A hit of the Edinburgh Fringe 2017, Selina Thompson’s one-woman show salt is on at the Royal Court Upstairs in the original production but with the new performer, Rochelle Rose, replacing the author in the role of the Woman.

I did not have the privilege to see the initial highly commended performance, which emerged from intimately autobiographical material, so this revival is a strange and, seemingly, a deliberate conundrum which raises questions around authenticity, legacy, the personal and the political. The presumably new ending to the script published in 2018, explains the decision of passing on the performance to another as a task of communal sharing of grief.

In many ways, Thompson’s is an important piece of political theatre about intersectional identity politics, which surfaces some of the hitherto silenced histories of slavery and oppression. In it, she crystallizes personal family history, storytelling, memory, fantasy, political oration, poetry, humor and travel writing combined with elements of ritual and live art into a slick, finely crafted indictment of racial injustice and historical oppression. At the center of the story is her trip at the age of 26 from Belgium to Ghana and Jamaica and to the East Coast of the United States, along the Transatlantic Slave Triangle route, in search of a sense of belonging.

Diasporic struggle and the eternal loss of home – especially at the time of a major migration crisis – could be a theme that transcends the confines of a particular cultural experience, but here it is kept very specific, for rather obvious and justifiable reasons. As a result, members of those cultures not directly implicated in the histories of African slavery might feel alienated by some of the content that tends to view all international relations in the world through this very particular lens. Nevertheless, beyond this main premise of the piece, there is much else to contemplate and admire here on the level of artistry and even anthropology.

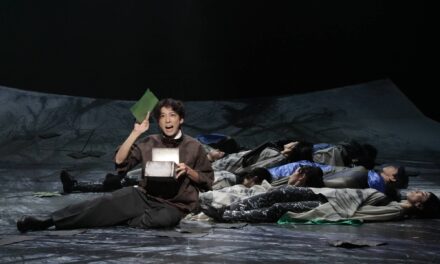

Rochelle Rose in salt. by Selina Thompson. Directed by Dawn Walton. Photo by Johan Persson.

Juxtaposed to the heritage of trans-generational trauma, is the author’s depiction of exceptionally warm, loving and healthy home life. The protagonist discloses her background as both second and third generation Jamaican, by the circumstance of being an adopted child. Unlike some artists, who might trace their sense of personal trauma to the fact of being adopted, all that is traceable in Thompson’s case in this respect is a deep sense of love, security, and connection to her adopted parents. As she travels around the world, eventually plunging into lethal depths of emotional pain, the main source of serenity and joy – and her true lifeline – are her whimsical phonecalls to her dad. In a show which is ultimately about social privilege, it might be trivial to observe how rare and precious this enviable sense of family-rooted wellbeing might seem to some. But if theatre does not offer us this kind of dialectical contradictions, then it might just end up being a political soapbox.

This piece’s main conceptual and artistic value, however, is contained in its metaphorical distillation of the artist’s lived experience as portrayed therein – traveling the ocean, transubstantiating, transforming – into a rock of pink Himalayan salt. A haunting visual leitmotif is the image of the Woman pounding the rock of salt with a large hammer – and in one sequence this becomes a means by which to illustrate the connection between the political and the personal too.

Thompson’s creation is a layered and complex one that works on many levels, giving the audience an element of choice as to how to relate to this communal experience which also requires a commitment to ‘sit with the pain’, and sends you away with a tangible keepsake. Taking on the mantle from Thompson, Rochelle Rose is eminently watchable, meticulous and enticing, but the viewer is always bound to wonder just how far removed this experience might be from the rawness of the original one.

Rochelle Rose in salt. by Selina Thompson. Directed by Dawn Walton. Photo by Johan Persson.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Duška Radosavljević.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.