Teatro Biondo Stabile in Palermo has a full-house. To the right, left and up in the surrounding galleries are a mixture of different generations: ones who were there thirty years ago and ones who were absent — even unborn — at that time but grew up with the narrative of this past event. In front of the sitting and anxious audience, a wide vertical screen covers the stage that depicts a demolished wall and the front few rows of a theatre (perhaps Teatro Biondo). This live and mediated audience will be soon joined by a unique experience of remembering and witnessing.

Thirty years ago under the warm support of Leoluca Orlando during his first term as the Mayor of Palermo, Teatro Biondo offered — using the terminology of today — a residency opportunity to Pina Bausch and her company. Back then, the theatrical stage of Teatro Biondo became a place for choreographic research and experimentation that culminated in the production of Palermo Palermo (1989), a piece that left a strong imprint on the local dance scene and since then has travelled around the world making the name of the Italian city familiar all over Europe as well as in New York, Taipei and Kawasaki City. Less of a depiction or an analysis of the cultural landscape of the city — but with a few clear references to Palermo — and more of an opportunity for the choreographer to delve deeper into the human relationships that are found at the core of her artistic signature, Palermo Palermo. A Piece by Pina Bausch is the mediated version of Palermo Palermo that has just been transferred to the screen by the editions of the Pina Bausch Foundation. The 3rd of November was its online free release contemporaneously to an evening in Teatro Biondo celebrating the memory of Pina Bausch, who passed away exactly 10 years ago and marking 30 years since the creation of the work Palermo Palermo.

This event also consisted of a photo exhibition under the title Macerie e tacchi a spillo. E cadde un muro…Palermo 1989-2019 (Rubble and High Heels. And the Wall Falls…Palermo Palermo 1989-2019) by Piero Tauro, whose photos from the historic event in Palermo, as well as the recent version of Palermo Palermo (2019) performed by Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch, will be accessible to the public until the 1st of December of the current year. Quello che ci muove. Gli spettatori del Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch ricordano (What moves us. The Spectators of Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch remember) under the direction of the visual anthropologist Rossella Schillaci from the idea of the Italian dance scholar Susanne Franco, is a short film presented during the same evening.

More specifically, Quello che ci muove presents a series of audio-visual fragments from the most well-known choreographic works of Bausch voiced over by the narrations of selected audience members that had the chance to attend her work. Based on one of the most quoted phrases by Bausch “I‘m not interested in how people move, but what moves them” (Bausch cited in N. Servos 1978,1984) and inspired by the book Quello che ci muove. Una Storia di Pina Bausch (B. Masini, 2017), the film Quello che ci muove attempts to bring insight into what moves — emotionally — Bausch’ s audience. The tone of their voices and their personal confessions collected after a public call for memory contributions conveys their feelings and their emotions, what emerges during and what remains after the end of a performance. Dance, transient and ephemeral by its nature, disappears as it happens and Quello che ci muove explores what survives and persists after the completion of a Bausch evening.

In the scholarly discourse on archiving and reenacting dance (the most recent term for referring to the reconstruction of choreographic work that critically and philosophically questions past, memory, and heritage in relation to the present), employing oral history as a method is a rare approach. A remaking process is often examined through any available audio-visual and notational resources and most importantly through the body of the performer as an archive — as a carrier of embodied knowledge who needs to pass it on from one generation to the other. But in Quello che ci muove audience becomes one of the main sources in the process of re-membering (putting together) the gaps of past choreographic events created by Bausch; their individual experiences re-inform our knowledge of the past.

Macerie e tacchi a spillo. E cadde un muro…Palermo 1989-2019 and Quello che ci muove. Gli spettatori del Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch ricordano prepare the spectator to cross the doors of the main auditorium of Teatro Biondo where both Bausch and her dancers stepped 30 years ago during the choreographic residency for the creation of Palermo Palermo. Tauro’s photos and the archival footage of Quello che ci muove assist the audience in embracing the mediated version of Palermo Palermo that will soon unfold on stage. They help the audience, especially the ones who attended the original event in its three-dimensional glory, to adapt to the flatness and two-dimensionality of the screen.

