The Egyptian Tanoura Folkloric Dance

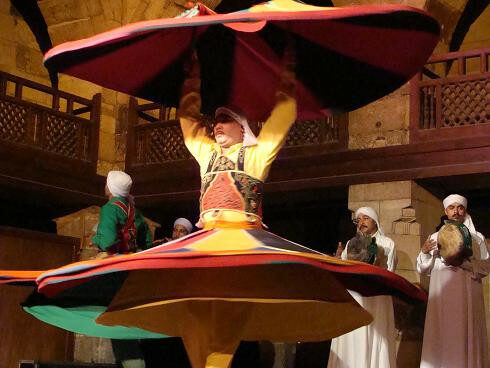

The Tanoura dance or spectacle is a mystic, Sufi, folkloric Egyptian type of dancing. It is performed three times a week throughout the year. The show takes place in an equally mystical and historical ancient place in old town Cairo called Wikalat Al Ghory, “the Ghory Foundation,” a 16th-century marketplace built by the Sultan Qunsuwah Al Ghouri, and since the 18th century used for artistic and social purposes. Hence, the authentically profound and rich setting reflects and emphasizes the overall purpose and meaning of the Sufi spectacle. Although the performance is intended to be a hymn praising the beauty of God and seeking his blessing and forgiveness, it most certainly transcends any conventional boundaries of time, place, space, culture, or even religious affiliation. The show begins with a group of singers reciting old verses partially Koranic, partially ancient poetry, setting the mood for a leap into the sublimity and nostalgia of a well-known and much-favored art in Egyptian history called “Al Tawasheeh,” or the reciting of old verses. Smoothly, without any sudden or abrupt movements, the singers begin to move slowly and gradually in steady individual circles, each in his own space. They simultaneously play their own tunes, each using a different instrument. The instruments are primarily different types of Egyptian drums or “Tabla.” However, there is also a pharaonic lute, percussion, and Sagat (used by ballad dancers). Surprisingly, the seemingly paradoxical tunes build up to a single unified, harmonious melody, thus encapsulating the main theme of the show, which is the undivided and powerful beauty and power of the one and only God. During the final part of the show, which lasts nearly two hours, six older skirts or Tanoura dancers occupy the stage. The lights are dimmed, and a single utterance is repeated over and over, namely “Allah,” the Creator and also the Beauty. The dancers move vehemently, almost feverishly on the stage in continuous, persistent circles, holding up their skirts for 45 minutes! They are occasionally interrupted by the passionate and rigorous applause of the bewitched audience. Although typically Egyptian and religious in its essence, the performance is internationally global in its mesmerizing, soothing, cathartic effect for the audience, whether they are Egyptians, foreigners, or even children, which is the usual mix of viewers due to the historical significance of the place. The director, sound technician, and lighting engineer of the show remain anonymous.

The Tanoura dance or spectacle is a mystic, Sufi, folkloric Egyptian type of dancing. It is performed three times a week throughout the year. The show takes place in an equally mystical and historical ancient place in old town Cairo called Wikalat Al Ghory, “the Ghory Foundation,” a 16th-century marketplace built by the Sultan Qunsuwah Al Ghouri, and since the 18th century used for artistic and social purposes. Hence, the authentically profound and rich setting reflects and emphasizes the overall purpose and meaning of the Sufi spectacle. Although the performance is intended to be a hymn praising the beauty of God and seeking his blessing and forgiveness, it most certainly transcends any conventional boundaries of time, place, space, culture, or even religious affiliation. The show begins with a group of singers reciting old verses partially Koranic, partially ancient poetry, setting the mood for a leap into the sublimity and nostalgia of a well-known and much-favored art in Egyptian history called “Al Tawasheeh,” or the reciting of old verses. Smoothly, without any sudden or abrupt movements, the singers begin to move slowly and gradually in steady individual circles, each in his own space. They simultaneously play their own tunes, each using a different instrument. The instruments are primarily different types of Egyptian drums or “Tabla.” However, there is also a pharaonic lute, percussion, and Sagat (used by ballad dancers). Surprisingly, the seemingly paradoxical tunes build up to a single unified, harmonious melody, thus encapsulating the main theme of the show, which is the undivided and powerful beauty and power of the one and only God. During the final part of the show, which lasts nearly two hours, six older skirts or Tanoura dancers occupy the stage. The lights are dimmed, and a single utterance is repeated over and over, namely “Allah,” the Creator and also the Beauty. The dancers move vehemently, almost feverishly on the stage in continuous, persistent circles, holding up their skirts for 45 minutes! They are occasionally interrupted by the passionate and rigorous applause of the bewitched audience. Although typically Egyptian and religious in its essence, the performance is internationally global in its mesmerizing, soothing, cathartic effect for the audience, whether they are Egyptians, foreigners, or even children, which is the usual mix of viewers due to the historical significance of the place. The director, sound technician, and lighting engineer of the show remain anonymous.

