenge of our time; it is changing our lives, our society, our thinking. How we deal with it isn’t just a legal question. It’s an ethical-moral decision. A court case is suited for the stage because at the bottom every criminal trial resembles a stage play. It follows a dramaturgy; it’s not an accident that theatre and courts have the same origins. Even today the participants in a case “re-enact” the crime – not through actions, of course, but in language.

The trial in the play revolves around whether a fighter pilot should have been allowed to shoot down a hijacked civilian aircraft. He wanted to prevent it from being turned against a football stadium full of people. The pilot is charged with multiple murders, though he may have saved thousands of lives. In the play, you’re actually referring to a judgment handed down by the Federal Constitutional Court in 2006 and playing out a fictional case against the backdrop of an apparently ever more realistic terrorist threat. But in the discussion of fundamental principles before the court, you also pose the far-reaching legal question of the power over the life and death of other people.

Every important question has a historical reference. We’re not the first age to have thought about something; everything is interwoven in our history, our civilization. From the beginning, theatre was a reflection of society – as were the courts. In Attic life, in the direct democracy, courts and theatre resembled one another more than they do today. Both had only one task: they were to serve the self-reassurance of people and strengthen the endangered state. Only much later, only in Rome, did law become systematic. That has advantages of course; courts became more predictable and lost their arbitrariness. But the Greeks wanted something very different. They were probably the only people ever who actually loved court trials. They were concerned exclusively about the power of argument. The citizens stood directly before each other; there were no lawyers or prosecutors, but 6,000 judges for only 30,000 inhabitants. In a small society, things were possible that would be unthinkable – and very dangerous – today. And the theatre of the Greeks treated the same questions as did their courts.

The Oresteia culminates in the grand finale of a court trial. Does this ancient Greek-democratic legal idea also underlie your play Terror?

The important thing about the Oresteia is the transition from revenge to an orderly trial. This is what appeases the Erinyes. In the theatre, the audience can influence the outcome of a play. The outcome isn’t determined by anger or hate, but by deliberation and discussion. Perhaps that’s a similarity. The theatre is in this also superior to film. When you consider as a writer what you can make out of this unique constellation, the idea of letting the audience vote is fairly obvious. The result is different again the next day because they are different people who go to the theatre with different pasts, different desires, and different hopes. That can be interesting. And if it’s announced at the beginning of the play that the spectators will have to make a decision at the end, they listen very differently. They want to decide morally and fairly, they want to do the right thing. But what is the right thing? The play poses this question.

So you see the theatre as a place of discussion?

That’s the best possible thing the theatre can be.

For a new play, Terror was extraordinarily successful; it was immediately performed at numerous theaters, was very well attended and went down excellently with the audience. After the Berlin premiere, I myself witnessed the audience discussing not the staging but rather the content of the trial.

You’re right; it’s not director’s theatre. The play is pretty robust because it’s about ideas. The heroes of the play aren’t the defendant, the defending attorney, the prosecutor or the judge. On the contrary. The better the actors are, the more they disappear behind their roles. I too, as the author, disappear altogether. The only heroes left then are, if you like, the law and morality. That’s the aim of the play. The audience abstracts from the actors. They don’t discuss who put in a particularly good performance, but rather what the defending attorney said and whether it’s right. At the premiere in Düsseldorf, the prosecutor put a question and one of the audience called out: “The question is inadmissible.” Of course, the audience knows that they’re in a theatre, but they take their role as jury seriously. The attacks in New York, Madrid, Paris, and Brussels have made it clear to us all that we must pose these questions. We’re looking for a way out of the dilemma.

Did it surprise you that initially the performances always ended in acquittals?

No. It’s our first impulse, after all, to say it’s better to sacrifice fewer people to save many. That accords with our normal life. Everywhere we choose the lesser evil. What surprised me was that 40 percent of the audience thought the very complex arguments of the state prosecutor were right. That speaks for the open-mindedness of the theatre-goers. The voting is almost always 60:40 for acquittal. But actually it doesn’t matter whether we condemn or acquit the pilot; what matters is that we become aware of how pressing these questions are.

