The Belgrade International Theater Festival was founded in 1967 and to this day represents one of the leading regional, European, and world theater festivals of new tendencies. In its rich, fifty-seven-year history, BITEF has theatrically brought together entire continents with exciting and high-quality guest appearances, concepts, and directing. Throughout history, the festival selection has included plays directed by Jerzy Marian Grotowski, productions by The Living Theatre, Shakespeare with a new perspective, Ibsen, Brecht, Beckett, and Ionesco, it also had Peter Brook as a guest. This year, the main program of the festival, in addition to two plays from the domestic repertoire, was enriched by theatre performances from Sweden, Hungary, Burkina Faso, Lithuania, Greece and Germany.

Divine Comedy. Photo by Jelena Janković

Divine Comedy through Josef Bloch: “Ego dominus tuus, Vide cor tuum”

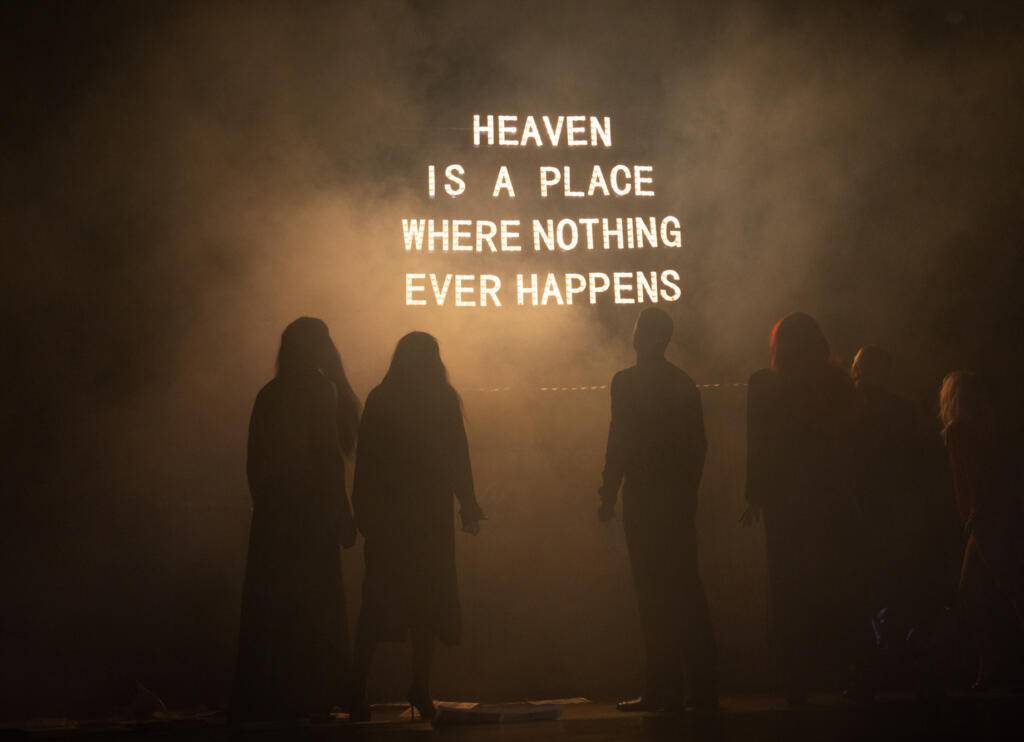

The prologue of this year’s festival was the play Divine Comedy by the Belgrade Drama Theatre, directed by the famous German director Frank Castorf. The action of unprecedented performance is based on the eponymous Renaissance literary model written by the Italian man of the new age of the Middle Ages, Dante Alighieri, and his famous mystery of the soul. Three hundred and thirty minutes of modern direction is in front of the audience. A play plays itself while a movie films in the background simultaneously. Poet, teacher, love and mercy, Dante, Virgil and Beatrice, through thirty-three cantos of hell, purgatory and paradise, take us breathlessly. The play is also Boccaccio’s experience of Dante’s work, which is why it is La Divina Commedia. Osip Mandelstam’s Conversation about Dante is also a part of the show. Above all, the stage presentation (and the film with it) follows Josef Bloch, a former goalkeeper and his hellish soul and the story told in The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick, a novel by Peter Hanke. Souls and stories within stories, in circles, are shaped in diverse and intertwined melodies from Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door by Bob Dylan to Highway to Hell by AC/DC… The place where the play (and the film in it) takes place is the city of Belgrade. Hectic traffic and old city trams, dirty parks and flashy advertisements of local retail chains and brands, scattered newspapers, the entrance to the Zvezda cinema and the Slavija hotel are realistic cinematographic shots that play from the video projector near the stage. The door closes, the lights go out, the theatre curtain rises, and the terrifying voice echoes – “Abandon all hope, those who enter.” Circles of hell become clubs. Sins and passions are numerous, colourful, and noisy – nobody is ever bored in hell. Three colours: blood-red and the contrast of black and white, stage smoke and Italian chansons and bel canto, replaced by balkanised melancholy and madness, lead us to a place of eternal shade and then, through purgatory, to the world where the blessed Beatrice awaits. Aleksandar Denić’s fantastic scenography places the audience in the metropolitan space of vice and waste, large corporations and small restaurants, rotating pinball machines and bloody refrigerators, broken telephone booths, “empty spaces”, and paradisiacal illusions. Denić’s fantastic rings and slogans constantly dynamize the atmosphere. The neon sign with the inscription “Heaven is a place where nothing ever happens” lights up the stage several times during the theatre evening. Director Castorf plays with the depth of the scene, placing in a blind spot, all the way in the back, the approach to the cold River Styx. Actors playing themselves slowly and gradually transform into roles from the ancient Roman, Renaissance and twentieth-century eras, taking on the faces of the Abyss and visitors to Eden. Throughout the entire artistic concept of the play, the acting is monitored by a cameraman and a sound engineer