Twenty years after his death, the Nigerian dramatist Ola Rotimi is attracting renewed interest. San Diego State University hosted a webinar in April 2021 where the affection and reverence for the playwright were clear. Another webinar was held in his honour in August 2020 at Bowen University in Nigeria.

The appeal of Rotimi’s theatrical practice and vision is that they are based on his infectious humanism, conviviality and reciprocity. The playwright, director and scholar was born in Sapele, Nigeria in 1938, and passed away in 2000. He made a tremendous impact on Nigerian theatre as a director in a time when theatre played a significant role in shaping political thought around colonialism, the Nigerian Civil War and postcolonial society. In short, he was a decolonial artist (before the term came into vogue) who fostered humanism.

Rotimi’s theatre collective, Ori Olokun, which he established in Ile Ife in southwestern Nigeria in 1968, was a breeding ground for some of the most talented, resourceful and successful theatre artists to have emerged in Nigeria. The bonds they forged with each other also grew stronger as they aged. They developed a powerful camaraderie which was evident in the San Diego State University webinar.

The plays

His plays – known throughout Africa – include Our Husband Has Gone Mad Again, Kurunmi, Ovonramven Nobaisi and The Gods Are Not To Blame, which adapts the plot of Sophocles’s Oedipus Rex for Nigeria’s cultural context.

They focus on moral dilemmas: good versus evil and right versus wrong. Rotimi’s plays are easy to stage. They do not require elaborate or expensive sets and props. They also do not require theatre virtuosos or unfamiliar metaphysical constructs or conceits. And so they were accessible to African audiences, who were invariably moved by the productions.

Theatre for the people

Rotimi was also an innovator in his approach to what theatre can achieve and the tools it can use. He drew from indigenous traditions of drama, song, dance and mime. Though trained in Western theatrical tradition, he sought to break away from it and connect with homegrown theatre practices.

Local costumes, geographical settings, song and dance are prominently featured in all his major productions. He also innovated by challenging cultural boundaries: between professional performer and amateur; actor and singer; male and female; old and young; ivory tower and town.

Rotimi promoted a populist theatre, a theatre of conviviality that represented everyone within the community. This is evident in all his plays. Inclusion and community were ideas that informed his plays and practice.

And this has had a lasting impact. His concepts continue to inspire the people he trained in the Ori Olokun collective.

Theatre and community

Rotimi viewed theatre as a way of building community both inside the theatre world and beyond. He saw theatre not as a closed and artificial art form, but as a way of connecting past, present and future. In this view, theatre serves as a link to the wider community and ultimately our common humanity.

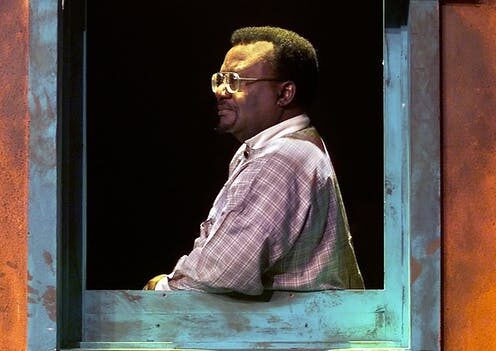

A scene from outdoor pidgin version of Grip Am, Ola Rotimi’s play, staged in Lagos in 2013. PC: Pius Utomi Ekpei/AFP via Getty Images.

After the play has ended, after the curtains have fallen and the lights are out, the community beyond continues. And all – performers, singers, actors and dancers included – have to return to it. But they do not return to it empty handed. They are supported by morals, ethics and a sense of social purpose and cohesion acquired during the play. It is the duty of each member of a cast to uphold and spread these ideals.

Thus Ori Olokun instilled within its members the belief that theatre is a community-building exercise, a project for engendering a sense of worthiness and belonging in every member of a production, including directors, performers, set designers, costumiers, lightning technicians and so on.

This conception of theatre is a contrast to the view offered by playwrights who explored alienation in the modern world – the likes of Ireland’s Samuel Beckett, France’s Eugene Ionesco and Jean Genet, and Britain’s Harold Pinter and Joe Orton. They wrote about despair, solitude, sterility, grim fate.

Rotimi’s theatre and teaching presented a vista of humanity. Though slightly idyllic, it was also practical and often realisable. For Rotimi, theatre is community, and ultimately, community is everything.

Rotimi’s humanism – like the southern African concept of ubuntu or the Tanzanian ujamaa – sees the collective rather than the individual as the predominant vehicle of social transformation. And if Rotimi continues to exert an influence more than 20 years after his passing, it is simply because his sense of humanism was both genuine and relevant.

This article was originally published on The Conversation on July 18, 2021, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Sanya Osha.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.