On the Threshold (Khatii el Attaba), written and narrated by Sahar El Mougy

On the Threshold is a modern one-act play, written and narrated by Sahar el Mougy, Afaf el Said, Omar Sameh, Essam Faiz, Carol el Akkad, Rania Zahra, Rasha Nashaat, and Summer Ali; with lighting designed by Sherif el Boreii and sound by Shadi Mahmoud. The production was directed by Sahar El Mougy. The play attempts to investigate the reasons behind the existential entrapment of six women and two men after being stranded on an island due to a shipwreck. The spectacle, which lasts about two hours, is organized within a series of cultural and theatrical performances by an NGO cultural foundation called “dome” which is symbolic of an Egyptian kind of fruit-herb. The play takes place in the old Coptic district of Ramses in the city of Cairo. The theatre was donated by an old Coptic (Christian) school. The show is primarily a narrative one in which the eight characters narrate their reasons for joining this particular cruise. The storytellers have very different social and intellectual backgrounds. After finding themselves stranded on the deserted island, they are forced to share their life experiences and stories because there seems to be nothing else to be done. Their voices intertwine, via their separate monologs, as they form an intricate maze of tales. It is an imaginary, fabricated world where different “voices” are forced to hear “others” which echo their own subconscious. The coquette poetess, Hasnaa Abd el Ghani, meets with the clumsy government employee, Mrs. Mahrous, who sympathizes with Loulou (the girl who never stops dancing). Parallel to these voices is the shrugged squeak of a shy working girl who deals with life only through her camera lens. On the other side of the “echo,” there is the down-to-earth male, seemingly the confident voice of Mahmoud (a taxi driver). Moreover, we get to know the story of the materialistic, self-centered business woman, Sohaila al Ghandour. Last but not least is the police officer, Essam el Fayoumy, who acts out male sovereignty and dominance, when in fact, all he dreams about is a woman’s embrace (we learn this from his story). Unfortunately, the lack of action and the length of each narrative creates a kind of monotony in the overall mood of the performance—a monotony broken, thankfully, by the hilarious humor and sarcasm of some of the narrated tales. The stage decor is almost nonexistent except for cushions scattered on the floor. The lighting is dim, to suit the melancholy of the narrated tales. Gradually, each character realizes that this “forced isolation” is, in fact, a “resolution” to their hollow, pathological existence/identities, which they have left behind (on the shore). Interestingly enough, the audience seems to assume the role of psychiatrist, healing the actors (patients) by merely witnessing and listening to their confessions. The play ends as inconclusively as it begins. The characters move in circles, coinciding with and occasionally bumping into one another. The message seems to be that no matter how intensely we exchange our stories, we still end up complete strangers. Hence, we are doomed to live on our separate, “isolated” islands, no matter how desperately we reach out for communication and empathy.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Nesma Youssef Idris.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.