who live record and simultaneously broadcast the hidden direction on the screen. Joseph Bloch “dreams of acting in the theatre.” Frank Castorf enables him to do this because he introduces the dehumanization of Bloch from The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick into The Divine Comedy. With the scenes located in the tavern near the border crossing, the director alludes to the end of one and the beginning of the second sequence, like in the film by Wim Wenders, which is based on the same novel by Handke. Artistic epiphany and neo-humanism are recognised in the heavenly stanzas of Dante’s cantos. The parallels built between the languages of the past and the present, the colours of the upper and lower worlds, the play of light and darkness, the beginning and the end, technique and reality, life and art, theatre and film, intertextuality, allusions, quotations, parodies, create the renaissance of the new age, the splendour of art. Waiting for the second death in the theatre – there is a concrete city that is painful and cursed, and there is true love and wisdom sublime, in contrast: Marlboro, Coca-Cola, multinational companies; there is avant-garde, outstanding direction and a little (a lot) of soul.

Children of the Sun. Photo by Matthias Horn

Children of the Sun – Who is God laughing at?

European theatrical naturalism of our time: Children of the Sun, directed by the Slovenian director Meteja Koležnik and produced by Schauspielhaus Bochum Theatre, from Germany, violates all the laws of traditional dramatic creation. Completing another sumptuous play, the author known for directing Strindberg’s Miss Julie, a play considered by many to be the best European theatre direction in recent years, continues to stage in a new light the past era of literary classics. The dramaturgy of direction by Mateja Koležnik and the theatrology of Maksim Gorky, the stylistic elegance of the director, and the natural ruthlessness of the literary model point the finger at humanity in a small manner. They talk about the children of the darkness of a decrepit world who want to be the children of the Sun, the founders of tomorrow’s humanity. The dramatic work of Children of the Sun was written in 1905, heralding the inevitability of revolutionary changes and the Schauspielhaus Bochum from Germany, with its passionate acting troupe, with surgical precision, depicts the collapse of the old world and the harbinger of the new order, the crisis of values of both and the comprehensive social bottom – which throughout the time only changes its forms. The illusions of rich and happy drawing-room homes reveal vanity and pathology. The people who live in those “doll houses” show corruption, thievery, selfishness and manipulativeness. Set design by Raimund Orfeo Voigt and costume design by Ana Savić Gecan create both an abstract and concrete visual image of wooden figures, a harsh world and raw characters. The actors in the roles of Pavel, Yelena, Lisa, Dmitry, Boris and others are neither good nor evil. They think they are new intelligence, bearers of new ideas, creators of new science and art. They are not bound to matter – they are “free”, deprived of social restraints and easily exceed the norms of social behaviour. They think of themselves as proud, bold, strong visionaries – as opposed to weak, humble, oppressed, and unimportant. However, the latter consider the former to be useless and ridiculous and play silly games with them. The show of the crisis, dramatic and theatrical, is given through the cholera epidemic, connecting the archaic and the futuristic. The classic, even naturalistic, meticulous directorial approach makes the play extremely alternative and aesthetically intriguing. In front of the audience is a theatre of mirrors, paradoxes, infections, disasters, chaos, and the complete destruction of the world, before which both the actors and the audience can only stand, stunned and frozen, and wait for its disappearance.