Palermo Palermo. Ein Stück von Pina Bausch (Palermo Palermo. A Piece by Pina Bausch ) is a film composed of multiple versions (documentations) of the choreographic work, Palermo Palermo, that was originally co-produced back in 1989 by Teatro Biondo Stabile of Palermo and Andres Neumann International. Some of the most common characteristics of Bausch’s work are already crystallized and recognizable in Palermo Palermo; strong imagery that invites the audience to contemporaneously think and feel, image juxtaposition, movement vocabulary based on gestures, repetition, the transformation of beauty and the gradual change and use of the theatrical set during performance. Besides a few direct connections with the city of Palermo, such as the street filth and the precarity of water sources, the overall choreographic rhythm of Palermo Palermo — applicable to many other occasions of Bausch’s choreographic oeuvre — reflects the succession of acceleration and slow gaps of time that are characteristic of life in Palermo (as claimed by Francesco Giambrone, dance critic and the current superintendent of Teatro Massimo, Sulle tracce di Pina Bausch, F. Quadri, 2003).

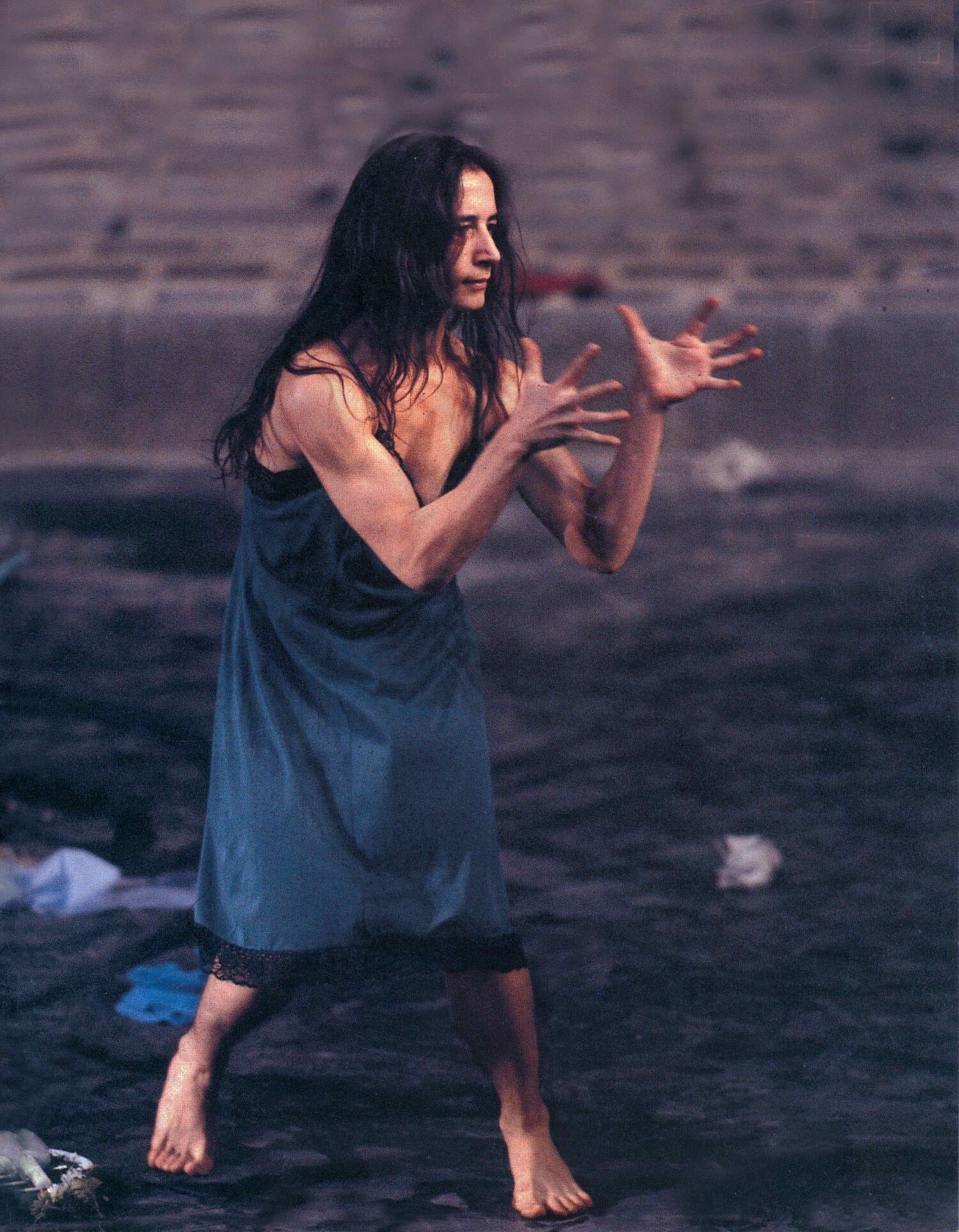

Shanahan in the opening scene of Palermo Palermo. Photo credit Piero Tauro.

