August 7 marks the 80th anniversary of the death of Konstantin Stanislavsky (1938–2018). As a tribute to the great Russian master, the Russian Theatre course at the University of Macerata ended with a reading of Remembering Stanislavsky (June 12, 2018). A student group of 18 young women rediscovered the most important moments of his existence and his long artistic career: the founding of the Moscow Art Theatre, the staging of Chekhovian masterpieces, the American tour in 1923–24 and the international glory of his system of acting.

All over the world, the name “Stanislavsky” immediately recalls the great father of the art of directing. But Stanislavsky is also a great master of inner research, and his lesson is immense in art and life because the creative gesture can transmit an emotion only when it is the result of achieving individual awareness.

There is no practice without theory. In the age of talent shows and cultural improvisations, Stanislavsky’s heritage is very important to transmitting high values and rigorous discipline to young people, without the anxiety of protagonism and the fever of visibility. For these reasons, the reading–in three sessions with a thematic and historical structure–offered each woman equal creative space for a personal performance.

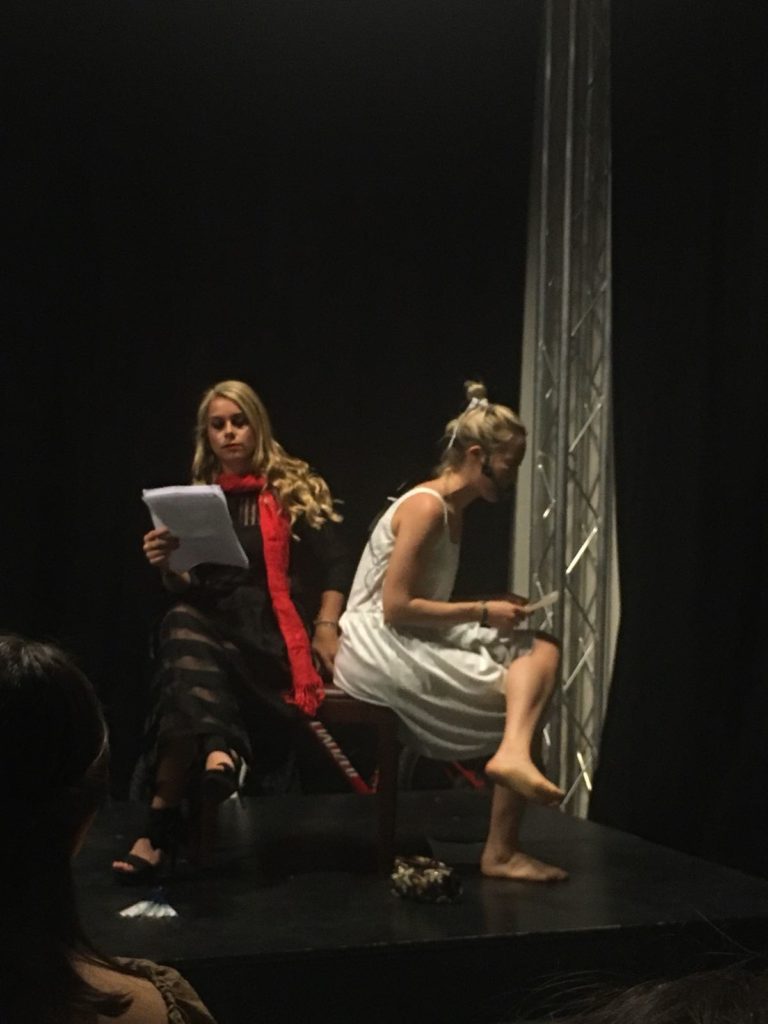

Remembering Stanislavsky, University of Macerata, June 12, 2018. Press photo.

Moreover, each woman had freely chosen the character to voice the feelings. It was a spontaneous decision, without any imposition or pressure. In fact, Stanislavsky’s basic rule for individual harmony is the authenticity of knowing ourselves: in this way, all the roles of the reading were the result of personal research into–and reflection on–the art and the life of the great Russian master, considering also some of the most important plays of theatre history.

Remembering Stanislavsky, University of Macerata, June 12, 2018. Press photo.

