“Theatre is the art of looking at ourselves” – Augusto Boal, founder of the Theatre of the Oppressed.

The performance took place on a makeshift open-air stage using only simple props, under the roof of a traditional Javanese theatre. The pendopo, as it is known, forms part of a sub-district office in Sleman, on the outskirts of Yogyakarta. The performers were a diverse group, including teachers, traders, activists, housewives and unemployed dependents. They all had different backgrounds, characters, needs, and aspirations. Prior to the production, the one thing they all shared was participating in research conducted by Ekawati Liu, a Ph.D. candidate from Deakin University in Australia. The study focused on the livelihood choices of Indonesian villagers with disabilities.

The first act involved villagers with hearing impairments describing their difficulties in accessing effective hearing aids and other equipment. They described to the audience how this affected their ability to participate in their local community. The second act portrayed the story of a young man raising chickens who needed a loan to expand his business. When the financial institution’s field officers visited to inspect his business, they learned that he was blind. Without ever referring to his disability, the field officers found excuses to refuse the loan. The man has found no resolution, leaving the audience to question how society could better support people with disabilities.

The discussion after the performance added a third act, expanding to include the audience. It was asking them to participate in deciding how the story would unfold, not on the stage but in their real lives. Many in the audience had their own experience in lacking the facilities they needed to participate fully in community life. It took effort and energy for many of them as they had conditions that made communication challenging. Sign language interpreters were available to expand participation in the forum. Everyone made the effort, and those expressing their opinion felt confident that when they spoke, they would be listened to.

The Project

The performance and following discussion were the results of a project organized by the Peduli Program. It brought together a group of villagers with wide-ranging and diverse disabilities from the surrounding areas of Kulon Prujo and Sleman to identify issues of concern to disabled people and to discuss solutions. In Indonesia people with disabilities often refer to themselves as “difabled,” derived from the English term “differently abled.” The project focused on giving participants an opportunity to express their frustrations and hopes through performance.

Photo credit Irfan Kortschak

The program included a five-day workshop held at the Institute for Integration and Advocacy of the Difabled (SIGAB – Sasana Integrasi dan Advokasi Difabel), an independent non-government organization established in 2003 to defend and fight for the rights of the difabled throughout Indonesia. The workshop was facilitated by Joned Suryatmoko, a theatre-maker, playwright, community facilitator and researcher, whose role was to manage the logistics of the process and to establish a framework for the participants to explore and express their experiences while allowing them autonomy to shape their own performance.

Joned was clearly influenced by the ideas of Paulo Freire and Augusto Boal, founders of the Theatre of the Oppressed, a theatrical form originally used in radical popular education movements. He believed that all members of the community, including those with no formal training or experience as artists, have the agency to transform their own knowledge into aesthetic practices and art. By doing so, the performers have the power to transform both those who perform and the audience with whom they interact. Joned believes that theater is “a means of transforming society.” He says, ‘Theatre can help us build our future, rather than just waiting for it’.

Shared Interests

In order for workshop participants to produce a story reflecting their aspirations and concerns as a group, they first had to become aware of their shared interests and common concerns. This was not always obvious, as each member of the group had developed their own means for dealing with their own life. They didn’t necessarily see what they had in common with those around them.

For example, while the fiercely independent 70-year-old Muji had previously participated in village-level disabled people’s groups, he didn’t identify with the label “difabled.” Sure, he was completely blind, but he was an active professional musician. He was able to climb trees to harvest coconuts and he had worked as a masseur. He felt that he was able to support himself without charity and therefore did not consider himself difabled. It was not clear to him what he had in common with Karyati, who had previously been hospitalized and medicated for schizophrenia and had periods where she felt unable to look after herself.

For the group to find their shared story, each performer had to first reflect on her or his own personal experience and see the intersections between their story and those of the others in the group. Through a brainstorming session, they worked in small groups with a range of photos and visual prompts (which were described in detail to those with visual impairment). The participants used these prompts to define their current socio-economic circumstances, their aspirations, and the perceived obstacles to achieving these aspirations.