Goodbye, Lindita. Photo by Theofilos Tsimas

Goodbye, Lindita – Illusion of Extinction or Eschatological Vision?

The folklore mosaic about the experience of the end is manifested through the play of the National Theatre of Greece from Athens, Goodbye, Lindita, directed by the Albanian director and actor Mario Banushi. Although this is only the second direction of the young director Banushi, it distinguishes form by its exceptional strength and an astonishing capacity for theatrical understanding, transmission and presentation of deep emotional processes within a person who finds death in front of him. The play is extremely difficult to verbalize since it describes a painful, devastating, terrifying truth of all humanity. The folklore and mysticism of the play explicitly show the ancient and other deep-rooted customs of burial in the Balkans. In the darkened room, there is a bed, a table, a television and a crying family that is facing the death of one of its members, a young woman. The entire performance is played silently, without any dialogue. Only a few muffled moans, soft sobs, and painful tremors are heard. On the stage are centuries-old traditions of Balkan posthumous rituals and funeral customs, the deepest psychological processes and ways of mourning the dead. Dramatic performance in a short time includes and combines overall religious, spiritual, emotional and artistic levels of sacred and secular Balkan traditions. In connection with the cult of the dead, the director creates a surreal theatrical stage work that translates the audience to the other side, beyond life. Ritual bathing of the deceased, dressing in wedding clothes, a living icon of the Black Madonna, the ceremony of looking into the water, falling into a trance: these are just some of the painful and shocking elements that abound in this artistic representation of dealing with the death of a family member, provoking reactions of deep sympathy in the audience. In the theatre as a primarily visual-auditory experience, the director introduces the sense of smell into his creation as a new variable. The intense smell of frankincense fills the theatre and the auditorium, creating communion and translating into the transcendental. The technique of light, or rather darkness, the gloaming of the play, the death bier in the chamber, discerned through the sparks of the night lamp and the street lantern that dimly breaks through the thin curtain of the modest home bring the unusual atmosphere. The environment is of a specific space, very intimate in the peculiar state of consciousness and mind. Time seems to stand still, and the concept of place begins to distort. The combination of pagan and Christian, cultic and religious, the perishability of material and spiritual eternity, vigil over a dead body, and burial as a wedding are just some of the motifs that are bare, executed with inarticulate painful sounds, convulsive touches and heavy smells. When the shadow of death in the play becomes too real, the terrible dream too actual, the pain unbearable, and the house empty and torn apart, a passage to the other world occurs. Each character characterized by extraordinary and suggestive stage movement becomes essential, the bearer of that unknown knowledge of another world. The minimalist funeral spectacle is strongly rhythmic, thoughtful and poignant from start to finish. It exposes and brings to the surface the repressed in each of us. The play discovers the deep subconscious in person, which shatters all the norms of life’s concepts and forceful fear. Although aware of the artistic transmission, the audience is without movement, without air – it becomes the one common soul of the entire world in facing the death of loved ones and the painful separation from them.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Emilija Kvočka.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.