The brick wall that appears when the curtains open is anonymous and its fall may be a metaphor for the destruction of borders that, in the case of Palermo, signaled the end of a period of isolation and the beginning of a cultural blooming. The falling wall could also refer to the rupture with the past — also known as the sack of Palermo — that happened from the 50s until approximately the mid-80s through the demolition of some of the most precious architectural treasures of Palermo that were replaced by modern blocks of apartments. However, it is not a coincidence that the premiere of Palermo Palermo took place in Wuppertal on the 19th of December 1989, approximately one month after the fall of the Berlin Wall. As a result, Bausch’s work is always open to interpretations according to the viewer’s personal experiences.

The screen version of Palermo Palermo is the outcome of a carefully crafted editing of more than 10 different performance video recordings — eight from 1990 and one from each of the following years: 1989, 1992, 1995, 2011. The editing is a true masterpiece considering all these versions are combined together. Since the screen version makes use of material that spans over 10 years, some of its characteristics include the subtle changing of the physical appearance of the performers through time as they get older, as well as the different registrations of film qualities according to the developments of technology (for instance the sometimes grainy image versus the crystal high-definition).

Furthermore, one of the most common issues in the process of documenting a live-work is the camera frame and more specifically the use of wide view versus the close-up. While the latter gives the chance to delve into details sometimes lost in the overall image, the wide frame provides an overview of the multileveled scenes that unfold contemporaneously on the stage and allows the viewer to choose where to focus attention. While the close-up may engage the audience and create an increased emotional impact, the wide frame may distance the audience from the emotion which is so crucial in Bausch’s work. The size of the camera frame raises an additional issue of great relevance, the time nuances and variations in relation to space as mastered by Bausch exclusively for the live performance versus the theatrical time of the live performance as depicted on the screen. Time runs in a different manner on stage and screen. Despite these issues, which are handled with care, the archival audio-visual document succeeds in displacing us thirty years earlier. In a synchronicity of different temporalities, the live and mediated audience are joined in amplified applause that manifests our approval of this unprecedented project.

The three-part event was an announcement of the future project palermoWpalermo (where W stands for Wuppertal) which anticipates putting Palermo Palermo back on the stage of Teatro Biondo during the season 2020-2021 with a mixed cast consisting of professional performers residing in Palermo and members of Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch. The philosophy of Pamela Villoresi, the current director of Teatro Biondo, is to create future opportunities for the artists of the city by looking back to the past and the most important events in the history of the local theatre. However, a question to keep in mind and it is always crucial in the revival of any historic work is: should the work be preserved as it was or should it take into consideration the context of today? In the case of Palermo Palermo and any of Bausch’s works, answering this question becomes more difficult considering the fact that the dancers — citizens of 1989 when referring to Palermo Palermo — have produced the material of the work and became the co-authors in the choreographic process. This way of extracting material from the dancers imposes a further difficulty in the remaking process which is not only concerned about the movement restoration of “steps,” dynamics and phrasing but on building and re-awaking emotions in the new cast of performers and by extension on the audience. Without the careful eye of Bausch to supervise this process, the difficulty will be harder and the responsibility even greater.

Beatrice Libonati in Palermo Palermo. Photo credit Piero Tauro.

Answering the question regarding the necessity of Palermo Palermo to correspond to the present moment or not will be the difficult task of Jan Minarik and Beatrice Libonati, historic members of the Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch and members of the original cast of Palermo Palermo who, under the supervision of the Pina Bausch Foundation, will direct the choreographic process and production of palermoWpalermo at Teatro Biondo. They will decide whether to combine the different temporalities of then and now in order to respect the overall frame of the piece and enrich it with the personal contributions of the performers-citizens of Palermo and Wuppertal or preserve it strictly in its initial form. Keeping in mind this frame, we need to release ourselves from any pre-defined expectations and open our eyes and our hearts to the new that will unfold from this process.

General Info:

Palermo Palermo (2019) by the Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch will tour in several locations in the USA (Los Angeles, Berkeley, Chicago) during spring 2020.

Palermo Palermo. A Piece by Pina Bausch is now available online on the page of the Pina Bausch Foundation.

Quello che ci muove. Gli spettatori del Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch ricordano is stored as a single copy in the digital archive of the Pina Bausch Foundation.

The photo exhibition under the title Macerie e tacchi a spillo. E cadde un muro…Palermo 1989-2019 will remain open until the 1st of December 2019 in Sala Guicciardini of Teatro Biondo in Palermo.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ariadne Mikou.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.