Each woman wrote a short dramaturgy which was an inner monologue of the chosen character, defining also the costume and makeup: in the first session, the voice of Stanislavsky (from his autobiography My Life In Art) was linked to the memories of Nemirovich-Danchenko and the prose of Bulgakov (from Theatrical Novel). In the second session, there was a gallery of Chekhovian women: Nina and Arkadina (The Seagull), Elena and Sonya (Uncle Vanya), the triad Irina-Olga-Masha (Three Sisters), and Ranevskaya and Anya (The Cherry Orchard). Each represents a different aspect of the complex and fascinating female universe of Stanislavsky’s staging: the comparison between a young actress and a diva, the possible friendship between stepmother and stepdaughter, the mutual love among sisters, the relationship between mother and daughter.

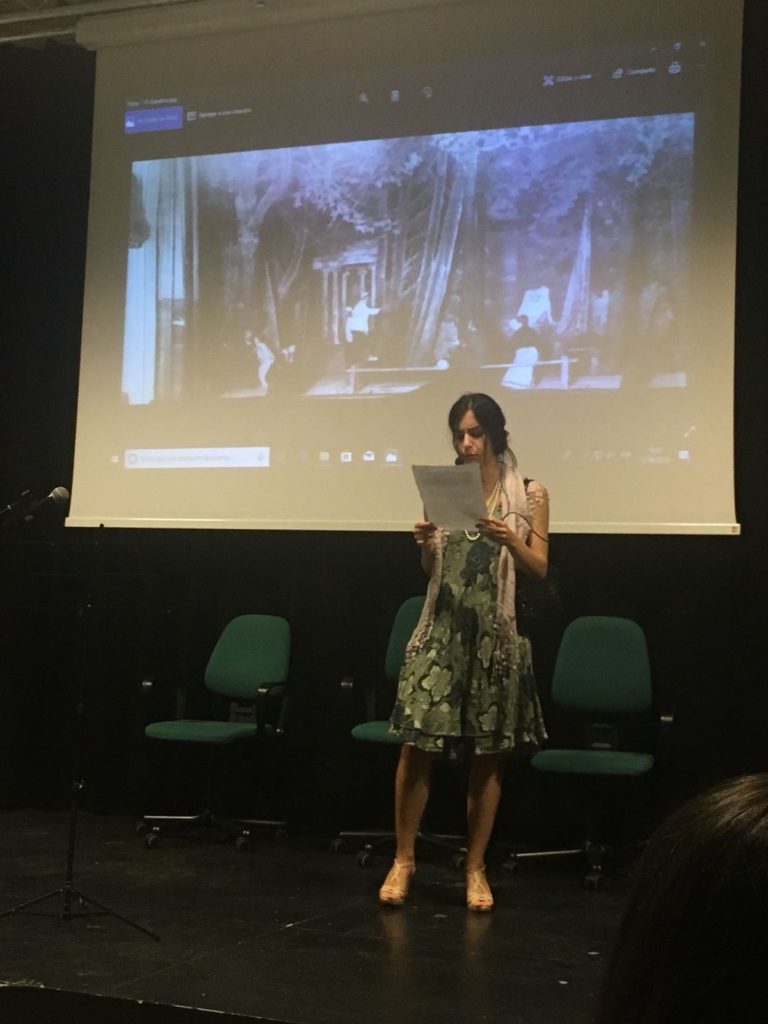

Remembering Stanislavsky, University of Macerata, June 12, 2018. Press photo.

The third session presented the relevant moments of Stanislavsky’s tour in the United States: his last meeting with Eleonora Duse and her Ibsenian role of Ellida (from the play The Lady From The Sea), his work on Dostoevsky’s great inquisitor (from the novel The Brothers Karamazov) and Goldoni’s Mirandolina (from the comedy The Mistress Of The Inn).

In the finale, there is also an homage to an Italian playwright appreciated by Stanislavsky: Gabriele D’Annunzio, who died on March 1, 1938, a few months before the Russian master. In fact, the virtual scenography of this reading recalls some precious photos from the books on Stanislavsky and the Moscow Art Theatre held by D’Annunzio in his private library at the Vittoriale, in Gardone Riviera.

After a rewriting set in the new millennium of some scenes from Act II of the play La Figlia Di Iorio (The Daughter Of Iorio), when the lovers Aligi and Mila started to live together, an exercise was offered that Stanislavsky would define as for the “creative imagination,” based on the famous poem La Pioggia Nel Pineto (The Rain In The Pinewood).

For all the participants, this reading was a deep human experience. It underlined the immense value of Stanislavsky’s heritage, also in a student context. After 80 years, his figure remains a guide for worldwide theatre, and his memory is truly worthy of celebrating.

Remembering Stanislavsky, University of Macerata, June 12, 2018. Press photo.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Maria Pia Pagani.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.