Montreal, Québec

Kelann Currie-Williams reviews Sermo Scomber Theatre‘s Don’t Read The Comments in the Montreal Fringe Festival

World Premiere of Sarah Segal-Lazar’s Don’t Read The Comments (Sermo Scomber Theatre), at the St. Ambroise Montreal Fringe Festival 2018.

Dakota Jamal Wellman, Cara Krisman, Joy Ross-Jones & Gabe Maharjan in Don’t Read The Comments. Photo by Zoe Roux.

In Sarah Segal-Lazar new play Don’t Read The Comments, the question of the existence of a grey area, or of blurred lines in the context of consent and sexual encounters, is explored through a comically exaggerated bouffon style. Formatted as the live taping of a talk show bearing the play’s same title, Don’t Read The Comments and its host Wendy Winfrey (a hybridized version of Oprah and Wendy Williams, with occasional hints of RuPaul, played by the exceptionally talented Dakota Jamal Wellman), address the audience and demand our participation in the conversation. With very little warning as to what we are about to see, Winfrey invites three guests onto her show: Grace Haverford, a more-raging-than-radical feminist (Cara Krisman); Geoffrey “Tripp” Jeffrey, a self-proclaimed male feminist and YouTuber (Gabe Maharjan); and Cindy Nancy Cindy, a Centrist politician (Joy Ross-Jones) who is clearly on the wrong side of the conversation on sexual consent.

Don’t Read The Comments uses bouffon to express a spectrum of difficult topics; examples include themed segments such as “Act it Out!” and question-driven conversations which touch on topics of consent and often culminate in characters going on loud, unprompted rants or excessively touching each other. In one memorable scene host, Wendy Winfrey prompts her guests to race towards her and adjust their speed by reading aspects of her body language–a challenge Grace Haverford wins by not approaching Wendy and instead, taking a seat while her two opponents ceaselessly push each other aside in pursuit of first place. A similar tone is struck in the play’s most explicitly sexual moment when guest Grace Haverford suggests that every and all sexual encounters should be prefaced by the signing of a contract between both parties because, as she says, “What could be sexier than that?” As both Haverford and Tripp attempt to “act out” the signing of one such contract with what can only be described as a phallic balloon pen, their stiff demonstration progresses into a cacophony of moans and unbridled touching–an interesting climax to the live show’s most graphic segment.

Prior to the exit of the live show’s three guests, male-feminist Tripp is accused of sexual assault. This declaration, announced by Wendy in a chillingly-upbeat manner, slightly alters the play’s overall narrative. Clearly shaken by the news, Tripp begins panicking and angrily stumbling around for a line of defense. He comes to the conclusion that because both he and his accuser were drunk when it happened, he was also a “#survivor.” Tripp’s statement is soon followed by temporal shift set into motion by the host Wendy: she sends the guests back in time by literally having them move backwards as a means to reset and restart the segment.

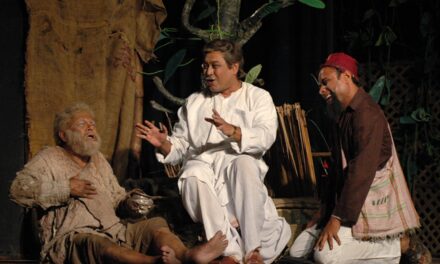

Cara Krisman, Gabe Maharjan, Joy Ross-Jones & Dakota Jamal Wellman in Don’t Read The Comments. Photo by Zoe Roux.

It is difficult to look at show’s three guests. Not simply because of their larger-than-life clown-like costumes and makeup and extravagant physical acting, but primarily because of the realness with which they speak. What is most disturbing is the potential of the guests’ seemingly hyperbolic and farcical personal stories about sexual encounters (and allyship in the case of Geoffrey “Tripp” Jeffrey) being perhaps not that exaggerated. Under the thick layers of clown makeup, padding, and vibrant clothing, the interactions between the play’s clownish characters (or perhaps, more aptly, caricatures) are striking. In almost every word they say, you realize just how commonplace their opinions are. You realize how often you have either read phrases like these online, heard them in interviews, or listened to them uttered while in conversation with someone.

After roughly 40 minutes of host Wendy Winfrey asking her guests uncensored questions, she ushers her three guests off stage and invites her next guest “Tanya” (played by the show’s writer Sarah Segal-Lazar) onto the fictional show. In this moment, you hope to yourself that her presence will bring about some temporary relief from the bombardment of sexual innuendoes, in-your-face bouffon, and hashtagging of every and any term that could benefit the character’s opinion. While we do receive some relief, it is short-lived, as Segal-Lazar’s nearly 20-minute monologue soon takes the form of a chillingly poignant retelling of experiencing a forceful sexual encounter while abroad in Ireland. Before she is able to end her story on her own terms, host Wendy interrupts and shoos Segal-Lazar off-stage. With the show back in her control, Wendy ends the performance by asking the audience whether the story was an instance of a non-consensual sexual encounter; she invites them to respond by choosing one of three cards: “yes,” “no,” or a single question mark.

The transition from bouffon style to naturalistic and earnest monologue is surprising and effective. The grotesque, cringe-worthy, and powerful performances given by the live show’s three guests are continued in Segal-Lazar monologue’s–albeit with less screaming, a noticeable lack of clown-like clothing, and considerably less physical contact. Her calm retelling is startling and at times distressing. How can a story that is so clearly an instance of an unwanted sexual encounter be shared with such an even tone and temper? At times I found myself unable to look at her, in an echo of the way I turned away from the talk show’s guests and host, moved to do so because of being overwhelmed by something paradoxically common. To my surprise, the over-exaggeration of the bouffon proves to engender similar emotions as the sincere and deeply troubling monologue. Segal-Lazar seems to have created a perfect marriage between the two styles.

Much like the rewinding device which resets and restarts certain aspects of the performance, Don’t Read The Comments explores the desire to go back to the time before the unwanted compliment, the subtle yet unsolicited touching, and the non-consensual sexual encounter that should have never happened. Across its two distinct styles, Don’t Read The Comments tackles the conversation about sexual consent, pressure, and assault in an engaging, effective, and thought-provoking fashion. As a performance, it does not hold back in its effort to make clear the supposedly “blurred lines” of sexual consent. As an experience, it left me a little more than uncomfortable. But maybe we should never get too comfortable when talking about sexual consent.

This article originally appeared on alt.theatre on June 26, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Leah Jane Esau.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.