The glass pavilions that appeared on Teatralnaya Square after the reconstruction of the Bolshoi Theatre have been hung for several years with photos of contemporary performances, presenting the theatre’s current repertoire. But the people assembled for the premiere of Nureyev didn’t see these photos—this audience was met by black and white shots of the “legends of the Bolshoi,” of the dancers who were working in Moscow back in the 1960s, when Rudolf Khametovich Nureyev was flying across the stages of Europe. “We had great dancers! We have a great history!” these posters seemed to cry. You did have great dancers, and you do; no one would argue with that. But what did you do with them, my friends? thinks the audience member hurrying to the theatre’s fenced-off entrance as he looks at the photograph of, for instance, Māris Liepa. In what sort of bleak ugliness did these artists waste their lives (ah, the ballets The Little Prince and The Wooden Prince, leading to the backstage joke that no one knows which is better, small or wooden). Sometimes they came by great roles—but Nureyev, having defected, leaping across the barriers at Le Bourget Airport, received ten times the opportunities and tried all that he wanted to try in dance, without having to coordinate his premieres with the Party. This exhibit, intended to appease the veterans of the Bolshoi (those who have been raising a fuss for a year—Putting on a show about a foreign dancer, they say; where is the one about our own dancers?) actually confirmed the fact: he was right to leave. Absolutely right.

Nureyev is director Kirill Serebrennikov and choreographer Yuri Possokhov’s second joint project, as well as their second collaboration with composer Ilya Demutsky. The first was A Hero Of Our Time—a ballet that came out in June 2015, received ten Golden Mask nominations and won three of them: Best Show, Best Work by a Composer, and Best Work by a Lighting Artist. In the successful, precisely planned, skillfully designed Hero, the choreographer and director were still, so to speak, trying on each other’s work for size, and there were times in this ballet when it felt as if one member of the pair was stealing the spotlight. This problem isn’t present in Nureyev—the entire ballet is constructed in dialogue between the director and the choreographer. It is as if the monstrous external world (where the court, on principle, doesn’t listen to lawyers) has affected the inner, theatrical world, and people have become more attentive to each other.

The show begins with an auction: Nureyev’s property is being sold off following his death. The gavel marks the sale of costumes, a school workbook, an island in the Mediterranean Sea, and photographs—some by famous photographers, some personal, the kind in which it matters not who took the picture but who is smiling at the camera. This auction frame is not a new one—one of the most famous ballets of the twentieth century, John Neumeier’s La Dame Aux Camélias, ends with an auction; there Armand Duval reminisces about his romance with Marguerite Gautier as her property is sold (the ballet, which first premiered in Stuttgart in 1978, is now part of the Bolshoi’s repertoire). But the frame is merely a frame; more important is what’s inside it.

The direction begins conversing with the choreography from the very first scene of the show. In the “anacrusis,” where the auction begins, some balletic characters suddenly, distinctly appear amidst the agitated crowd of buyers—a respectable lady ecstatically throws up her hands in clear recollection of her acquaintanceship with Rudy, and the general movement of the crowd becomes subject to a single inner music. The first scene—in the Vaganova Academy, where Nureyev trained—instantly shows the state of affairs. In the show, Possokhov speaks of ballet like a miracle (no matter how pompous it sounds, only a ballet-miracle has the right to exist; without transcendence, the cost to a human life is too great) or a myth, whereas Serebrennikov investigates how miracles and myths clash with the concrete wall of reality—and sometimes break through it.

Nureyev, dir. Kirill Serebrennikov, Bolshoi Theatre, Moscow, December 2017. Photo copyright: Mikhail Logvinov, Bolshoi Theatre.

And here is our miracle and myth: a class at the Vaganova Academy. It is a space of promise. Possokhov makes this class into a scene of surreal beauty, where the usual classical exercises are suddenly recombined into a poem of possibilities. This is not what really went on back then in Russian ballet schools—developing artists were not taught to be so free with their bodies, and if someone had turned his hip as liberally as do the dancers in this show, he would more likely than not have been investigated by the Komsomol. But Possokhov—who studied at the Moscow Academy of Choreography, was an outstanding soloist at the Bolshoi even with the sparse repertoire of the time, and then moved to the United States and became one of the freest, most inventive choreographers in the world—presents the Vaganova Academy as if it were Hogwarts, a fantastical place for the upbringing of magicians. Serebrennikov, on the other hand, comments mockingly on the sublime dances: while the dancers practice in center stage, workers move upstage and change out the portraits of the rulers: first Stalin, now Khrushchev. Only the portrait of Agrippina Yakovlevna Vaganova herself, smaller than the portraits of the Secretaries, remains where it is.