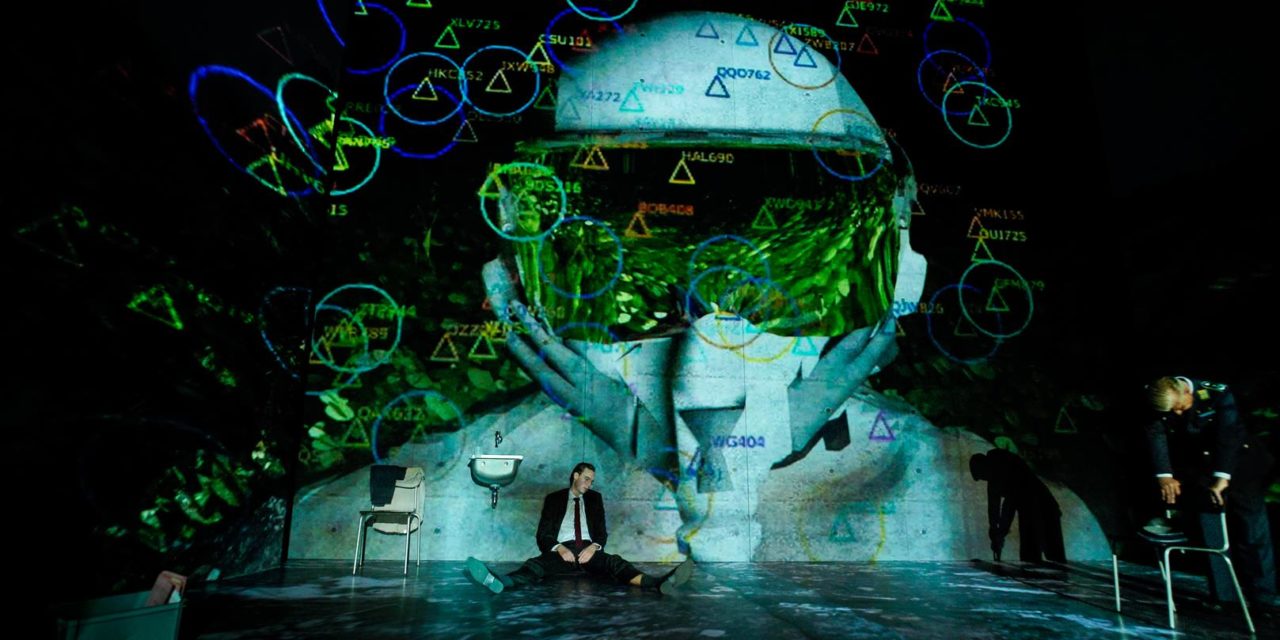

Ferdinand von Schirach’s Terror. Director Hasko Weber, Set Thilo Reuther, Costumes Camilla Daemen, Video-/Soundart Daniel Hengst, Dramaturgy Ulrich Beck, Deutsches Theater. Photo credit Arno Declair

My first impulse in reading the play was “acquittal.” And then the tide turned – surely also in the dramaturgy of the play. I would have therefore expected that the majority of the rather left-liberal theatre-going audience would plump for conviction. But perhaps I underestimated the presence of the actors and the sensuous effect of theatre.

What pleases me most is that many people go to the play who are not otherwise interested in theatre.

How many productions have you seen?

Ten. There have now been forty premieres; I’d have liked to see them all, but I simply can’t do it. Perhaps I can still see a few performances abroad. I’d like to see the premieres in Copenhagen, Tel Aviv, and Tokyo, for example.

Do you have a favorite production?

I was really happy about every premiere. Imagine it: you write a play at your desk at night and then it’s performed by the best actors at the biggest theaters. It’s a feeling of incomparable happiness. The play is perhaps most intense in a restrained production. The audience wants to reflect; they want to be able to concentrate. But that’s ultimately a matter for the director. Even art must be allowed to change.

Were you surprised by the overall rather reserved reception of your play by the arts pages and the critics?

