Andrzej Wajda, the internationally renowned Polish film and theatre director and icon of the “Polish School” of filmmaking, passed away in Warsaw on October 9, 2016 at the age of 90.

Wajda’s more than 60-year career began with degrees in painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków and in directing from the Łódź Film School. He began these studies after World War II, during which he fought in the Home Army of the Polish underground resistance to Nazi occupation. His first film, A Generation (1955), is a coming-of-age story set in Warsaw against this very backdrop. Like this one, many of the numerous film and theatre productions that Wajda would ultimately direct engaged with contemporary Polish history—often, events that the artist himself lived through. He also took up great works of Polish and European drama and literature, from Adam Mickiewicz and Tadeusz Różewicz to Dostoyevsky and Shakespeare.

Andrzej Wajda at a press conference for his film Wałęsa: Man of Hope (Wałęsa: Czlowiek z nadziei, 2013). Photo credit: Kacper Pempel

Wajda’s films, which brought fame to Polish actors like Zbigniew Cybulski and Krystyna Janda, received major international prizes. Man of Iron (Człowiek z marmuru, 1981), about the growth of the coincident Polish Solidarity movement, won the Cannes Palme d’Or that year. Four of Wajda’s films were also nominated for the Oscar in the Best Foreign Language Film category, and he won the Academy Award for Lifetime Achievement in the year 2000. Long fascinated by the art and theatre of Japan, Wajda also received the Kyoto Prize, that country’s equivalent of the Nobel, in 1987—and donated the funds to build a new home for Japanese art in Kraków, the Manggha Museum of Japanese Art and Technology. Wajda was also recognized with honorary doctorates from several universities in Poland and the United States, and he later founded the Wajda Film School and Wajda Studio in Warsaw, together with the director and screenwriter Wojciech Marczewski.

Throughout his career, Wajda directed more than 40 productions at important theatres in Poland and abroad. For many years, he worked at the Stary Theatre in Kraków, after his 1963 production there of Stanisław Wyspiański’s The Wedding—an iconic Polish drama that, like several of his other works for the stage, Wajda later made into a film. In his theatre productions, the artist frequently took experimental approaches to casting and design, exemplified by his 1989 production of Hamlet. For this production, he cast Teresa Budzisz-Krzyżanowska, a Polish actress famed for her performances of classical roles, as Prince Hamlet. The play began in a dressing-room area at the Stary, allowing the audience to witness her transformation into this role—which the actress herself pushed Wajda to allow her to play not as a man, but as a performer, as herself.

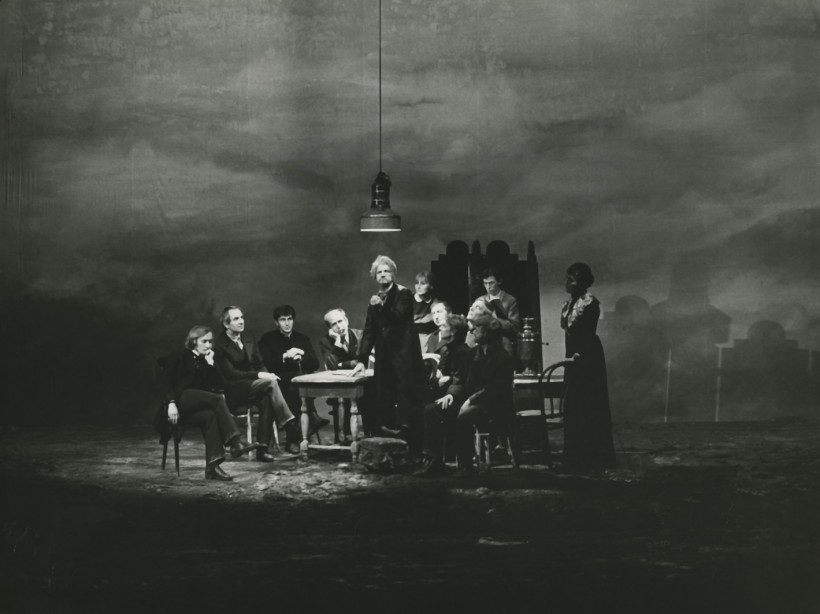

Among many notable performances of Polish texts, Wajda staged others by international writers, ranging from Sophocles to David William Rabe or Antonio Buero Vallejo. Wajda was especially known for his own adaptation of Dostoyevsky’s The Possessed (Biesy, 1971), which played for 13 years to sold-out houses at the Stary. It was also produced at Yale Repertory Theatre in the United States in 1974, with a cast that included a young Meryl Streep. In 2013, Wajda released The Possessed Years Later, a film about this production and the process of its creation.

The Possessed (1971), dir. Andrzej Wajda; Stary Teatr, Kraków. Photo credit: Wojciech Plewiński

In his 1998 autobiography Double Vision (Podwójne spojrzenie), Wajda wrote:

I am often asked why I work in the theatre, though its achievements disappear in time and are so easily forgotten, when I have the opportunity to make films, which are lasting and stay for ever, having the chance to amuse and affect future generations? Well, it is exactly this transitory and ephemeral character of the theatre which I feel deeply and truly drawn to. There are other natural needs of man apart from the search for immortality and the will to survive; we are also attracted by death and nothingness, the more, the older we get.

The book’s title derives from Wajda’s conviction about the film director’s “two eyes”: “one to look into the camera, the other to observe intently everything that is going on around him.”

In 2007, Wajda created the Oscar-nominated film Katyń, which dealt with the mass execution of an estimated more than 20,000 Polish citizens—prisoners of war and others—by the Soviet secret police in 1940. One of the victims of this tragedy was Wajda’s father, Jakub Wajda, an army officer. The artist’s last film, Afterimage, premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival this year, only a week before Wadja’s own passing. In a reflection of Wajda’s artistic and political values, the film’s subject is the avant-garde interwar painter Władysław Strzemiński, born in Minsk and a founder of Blok Constructivism in Poland—where, as an artist and teacher, he opposed Stalinism and the state-mandated aesthetic of Socialist Realism.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Lauren Dubowski.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.