“Patriarchy is a judge that judges us for being born” proclaims the banner wrapped above our heads, twined about the black box Mark O’Donnell Theater. It is a saying often associated, in one wording or another, with Chilean activists under the Pinochet dictatorship. “Patriarchy is a judge,” proclaims the banner. And Smith Street Stage’s innovative reimagining of Shakespeare’s most infamous problem play proceeds to prove it.

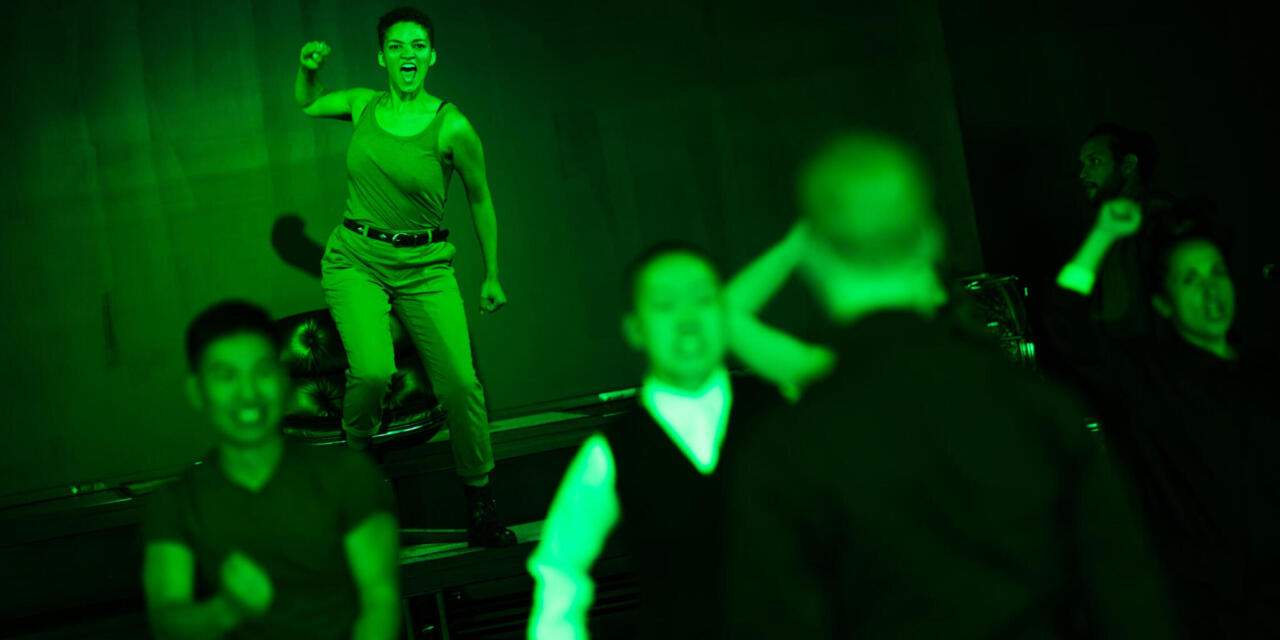

This Measure for Measure opens with a musicalized chant, growing in intensity. The women of our show—we will grow to know them as Mariana, Juliet, Pompey, Overdone, and Isabella—gather in revolt against the President’s policies. Their cries, in Spanish, against “El Presidente!” crescendo in a controlled frenzy; Mariana, as a militant feminist, faces off against Angelo center stage. At female break, their fists in the air, our story begins. It is a marvelous way to establish tone and grab one’s audience: this contemporizing of Measure for Measure (directed by Beth Ann Hopkins and Raquel Chavez) is unapologetically political, brutally honest in its parallels, and focused entirely on gifting their women a voice.

