It’s one hundred years since the birth of Gellu Naum, Romania’s greatest Surrealist poet. Two recent London events notably marked this centenary: N(aum), a play brought from the Romanian stage to the Leicester Square Theatre, and Gellu Naum: The Incendiary Wanderer, an evening of readings and discussions at the Romanian Cultural Institute.

Gellu Naum, born in 1915, studied Philosophy in Bucharest and soon joined the literary avant-garde. His first book of poems, The Incendiary Traveller was published in 1936. Two years later, in Paris, he met Andre Breton, founder of French Surrealism, and on his return to Romania, himself began the Romanian Surrealist Group. Before the war, he published prolifically – poems, plays, and prose – but afterward, with the imposition of Socialist Realism as the only accepted literary form, the Surrealist group disintegrated. Naum, left silent and stranded, continued as the last remaining Surrealist in the country. To survive, he made translations and wrote children’s books: Apolodor – his tale of a little Penguin’s quest for its home – is now a children’s classic. Later, in 1968, when a cultural liberalization began, Naum once again began to produce prose and poetry, publishing in 1985, his novel Zenobia, which, alongside Breton’s Nadja (1928), is one of the finest examples of a Surrealist work. Internationally fêted, Naum died in Bucharest in 2001.

N(aum), the theatrical work is recently seen in London, is a Surrealist play par excellence. Oana Pellea and Cristina Casian – under the direction of Mariana Camarasean – here find the very essence of the Naumian universe.

On an almost barren stage, a suitcase vibrates under the saccadic roar of a train: it’s the beginning of a journey. The travelers, played by Pellea and Casian, are clad in men’s coats and hats. There is no sense of time, and no obvious relationship between the two: it’s a ‘chance’ Surrealist encounter, that can mean nothing or everything: on a journey, after all, any companion is a good companion. The text surprisingly isn’t taken from or inspired by the plays Naum wrote but is made up of fragments from his writings – in prose, interviews, things he said or which were said about him. It follows the Surrealist codebook, where disparate fragments, like the images in a dream, unveil, with no obvious plot. The everyday (the reading of a book, an exchange of pleasantries) meets the extraordinary: did we know that “within us, there are castles, fields with blue and yellow flowers?” In an apparently monotonous and monochrome world, a lot is happening.

Gellu Naum (1915-2001)

“We have been witnessing the death of love for millennia,” says Pellea’s character, and at once these words concern us. Are we just observers of this journey or active participants? It’s good to know, either way. We’re not doing the hard work – Naum did it for us – but we’re privileged to reap the benefits, should we choose to.

Watching Oana Pellea is an event in itself. One of Romania’s best-loved actresses, with an extensive theatre and movie career both at home and abroad, she’s as fresh and daring as ever. It’s that particular melange of childlike curiosity, light, and humility that allows her to own Naum’s words. And these words do come, beautiful and discordant, poetic and puzzling. This is not traveling light.

Pellea’s stage partner, Cristina Casian, is a worthy companion: juggling words, incarnating memories and providing a resounding echo to Pellea’s character.

Words, more words, light, shadow and the voice of an angel:

“Shed your aging skins!”

“Why do I have to make this journey?” Pellea asks.

“So you can meet yourself!” the angel answers.

If we’re left with anything beyond the experience of fine acting and Naum’s writing, it’s the urge to see life the Surrealist way. To find the extraordinary in the ordinary, to shed ‘the aging skins’ of “reality” and to turn inwards. This, one suspects, is how Naum reached the self: N(aum) is a journey that goes full circle, ourselves the beginning and end of it. It’s reserved for the seers and those who still search and refuse to take things at face value.

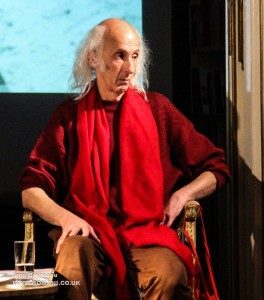

Stephen Watts – image by Inno Brezeanu

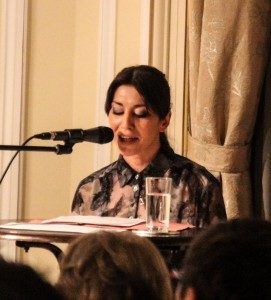

The Gellu Naum evening a few days later at the ICR had an appealing format: starting with the viewing of an exhibition of Naum’s life and work, followed by special guests shedding light on his oeuvre and its relevance today, and ending with a glass of Romanian wine. The talk, coordinated by the ICR president Dorian Branea, had as guests the writer and poet Simona Popescu – a friend and confidante of Naum’s – as well as Naum scholar and translator, the Scottish poet Stephen Watts, and acclaimed actress Andreea Paduraru, reciting a selection of poems.

Simona Popescu told us that Naum was first and foremost a Surrealist and only then a writer: “To the Surrealists, Surrealism was a way of life and their work an incidental consequence.” Certainly, Naum was something of a mythological figure too: an intimidating presence, an oddity with an ordinary existence. In his own words, taken from The Incendiary Traveller, he “Could be a priest or a tie/He is an autonomous forest.”

The ICR guests argued for Naum’s relevance and took turns with Andreea Paduraru, who filled the room with Naum’s words: “Never were we so far away from each other / By simply applying the rational” (from the poem Oh, So Many Things Are Happening). For Naum, according to Simona Popescu, “There are some who see / Others who search” – he lifts the blinding veil of reality off our eyes. Simona Popescu recounted a parable Naum once told her: “You cannot see the mountains from Bucharest but still, there are some perfectly clear summer days when the mountains show up. I have seen them.” Naum, as Stephen Watts put it, is “in the earth and above the earth.”

Andreea Paduraru–image by Inno Brezeanu

Naum’s poetry is not for the faint-hearted. It requires a leap of faith from the reader who must renounce expectations and preconceived notions of what poetry should be. Only then, one might say, does Naum reveal himself. Now, as we are being slowly devoured by consumerism and the lust for immediate gratification, Naum is both an anchor to keep us grounded and the wings to something bigger and more substantial than any visible reality: he is vital.

This article originally appeared in Central and Eastern European London Review on November 5, 2015, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Camelia Ciobanu.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.