Developing A Common Story

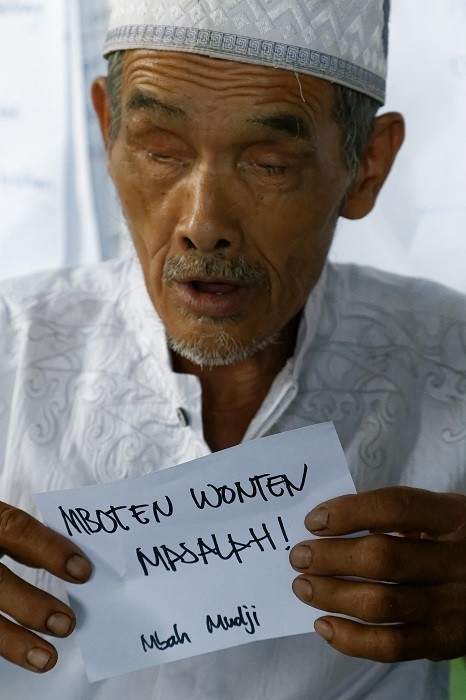

Each member of the group interpreted this task in their own way. The irascible Muji at first stubbornly insisted that he didn’t have any problems (“Mboten wonten masalah!”). Others concentrated on their aspirations, with one hearing-impaired man stating simply, “Aku ingin punya pekerjaan” – “I want to work.” Some focused on their own attitudes and lack of belief in themselves. Dian, an extroverted activist with reduced mobility due to polio, stated that the problem was that other people didn’t believe she could be a useful member of the community (“kurangnya kepercayaan”). Others focused on the practical equipment and facilities they needed, particularly assistive devices such as hearing aids and wheelchairs.

Each participant wrote down a simple phrase, short sentence, or a single word on a piece of paper to summarise the aspiration or constraint they had identified. In small groups, the participants discussed and explained the reasons for their choices. Participants began to see how the ideas of other participants related to them. For example, after hearing others talk about their need for assistive devices, Muji started making connections between others’ experiences and his own. He talked about how a government agency had once provided him with a walking stick for the visually impaired, but that it had been poorly designed and frustrated more than assisted him.

Following this discussion, presented with a collage of group members’ statements, the participants were invited to draw links between the statements. A problem-tree was developed to explore the causes and effects of their issues. For example, lack of access to assistive devices was seen to undermine their self-confidence, which in turn led to a lack of confidence in applying for jobs. This, in turn, influenced other people’s lack of faith in their abilities. Participants were reluctant to apply for work or to start a business because they were convinced they would be rejected.

Mbah Muji holding a sign “I don’t have any problems!” Photo credit Irfan Kortschak

Once the relationships between all the individual stories became clearer, the next step was to create a story that expressed the relationship between these ideas. To enable the participants to create a dramatic story, the facilitators provided them with an example, the story of Si Nia, a blind woman who, despite her desire for independence and autonomy, was constrained by over-protective parents who objected to her relationship with a man called Anggoro, who was also visually impaired. By discussing the themes in this story, the participants were able to see how the themes that they had raised when drawing up the problem trees could be dramatized in their own theatre piece.

Because We Are Disabled

A major theme that emerged from the workshop was that many challenges the participants face stem from community beliefs that disabled people cannot work or be productive. However, everyone agreed that work and productive opportunities were exactly what the members of the group needed to address their exclusion from the community. The group collectively formulated a single short sentence that summarised their frustration: “Justru karena aku difabel, aku harus bekerja!”– ‘It’s because we are disabled that we need work!’ To express this idea dramatically, the group crafted the story of the young man raising chickens, whose inability to expand his business had nothing to do with the fact that he was blind, and everything to do with the fact that the financial institution field officers assumed that he would not be successful because he was blind.

Interestingly, when I asked the participants if any of them had ever applied for credit themselves and had their applications rejected, they all shook their heads with a ‘no’. They all described struggling to establish their own businesses with the limited resources that were available to them, sometimes using soft loans or small gifts of money or other resources provided by family members or members of the community, sometimes just building on the fruits of their own labor. Not a single one had ever applied for a loan from a formal institution. Dian, the bubbly and extroverted village activist, who certainly did not seem to lack self-confidence, said, “I think most difabled people just think there is no point applying, so we work out other ways of doing things.” The story the group presented was not so much about what had happened to anyone in the group, but what they feared or believed would happen.

So I asked Dian if she thought that maybe she or other members of the group might be more confident about applying for a loan after taking part in the workshop and the performance if it had given them the courage they needed to face their fears. She smiled and shook her head doubtfully: “It’s not just about our attitudes. Our attitudes can only change if other people’s attitudes change too.” I asked if she thought performing the group’s play could help change the attitudes of the broader community. And now she laughed outright at the naivety of my question. “I hope so. But it’s just a small step. It’s part of an ongoing process. It won’t change anything unless we keep on pushing to make things change.”

This article was originally published in Inside Indonesia on November 27, 2018, and has published with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Irfan Kortschak.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.