Smith Street accomplishes this without changing a word of Shakespeare’s original work. The Duke still places entitled Angelo in charge, claiming to travel when truly he is disguising himself as observant Friar. Claudio is still arrested for impregnating Juliet before marriage. His novitiate sister, Isabella, is still called upon to plead with Angelo for his life, and subsequently told that she must have sex with him to save her brother. Claudio still pleads with Isabella to do so; Angelo still attempts to assault her. The Duke never steps in to save these people, preferring to play with lives and souls. And the resolution is still horribly unsatisfying in Angelo’s punishment (marrying his wife whom he left years ago), Isabella’s “prize” (the Duke’s proposal), and the lack of apology for all. Except, this time, it is less unsatisfactory: the Duke does not receive the final word. The women do.

Mahayla Laurence (L) and Aileen JiaLing Wu as Mariana and Isabella. PC: Bjorn Bolinder

There is a particular genius in Smith Street’s parallelism. The issues of Elizabethan Vienna don’t seem very far from contemporary strife in this production, not when the vilified whorehouses become abortion providers running for their lives, or when Claudio is dragged from his growing family by power-hungry, single-minded police officers. The feminization of governmental Escalus (a pointed Toni Kwadzogah) and clown Pompey (an iconic Daniella Rabbani) provide query into both internalized misogyny and the entrapment of patriarchy: the former struggles to help her fellow women for fear of losing high-ranking position, though she attempts to play the system; the latter finds herself within a balancing act, hiding her involvement in abortion rights and assisting in the prison-industrial complex (as executioner) when her life depends on it. The structural marriage of police brutality with the assault on reproductive rights, a marriage that finds itself in most contemporary societies, and establishing it under an Angeleno dictatorship, gives us an undeniable sense of timeliness. A centuries-old play feels refreshed; one is left questioning in the best of ways.

Here, I believe, is where kudos are called for. This exceptional crew of actors took a much-needed adaption and ran with it. I don’t believe it would have worked without their capabilities, in fact. Tobias Wong and Delia Kemph provide impeccable dichotomy in their dual portrayals: as Claudio and Juliet, the two held marked, gentle chemistry; as Elbow the Idiotic Cop and Abhorsen the Unfeeling Executioner, they provided wonderfully dark humor. Together, they are the forced duality of their world, and, thus, of ours. Keith Hale, as the Duke, succeeded in instilling whimsy and hilarity in, arguably, the morally worst character of the play. I, indeed, laughed as I grew to despise him. On a similar note, Jonathan Michael Hopkins gave a masterful performance as Angelo. He is a horrific character, a villain through and through with no textually redeeming qualities, yet Hopkins managed to provide him with some depth: in Angelo, we see cyclical patriarchy and toxic masculinity, a product of his surroundings. Isabella, portrayed by Aileen JiaLing Wong, was his perfect opposite: her “To whom should I complain?” monologue was perfection, bringing my heart to my throat. She had a voice, and she was allowed to use it. And I would be remiss if I didn’t provide praise to Christian Negron, our quiet Provost: though he spoke the least in the play proper, his physicality, his actions, his endowment provided a conflicted depth to a servant of the dictatorial empire. I found myself compelled to watch him with constancy, and I do believe his performance and the query behind it embody this production.

Delia Kemph as Juliet. PC: Bjorn Bolinder

The set design, by Lucas A. Degirolamo, was wonderfully effective, simple, and punchy. The lighting—in which one can see the police state dichotomy in shades of blue and red, and stark reality in blaring white—was cleverly done by Xiangfu Xiao. The sound design and music, primarily provided by Mahayla Laurence (Mariana), added a sense of grounding, of reality, to the most devastating of scenes. I must give massive applause, as well, to the use of an intimacy coach (Leyla Beydoun): thank you for continuing the movement, Smith Street.

That all said, there were slight consistency issues: I was confused as to why Mariana was portrayed as a militant feminist fighter, but so easily submitted to her sex offender husband; I also could not find the throughline of the feminist movement illustrated in chants at the opening and finale; I was unsure of some of the more choreographic elements. Still, I do believe Smith Street Stage has succeeded in this reimagining. They so deserve their audiences, and I am grateful that their production exists.

Toni Kwadzogah as Overdone. PC: Bjorn Bolinder

For more information, and to purchase tickets, visit Smith Street Stage.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Rhiannon Ling.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.