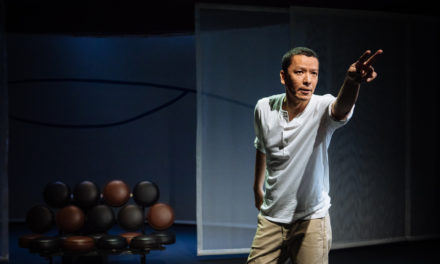

Takahiro Fujita was really looking forward to the new year in 2016. He’d already been honored when dramatist supreme Yukio Ninagawa asked him to write a play for him to direct. Now, they were each set to stage separate versions of Nina’s Cotton, that new work inspired by the life of Japan’s worldwide theater icon.

But it was not to be, as Ninagawa died, aged 80, of pneumonia on May 12.

Yet it’s almost as if some of Ninagawa’s special sparkle has rubbed off on this gifted 31-year-old playwright and director whose Romeo And Juliet—his first-ever Shakespeare production—opens soon in Tokyo.

“I’d never thought to do Shakespeare before I started to work closely with Ninagawa and began wondering why he was so obsessed with those plays,” Fujita said when we met in a rehearsal studio in downtown Tokyo last week.

As for why he chose to do Romeo And Juliet, Fujita—who founded his Mum & Gypsy company beloved by young theater-goers while he was still at university in 2007—explained:

“When I saw Ninagawa’s Romeo And Juliet two years ago, I noticed many people crying during the last scene even though they’d definitely known about the lovers’ deaths.

“So I decided to start my play with their tragic deaths and trace things back to their first encounter in the ballroom. I thought that would be a good way of examining why the tragedy came about.”

Fujita also said he primarily saw his role as trying to create something for today’s audiences.

“I regarded this play as describing teenagers’ delicate and complex emotions, which grown-ups just don’t understand,” he said.

“Actually, in the real world in Japan, there have recently been several grisly killings of teenagers by teenagers, and TV commentators are unanimous in saying they can’t understand it. So with this play, I wanted to explore complex sudden impulses such as those that teenagers can have.”

To help in illustrating youth’s fragility and vulnerability to puppy love and risky behavior, Fujita also changed Romeo to being a girl—along with other key males including his cousin, the failed peacemaker Benvolio, and his best friend, Mercutio.

“Everything happens within five days in the play,” Fujita pointed out. “So this love tragedy stems from juveniles’ impulsive actions. That’s why I didn’t want to portray a sexual love story between a man and a woman and decided to change some genders.

“In fact, I’m told that romantic fantasies and love-jealousy conflicts often happen in girls’ schools, and youths’ reckless behavior can be seen much more clearly without Romeo and Juliet’s sexual relationship.”

But he added, “Tybalt, whose killing of Mercutio set off the chain of murders and destroyed a pure girl’s world, must be acted by a man.”

Meanwhile, this Romeo And Juliet is also notable for Fujita in that, even though he has toured Japan, Europe, and South America with Mum & Gypsy, he almost always plays to theaters with 300 seats at most.

In fact, the first time he took a step up was in 2014, when he presented Hideki Noda’s 1983 work Koyubi No Omoide (Memory Of A Little Finger) at the same 800-seat Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre in Ikebukuro where he will soon do Romeo And Juliet—a mixed experience of which he recalled,

“Though I did my best, there were many points I needed to improve, so I have prepared extra carefully for this second attempt.”

For example, he held an open audition and picked 12 female cast members from about 500 candidates including amateur dramatists, dancers and models as well as the famous actress Ellie Toyota (who will play Juliet).

“I also chose people suitable for that large theater,” he said, “and I strongly urge producers to give promising directors more chance to develop their skills by working at big venues.

Finally, Fujita stressed that this Romeo And Juliet aims to broaden any fixed ideas audiences may have about Shakespeare as well as providing something to break the routine expectations of their cultural lives

“While people can do almost everything at home while facing a screen, theater can provide something beyond a high-tech, life on convenience,” he said. “But I’m talking about really good theater that doesn’t just depend on gorgeous sets or celebrity actors, and day by day I’m trying to get more people to understand that true value of theater.”

Let’s hope Ninagawa is somewhere listening to Fujita, and seeing the sparkle in his eyes, too.

This post originally appeared on The Japan Times on November 22, 2016, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Nobuko Tanaka.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.