South African Indian actor and director Gopala Davies’s production of Les Cenci: A Story About Artaud premiered at the National Arts Festival in Grahamstown in 2016. The production celebrated the 20-year partnership between The French Institute of South Africa (IFAS) and the National Arts Festival (NAF). The production was staged at the Con Cowan Theatre in Johannesburg later in the year.

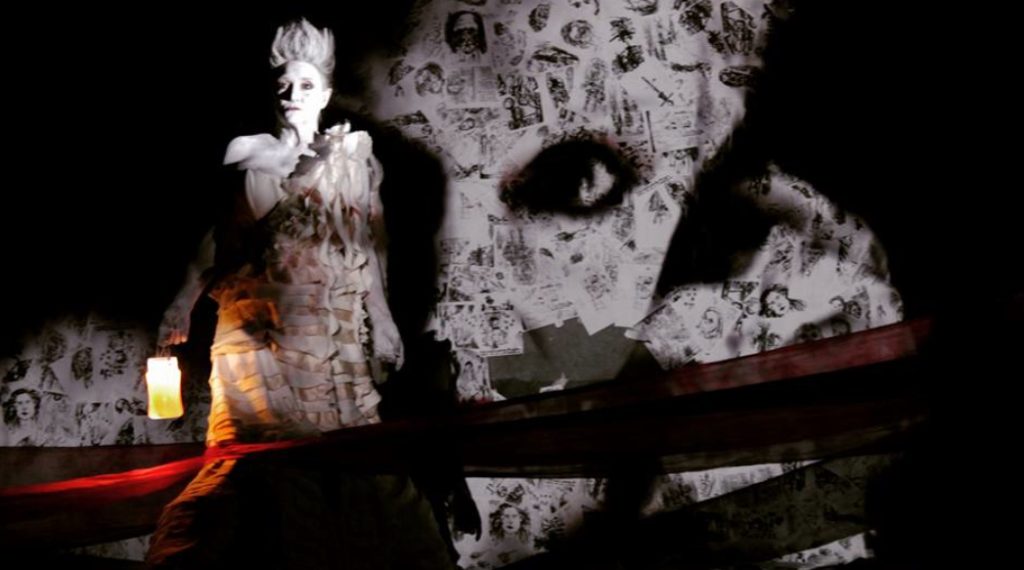

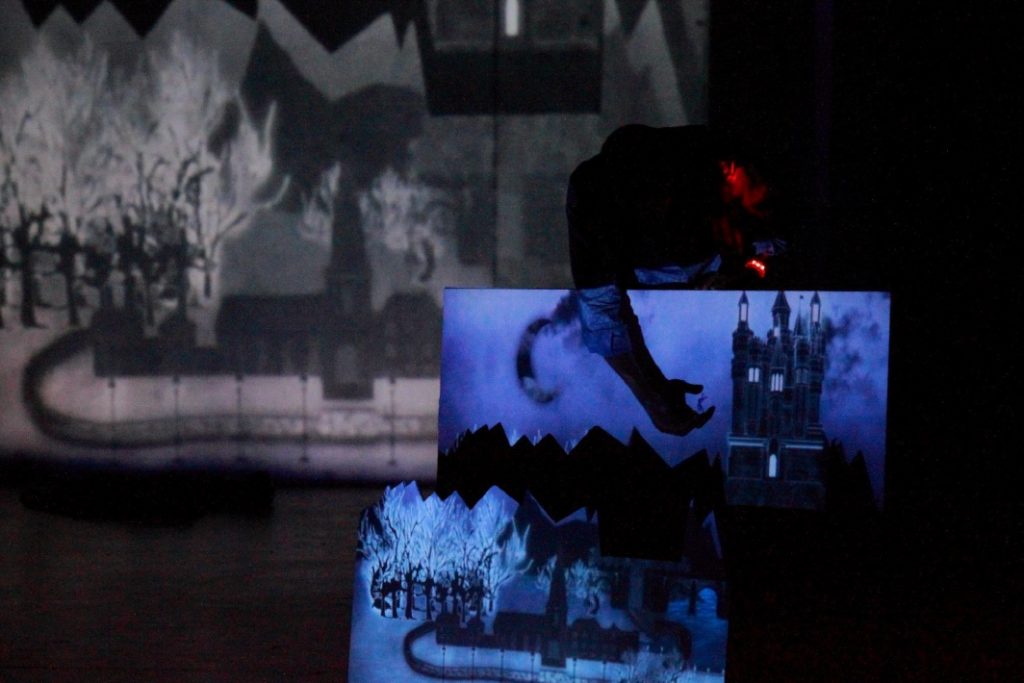

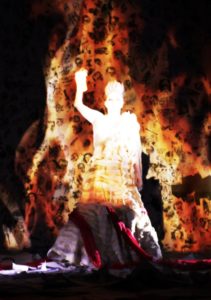

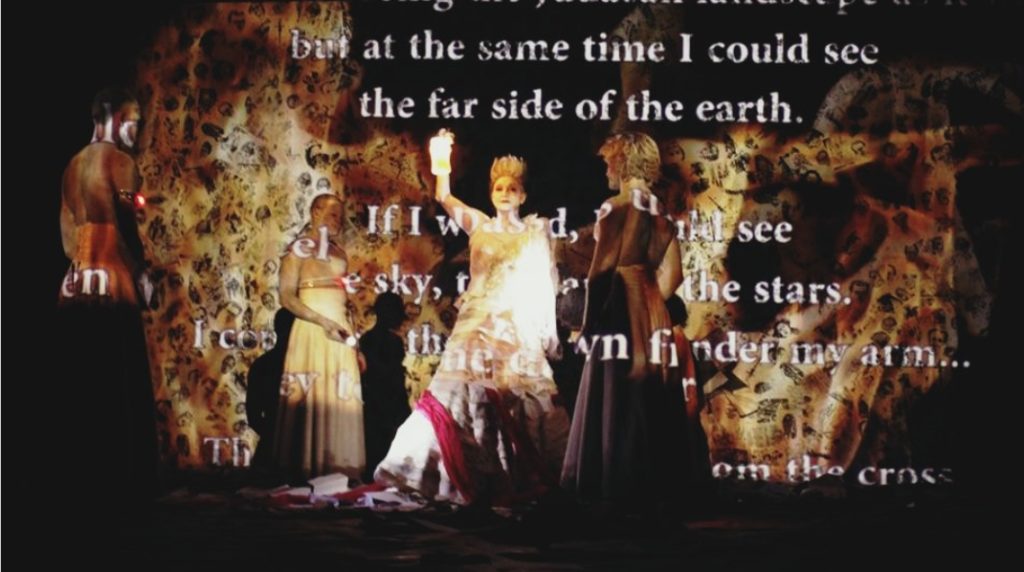

Davies’ production was a semi-autobiographical exploration of the life and ideas of Antonin Artaud (1896–1948) and centered on Artaud’s turbulent encounters with mental illness. Davies specifically explored the distortion of memory in/through mental illness. Davies drew inspiration from Artaud’s The Theatre and Its Double (1938), as well as Artaud’s ill-received Les Cenci (1935). Butoh influenced his use of physical language and physical imagery for live performance. The production interspersed the horrific with humor and in doing so, created a jarring cognitive and emotional incongruence. Further, the production’s visual spectacle, disjunctured soundscape, rejection of plot and linearity, rejection of any unity between space, time and action, fractured narrative and emphasis on physical language created both a heightened sensorium and sensory dissonance that resonate with Artaud’s vision for the theatre. Davies’ innovative use of technology was the catalyst activating this ‘synaesthetic’ theatre experience. According to Davies, his explorations in intermediality centre on mediating bodily encounters by the simultaneous blurring of the virtual (recorded performances and imagery) and visceral (live performance) through the juxtaposition of the screen and stage spaces.

Les Cenci: A Story About Artaud follows Davies’ Barbe Bleue: A Story about Madness (2013-2015), Davies’ first venture into intermedial theatre. There were several iterations of Barbe Bleue in the period between 2013 and 2015, allowing Davies to experiment with various interfaces between liveness and recorded performance, as well as the possibilities of the technology he used. Similar to Les Cenci, Barbe Bleue also dealt with mental illness. Barbe Bleue used the story of Bluebeard as a narrative hook. Davies’ interest in mental illness is fuelled by his childhood encounters with his father who suffered from mental illness and the impact of that on his childhood and family life.

Intermedial theatre offers him a means of engaging with this complex issue and allows him to layer his creative work with sensory depth and an aesthetic that encaptures the complexity of the topic. Both productions surface Davies’ preoccupation with what he calls the “layering” or “complication” of theatrical time and space and the engagement between the recorded image and the live actor.

