The play White Rabbit Red Rabbit is an experimental piece by the Iranian playwright Nassim Soleimanpour that has become a theatrical phenomenon. It has been performed around the world over 2,000 times in twenty-five languages since 2011, by a long list of acclaimed actors including Whoopi Goldberg, Alan Cumming, Stephen Fry, Nathan Lane, and F. Murray Abraham. The play has no director and no setting. Each night a different actor reads the script that they have never seen before, in front of a live audience.

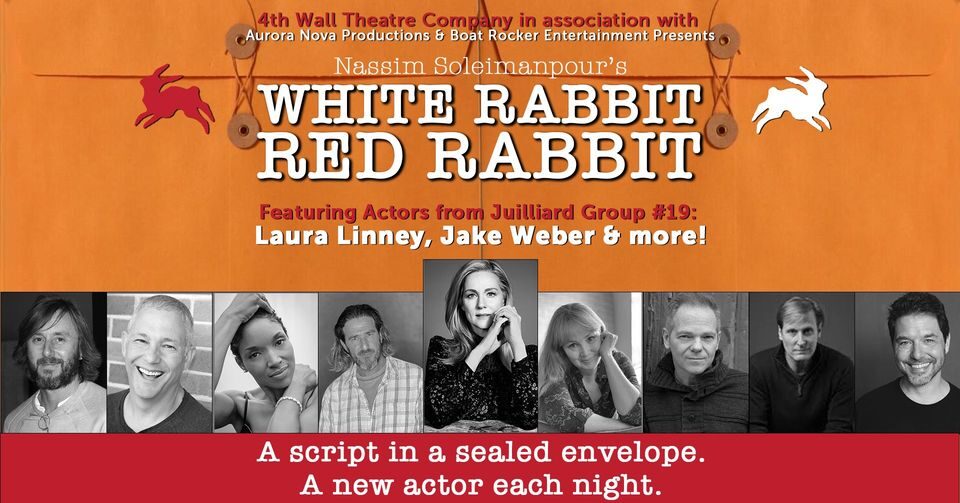

The play continues to be performed online during COVID-19 with the same approach, however, it features another level of experimental theater in that it is staged more intimately on Zoom, with performers in their own houses instead of the stage. This makes a more informal and friendly gathering for the audience. The performance creates an environment in which everyone feels at home and can warm up easily to the cold reading of the play. The White Rabbit Red Rabbit live Zoom show was organized by the 4th Wall Theater Company in Houston, U.S., from April 22 to May 2, 2021. It features different actors every night, including Emmy Award-winner and Tony and Academy Award-nominee Laura Linney, and the film and television star Jake Weber. I watched the play performed by Jake Weber on May 2. The audience are instructed to turn on their videos, mute their microphones and wave their hands in the air for applause. Some audience volunteers are unmuted by the organizers of the show so they can participate in the performance and play a character, and others could express their opinion in the chat. To form a collaborative show and at one point Soleimanpour’s email address is provided so he can receive the audience’s opinions.

The play starts with a light, playful mood but comedy gradually leans toward deeper and darker subjects conveying universal themes of authority and oppression, uncertainty, social conscience, isolation, suicide, and death. Soleimanpour uses animalistic imagery such as the rabbit, ostrich, crow, bear, and cheetah as symbols of real figures in society that is compared to a circus.

White Rabbit Red Rabbit play script is delivered to the performer in a sealed envelope.

The script is delivered to the actor in a sealed envelope, then starts with the playwright Nassim Soleimanpour introducing himself. He explains that he cannot leave Iran because he has no passport due to his refusal to fulfill military service as a conscientious objector. His play is the only way to communicate with the world and allows him to give instructions to audience and the actor from his apartment in Tehran. Through these instructions, the playwright orders the actor to pour a supposed, small vial of poison that was delivered to his house into one of the two glasses of water next to them. The actor’s assistant then follows instructions to change the places of glasses from right to left while the audience are asked to close their eyes.