It’s the job of the critic to criticize, that’s his profession. In the 1920s the theatre critic was the most important man at a daily newspaper. He was very close to the audience. The reader wanted to know where he should go in the evening, and the critic was there to tell him. That has perhaps changed. But a writer shouldn’t judge his critics.

Do you feel misunderstood?

Not at all. I’m delighted when the play is discussed. Look, in October the film adaptation of Terror will be broadcast on TV. Florian David Fitz, Martina Gedeck, Burghart Klaußner, Lars Eidinger, Jördis Triebel and Rainer Bock are all in it. It is directed by Lars Kraume, who just won all the prizes for Der Staat gegen Fritz Bauer (The People vs. Fritz Bauer). The broadcast will be shown simultaneously in Austria and Switzerland. Afterward, the individual countries will vote and the play will be discussed in a talk show. I was allowed to work a bit on the margin; it was a gift for me. I write exclusively for the audience, not for the critics.

Ferdinand von Schirach’s Terror. Director Hasko Weber, Set Thilo Reuther, Costumes Camilla Daemen, Video-/Soundart Daniel Hengst, Dramaturgy Ulrich Beck, Deutsches Theater. Photo credit Arno Declair

What was your connection to the theatre previously? Were you a regular theatre-goer?

When I was fifteen-years-old, I was allowed to play Leonce in our boarding school’s production of Büchner’s Leonce und Lena. And there on stage, I kissed a girl for the first time, Lena. She was two years older than me and the prettiest girl at school. We rehearsed the kissing scene again and again; it was marvelous. So I can say that from the start I’ve had a wonderful relationship with the theatre.

Do you already have plans for your next play? Some preliminary ideas?

Yes, I have a few ideas. But I’d rather not talk about them yet.

When you write plays, aren’t you not only an artist or a dramatist, but also a lawyer and educator?

I’m anything but an educator. The idea is repugnant to me; I have very few answers to questions. I can only pose questions. Of course, it would have been more difficult had I not known the state of the legal discussion. It does help a bit to know something about the law. But the play is a very idealized version of a trial. You can see this alone from the fact that, in reality, such a case would take many weeks and there would be hundreds of witnesses.

But it’s clear it has to do with your work as a lawyer.

I became a criminal defense lawyer because such questions interested me, that’s true. Back then I went to the law firm in Berlin that fielded the attorneys for the defense in the Honecker trial. Later I was fortunate to be the defending attorney in one of the most interesting trials of the post-war period, the trial against the members of the politburo. It was about questions that went beyond the merely legal. I don’t know anything about a civil law: I don’t much care whether the one side gets money from the other. In criminal law, the great social questions are discussed. In these matters at least, there’s no great difference between the work of a writer and that of a lawyer.

So your interests in jurisprudence and literature and drama have the same cause?

Yes. It’s our state, it’s us who have to decide how we want to live. This can’t become something abstract, something remote, or else our democracy will fail. Yet, I don’t look upon the theatre as an institution in charge of morality. It can be a place for enlightenment, in the philosophical sense. In a film of course much more is possible, but theatre is above all a forum.

The theatre is trying more and more to offer discussion events. Is that the right path?

It reminds me a little of the Protestant pastor who plays the flute in church so as to be contemporary.

You don’t think much of entertainment in the theatre?

No, I do, of course. But I’m afraid movies can simply do it better.

Can you imagine more topical material for a drama?

What are you thinking of?

Refugees, for example?

That’s one of the big subjects that moves our society, you’re quite right. Elfriede Jelinek has written intelligent texts on it. Today many people take notice of only very short texts; the headlines of the online portals of newspapers suffice them. But if we take democracy seriously, we must carry on discussions very differently. Democracy demands real discourse; it demands depth. If plays succeed in posing questions so that this becomes possible, so that they move the audience, no one need worry about the future of the theatre.

The interview was conducted by Detlev Baur for the magazine Die Deutsche Bühne. Reposted with permission of the Goethe Insitute. Read an original post here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Detlev Baur.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.