Thanks to the early 20th century ethnographic research of Milman Parry and Albert Lord, the word ‘guslar’ may be more familiar – if at all in the English-speaking world – as a term indicating a musical storyteller in the Balkan tradition, frequently accompanied by a one-stringed musical instrument ‘gusle’.

Lubuski Teatr from Poland, in their production Gusła, directed by Song of the Goat’s Grzegorz Bral, draw on the more complex Polish etymology of the word “gusła”, denoting beliefs in supernatural events. The term gusła connects to “guślarz,” meaning shaman, and Lubuski also offer Witchcraft as a potential translation for this show’s title. This trans-Slavic coincidence may be another proof, if one was needed, that links between narrative performance and shamanism are fundamental to the history of theatre.

Bral’s production, showing at Summerhall during the Edinburgh Fringe this August, takes excerpts from the classic of the Polish Romanticism Dziady (Forefathers’ Eve) by Adam Mickiewicz. Revolving around a pagan ritual performed on All Souls Day which brings into contact the dead and the living, this shadowy work privileges emotional content over dramatic action – or at least this is how it comes across without any translation of the dialogue.

Over the last 20-odd years Bral has honed a performance style and shaped audience expectations with his own company Song of the Goat which specialises in training new generations of actors in ritual, song and movement-based theatre. By comparison, the Lubuski ensemble are more diverse in age and training background, and they have the intensity and sturdiness of seasoned character actors to whom the language of ritual and the elaborate costumes and headdresses (modelled on Siberian ritual attire) offer scope for a more epic dimension than the usual dramatic repertoire allows. The 9-strong ensemble talk mostly directly to the audience, fixing us with their stares and enveloping us in their carefully cast spells. However, it is mostly the accompanying trickling piano (Maciej Rychly, Daniel Grupa & Kosma Mueller) that ensures we keep our attention fixed on the proceedings.

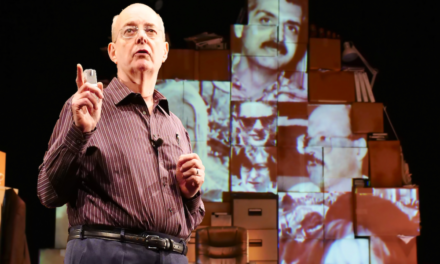

Andronicus Synecdoche. Song of the Goat. Photo by Mateusz Bral.

At the same time, Song of the Goat’s production of Andronicus Synecdoche at Zoo Southside offers insight into a very different – and more typical – example of Bral’s work. Here an adaptation of Shakespeare’s play is presented at a gratifyingly accelerated pace by eleven actors who play out short scenes framed by Bral’s own dynamic narration from a music stand. It is all delivered in English and underlined for some reason by English subtitles. The director appears to have replaced the aspects of the plot that were of a lesser interest to him with contextual storytelling to lay the stage for those interactions whose performative renderings he chose to explore with the ensemble. The result is reminiscent of a masterclass/performance Edinburgh audiences have seen from Song of the Goat before (for example in Songs of Lear 2014). However, the form has evolved into a seemingly new genre which also weaves some unexpected opera singing together with the folk polyphonies more commonly associated with this company’s work.

The visual presentation is thus pared down to a set of monochromes. Occasionally the director steps aside to join the three-piece orchestra, and in a couple of isolated moments also engages in episodes of acting and dancing with the ensemble members. This too is certainly a more stylised development of his previously established role of an announcer introducing and presenting his company’s work in progress to the audience. Making virtue out of necessity, Bral’s own work can therefore be seen as potentially aspiring towards the part of a guślarz-guslar-shaman in itself.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Duška Radosavljević.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.