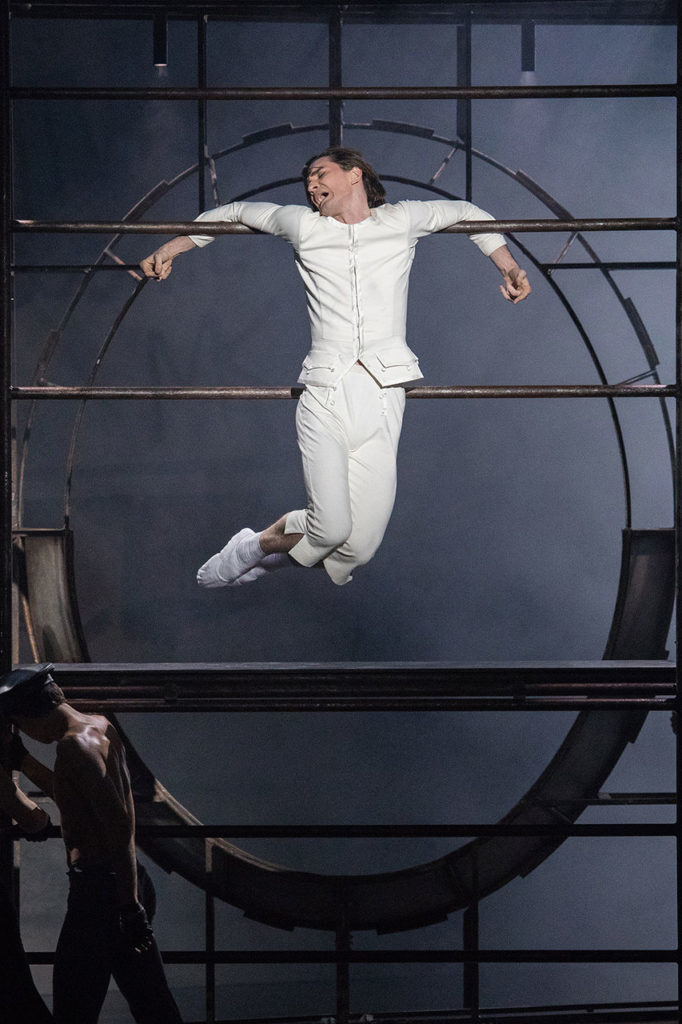

“In Paris” the direction comes to the fore when—during the reading aloud of a handler’s report on how Nureyev is behaving himself too freely on tour (for instance, walking through the city without accompaniment), that same report that caused the dancer’s flight (he hadn’t planned to leave his theatre, but when they decided to withdraw him from the tour, he understood that he would never be able to go abroad again)—the ballet troupe is found behind crowd control barriers. These are the same metal barriers that stand on Moscow’s streets on days of rallies and demonstrations, the ones that appeared outside the Bolshoi on the day of the premiere of Nureyev (obviously the administration was afraid that ballet lovers unable to obtain tickets would storm the theatre)—only here a hotel room is constructed out of them. The semi-darkness, the just-visible faces of artists sitting on the floor in the weak light behind the barriers—it is a picture that, while very simple, works flawlessly. And when Nureyev leaps across these barricades, no “airport” scenery is needed.