The playwright is the sole authority who decides how to involve the audience and the performer, from making the actor imitate an ostrich to choosing volunteers from the audience to play rabbits, a bear, and someone who reads the final lines of the play. The play is an experiment for both the audience and performer, creating awkward and funny situations that catch the actor and audience off guard. The author and performer directly address the audience and break the fourth wall. The play’s narrative spans many locations and time periods, starting with the playwright describing his state and then connecting it to a story of a rabbit going to a circus. There, the rabbit is told by a bear to hide her ears. The playwright then skips to his own life in which he dreams of traveling to famous cities in other countries while uncertain of his fate in Iran for the unforeseeable future. Meanwhile, the imagery that he creates is a familiar feeling to the audience, who indicate interest with their applause and participation in the performance. Everyone can identify with isolation and uncertainty due to COVID-19.

Social conditioning is another concept symbolically represented in the play through five audience members volunteering to act as a red rabbit and white rabbits put in a cage by the playwright’s uncle (a symbol of authority). The rabbits strive to reach a carrot at the top of a ladder; the red rabbit races for the carrot every time while the white rabbits get dunked with ice-cold water instead. White rabbits attack the red rabbit as they are annoyed by getting wet, but the red rabbit continues to go for the carrot. Over time both the water and the carrot are removed from the cage and new rabbits replace the old ones, but despite the changes, the rabbits continue the same behavior. The red rabbit goes for the imaginary carrot and the white rabbits attack him. The story indicates that society is conditioned to confront those who display individuality.

The playwright’s narration slowly turns up the heat by asking for more daring acts from the performer. Weber has performed enthusiastically from the start of the show, and engaged the audience with his intuitive reactions throughout the play. He used comedic tones for the ostrich and a rabbit looking for a cloth to hide his ears, and a darker tone of suspense with the issue of suicide. He simultaneously poured the water from both glasses over his head as everyone anticipated whether he would drink the poisoned water or follow the audience’s instruction not to. Soleimanpour puts everyone on the spot and uses suspense by making the audience decide the fate of the show. They have been conditioned to follow the playwright’s orders from the start, but will they encourage the actor to drink the poisonous water as per the writer’s instructions, or will the audience object? In the virtual space, they can do this by writing their thoughts in the Zoom chat, leave the meeting or passively observing an act of violence. Perhaps the audience feels less able to express their reactions as loud as they would in a theater. Though they are muted in Zoom, they see each other’s faces and reactions more clearly with everyone being in their fully lit rooms. This creates a sense of unity among the audience.

White Rabbit Red Rabbit has appealed to the whole world. Soleimanpour, who no longer lives in Iran, has written seven more plays and has become one of the most celebrated contemporary Iranian playwrights. To my surprise, many drama students and theater academics in his home country are unaware of his works. This could possibly be due to theater elites in Iran intentionally choosing to neglect his work or because the content of his plays does not follow guidelines set by the Centre for Dramatic Arts, a subdivision of the Ministry for Culture and Islamic Guidance.

As a theater graduate from Tehran, I was excited to see a play by an Iranian playwright that has been well received around the world and yet surprised that I had not seen his work performed in theaters in Tehran. I was lucky to watch the play given the challenge of purchasing the ticket and the difficulties of connecting to Zoom, which was blocked in Iran until recently. International credit cards do not provide services to Iran due to US sanctions, which subsequently caused the devaluation of Iranian currency. This makes a ticket to a foreign play equal to almost one-third of the average salary in Iran. A friend who lives in the US bought me the ticket and I was lucky to connect to the video communication platform easily since it is now allowed in Iran. This could be that recently a softer approach has taken towards some social media. Given these circumstances, I could clearly relate to the play’s narrative about the ordeal of connecting to the outside world.

While his experimental play can easily interact with global audiences on stage with the audience seated in the dark theater, or in a virtual space with a more relaxed environment at home, other contemporary Iranian plays that are considered part of the canon of aestheticism and dramatic literature have failed to reach the world. They remain less well-known than Soleimanpour’s rabbits who hop onto the international stage to deliver universal images and paint a picture of people of Iran that differs from that displayed by Western media. Meanwhile, the play strikes a chord with Iranians who can deeply identify themselves as the rabbits covering their ears at the circus, facing cheetahs pretending to be ostriches.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Niloofar Mohtadi.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.