Drawing on his studies towards a MA degree, Davies explains that similar to Les Cenci,

Les Cenci: A Story About Artaud. Photo credit Danielle Brews

“Barbe Bleue used no rational narrative progression or intelligible dialogue, a non-linear temporal structure, theatrical time that oscillated irregularly between the past, present and future, while continually jumping between spaces. In both productions, time and space were primary, advocating for narrative ambiguity and a thematic and technological throughline, rather than the primacy of narrative. Through this spatiotemporal focus, multiple points of entry were provided into the productions’ rhizomatic and at time cyclical narrative structure, encouraging the audience – in a cognitive-imaginary sense – to ‘complete’ the story. Through the depiction of recorded material shot in various exterior locations (with their own histories and meanings) that were brought into the theatre space; recorded performances of the actors projected on the cyclorama simultaneous to, or as a reflection on their live performances on stage; and the interspersion of vivid visual imagery complementing or contrasting the ideas performed/recorded, [the performance] expressed the complex intersections between past and present, exterior and interior, and virtual and visceral – an intersection where live actor and recorded body meet.”

Davies further explains that the use of recorded footage projected on the theatre’s cyclorama allowed him to manipulate the body of the performer: “I was able to dismember the body and choose to portray only a floating head, or I could multiply the body by presenting the live body adjacent to its recording. In this investigation, I also became aware of the temporal changes that were made possible through the incorporation of video. Here I could speed up an ‘uneventful’ scene or slow down the climax, or I could loop a part of the footage to replay an important action that had just occurred.” In both productions, actors speaking directly to their (own) recorded bodies or the recorded bodies of others, whilst others were also performing live, activated a spatiotemporal entanglement of spaces, time(s), bodies, actors, film/live performance and imagery that destabilised established notions of theatrical absence and presence, whilst progressing the narrative content.

In de-emphasising text, redefining theatrical space and time, mediating live performance and creating a ‘synesthetic’ theatre experience, Davies’ Les Cencei and Barbe Bleue resonate with some Artaudian ideals and offer a techno-theatrical experience that may appeal to a new generation of audiences.

Watch Davies perform in Lilith: Genesis One:

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Marié-Heleen Coetzee.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.