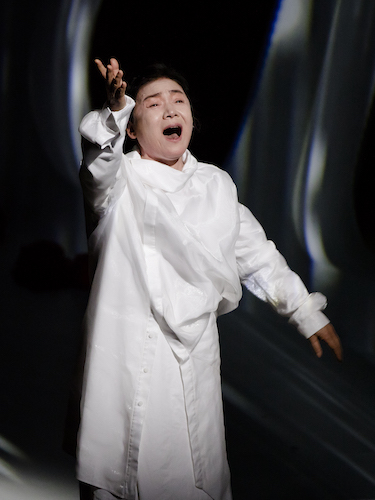

Euripides’ play Trojan Women has been adapted and performed numerous times around the world, from a version written by Jean-Paul Sartre to American playwright Charles Mee’s 2003 adaptation that included Holocaust and Hiroshima testimonials. This time, it has been given a Korean pansori makeover by SIFA Festival Director and Cultural Medallion winner Ong Keng Sen in a collaboration with the National Theatre of Korea and performed at Victoria Theatre, Singapore. Ong conceived and directed this luminous and mesmerizing Korean opera while the pansori was composed by Korean “living cultural asset,” Ahn Sook-Sun (pictured below), with music composed by Jung Jae Il.

Ahn Sook-Sun as Soul of Souls, Trojan Women. Photo courtesy of National Theatre of Korea.

Pansori, a Korean folk musical storytelling tradition usually performed by a vocalist and a drummer, goes as far back as 17th century Joseon Korea, and out of twelve epics, only five have survived in full. Its revitalization in this global format owes a lot to the National Changgeuk Company of Korea, which breathed into it new life through its incorporation into Korean opera. While not the first Greek tragedy rendered in pansori by the National Theatre of Korea, nor even the first time Trojan Women has been sung in pansori for an international audience, many of the elements of pansori–its use of traditional instruments like buk, the Korean traditional drum, and gayageum, the Korean zither, its irregular rhythms to reflect abysmal emotional states, the husky vocal timbre of the wail in narrative singing–make it well-suited for Greek tragedy, and puts me in mind of African-American sorrow songs, allowing for the pure and deep expression of pain and sorrow.

An elegy of pure anguish is precisely what this performance of Trojan Women delivered, helmed by the indomitable mighty voice of Kim Kum-mi as Hecuba, the Queen of Troy. The opera opens with eight women in white, their costumes resembling sack-cloth (pictured below; as the play unfolds, the costumes blur the distinction between wedding and death shrouds). The women hold red balls of yarn (possibly signifying rivers of blood). They stand amidst the backdrop of a white cathedral-like structure (to symbolize the ruins of Troy), as they await their fates to be carted off as slaves.

The opera, as conceived and directed by Ong, stays structurally faithful to Euripides’ version which focused predominantly on the women of Troy lamenting the Trojan War following Helen’s elopement with Paris (or abduction, more below). This performance also takes up the anti-war mantle originally contemplated by Euripides and is influenced by Sartre’s more contemporary adaptation in 1967. Thus, in threading this message further through the frame of the 21st century, the allegorical nature of this changgeuk demands that we look back in time, at the 20th century “theatre” of conflicts Sartre had referenced, as well as the devastations of war Euripides had been stricken by, particularly the enslavement of women and children during the Peloponnesian War (434 – 404 BCE).

Opening Scene (September 9), Trojan Women. Photo by Elaine Chiew

The allegory goes deeper though than sketching out the ravages of war. The feminist commentary here on wartime sexual violence and Western hegemony is especially acute within the context of Korean comfort women and Korean political history, particularly the Korean War. Being made the “whore” of war is movingly sung by Cassandra (forced to be Agamemnon’s concubine), whose noteworthy performance was enhanced by her pathos-filled facial expressions (pictured below), while the pain of separation writ large is sung by Andromache, heartrendingly forced to surrender her baby son Astyanax.

Hecuba with Cassandra, Trojan Women. Photo courtesy of National Theatre of Korea.

The sheer technical ability of the chorus of Trojan Women was euphoria for the ears (although Hecuba sounded understandably less energetic in the first third after three nights of unrelenting outpour but really delivered with wracked gusto at the end)

There are three men-as-men in the performance: weak-willed instigator of the Trojan War, King Menelaus; the humane Greek soldier Talthybios (despite his depraved official duty of having to kill Astyanax by throwing him from the high tower); and the Soul of Souls, the sage voice of Omniscience, all commendably performed. The casting of Kim Jun-soo as a male or at least androgynous, Helen is interesting: Helen is vilified on stage as a “bitch” and “harlot” for deserting Troy with her lover Paris (although in history, her image is more ambiguous, with Renaissance painter Tintoretto even depicting it as a “rape.”) Director Ong Keng Sen addresses Helen’s casting in his program notes: “From the beginning, I felt that the outsider role of Helen, who stands between the Greeks and the Trojans, is a character on the border.” Helen’s liminality, bolstered by the oxymoron of whether she is a “willing captive” and the fact that her voice is “between man and woman,” adds an ironic layer to the performance. In a counterpoint to Astyanax perhaps, Paris, Hecuba’s son, returns from the dead on piano accompaniment (pictured below), superimposing a time-inversion that is yet within the spirit of Euripides’ play, hints at the underlying animosity between the two women Helen and Hecuba, and signifies the cycle of our preoccupation with war over millennia.

What has stayed particularly memorable is the haunting lilt of the lone flute in moments of the pansori, and the emotional caw of vistas of sung dirge notes. The pain of being a woman has never been this raw and visceral.

Jung Jae Il as Paris, Trojan Women. Photo courtesy of National Theatre of Korea.

This article was originally published in Arts Equator on September 14, 2017, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Elaine Chiew.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.