The strongest scenes in the show are the “letter” scenes and the two duets (Nureyev and Erik Bruhn, Nureyev and Margot Fonteyn). The “letters” are exemplary of the fusion of the directorial and the choreographic idea. Between biography episodes appear two solos—male and female. At the beginning, we hear letters written to Nureyev in our time, from artists who began dancing in the Paris Opera in the days when he reigned over it (Manuel Legris, Laurent Hilaire, Charles Jude), and the Student, a “collective” character, enters the scene. In his movements he is, of course, most similar to Legris—but Vyacheslav Lopatin, who plays this role, avoids any direct resemblance and tries to find a common, rather than a personal, style for Nureyev’s “chicks.” During the reading of the Diva’s letter (composed of correspondence from Alla Osipenko and Nataliya Makarova), Svetlana Zakharova enters—and here there is no doubt: the sharp movements, in which, all of a sudden, a slight haughtiness appears, are obviously those of Makarova. The duets, which are Possokhov’s domain, are built into the “biographical” sequence of the ballet. Nureyev’s duet with Erich Bruhn takes place in a ballet studio—his romance with the world-class Danish dancer brought our runaway not just a prolonged relationship with a calmer, more reliable, and more trustworthy person than himself, but also lessons in the detail-oriented Danish School. Nureyev began to dance more cleanly; in his performances, one can see the pas peculiar to the Danes—however, in Nureyev’s hands, this pas becomes more refined and sophisticated. (This is why Nureyev’s choreography is so difficult for Russian artists, to whom the Danish language of dance is a foreign one.) And in Possokhov and Serebrennikov’s ballet, this duet, in which Nureyev (Vladislav Lantratov) and Bruhn (Denis Savin) barely touch each other, is full of that quiet attention to another person that was rarely present in the life of the impetuous Rudy. (Here it is obligatory to make note of Denis Savin’s breathtaking work—the artist, who bears no resemblance to Bruhn in any aspect, from the color of his hair to his school, creates such a precise physical portrait of the great dancer that occasionally one flinches at the way he turns his head or moves his hand; it’s as if the long-dead Bruhn had really suddenly appeared in the Bolshoi.) The second duet (Nureyev and the English prima ballerina Margot Fonteyn) is more open and passionate: here, nothing is left to the imagination. It seems to me that there was supposed to be a little artificial theatricality here (not without reason, but as a nod to Frederick Ashton’s Marguerite And Armand), but Vladislav Lantratov and Maria Alexandrovna fling themselves into this dance with such sincere happiness that it seems as if they simplify the director’s message somewhat. This dance has authentic chemistry, but no theatricality.

Nureyev, dir. Kirill Serebrennikov, Bolshoi Theatre, Moscow, December 2017. Photo copyright: Mikhail Logvinov, Bolshoi Theatre.

The success of the finale is again shared between the two creators. This final scene is about La Bayadère, Nureyev’s last project, which he decided to conduct (at this point, he was already too unwell to dance). Possokhov takes the exit of the Shades from the last tableau of La Bayadère—an ethereal and tragic procession of girls in white tutus—and writes into Marius Petipa’s choreography male dancers, who are more or less absent in the original. In Petipa’s time—during the reign of “old ballet”—ballerinas were the only dancers who had any significance; Nureyev was one of the most important dancers of the twentieth century, which, with his help, became the century of male classical dancers. Possokhov actually does something astonishing here: while practically all the “heritage ballets,” from Swan Lake to Giselle, have already been reinterpreted in some way or another by contemporary artists (from Mats Ek to Boris Eifman), almost no one has touched La Bayadère (except, to my memory, one experiment by a small Dutch troupe). The “Shades” seemed to be untouchable; there was a sense that any change would simply ruin them. But Possokhov has built a male corps de ballet into the female one such that it is as if the men had always been there. The men here remain men (there are, God forbid, no burlesque tutus and pointe shoes), but they fit into the music and the classical walk exactly as the women do. In this way, Nureyev’s contribution to world ballet is demonstrated—and it would have been difficult to do so more precisely with words. In the meantime, the protagonist—already extremely unwell, with an unsteady gait—descends into the orchestra pit, where he takes the place of conductor Anton Grishanin and directs the Shades. Even when the music ends—clearly representing the end of Nureyev’s life—the dancers’ movement continues.

At a briefing before the premiere, the general director of the theatre, Vladimir Urin, announced that the show would be presented once again in May. Represented at the show were firms involved in the screening of ballets in movie theatres all over the world; they say that negotiations are in process. These days, the task of the theatre is to keep the show in good form, demonstrating that it is still possible to practice ballet in contemporary Russia. Well, or to say, once again, after Nureyev: Rudolf Khametovich, you were right.

Translated from the Russian by Rose FitzPatrick. This article originally appeared on the website of the Russian theatre journal Teatr. Translated and reprinted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Anna Gordeeva.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.