For the past two years, Samoan playwright Victor Rodger has been tireless in bringing plays by non-white writers to New Zealand audiences through play readings staged in all of the main cities under the banner of his production company FCC (Flow, Create, Connect). FCC has presented readings of plays by Lorraine Hansberry, Robert O’Hara, Dominique Morisseau, Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, Amiri Baraka, Tarell Alvin McCraney, James Baldwin, Anna Deavere Smith, and R. Zamora Linmark as well as plays by Pacific writers such as Makerita Urale and Tusiata Avia. Few, if any, of these writers, would be familiar to regular theatergoers in New Zealand. Therefore, Rodger has been doing a necessary job of educating audiences and practitioners of the possibilities that lie in looking beyond white stages for quality drama. All of the readings have been very well received and now one of those plays The Mountaintop (2009) by Memphis-based Katori Hall has received a full production at Auckland’s Basement Theatre, directed by Fasitua Amosa.

Sensing something special, I flew up to Auckland for the night to see The Mountaintop and was rewarded by a performance that is a highlight of my theatre-going year. The capacity audience included various luminaries of Auckland theatre and the elder statesman of Pacific literature, Albert Wendt. The last time I’d been in the Basement Theatre was to see another FCC production, Victor Rodger’s Club Paradiso (2015). In that tight, relentless hostage drama, Rodger managed to scare me and the rest of the audience half to death as we witnessed a methamphetamine-crazed killer on a suicidal binge (Robbie Magasiva) tormenting his victims in a seedy South Auckland bar.

David Fane as Martin Luther King in The Mountaintop by Katori Hall, Basement Theatre Auckland 2017. Photo credit: Andi Crown

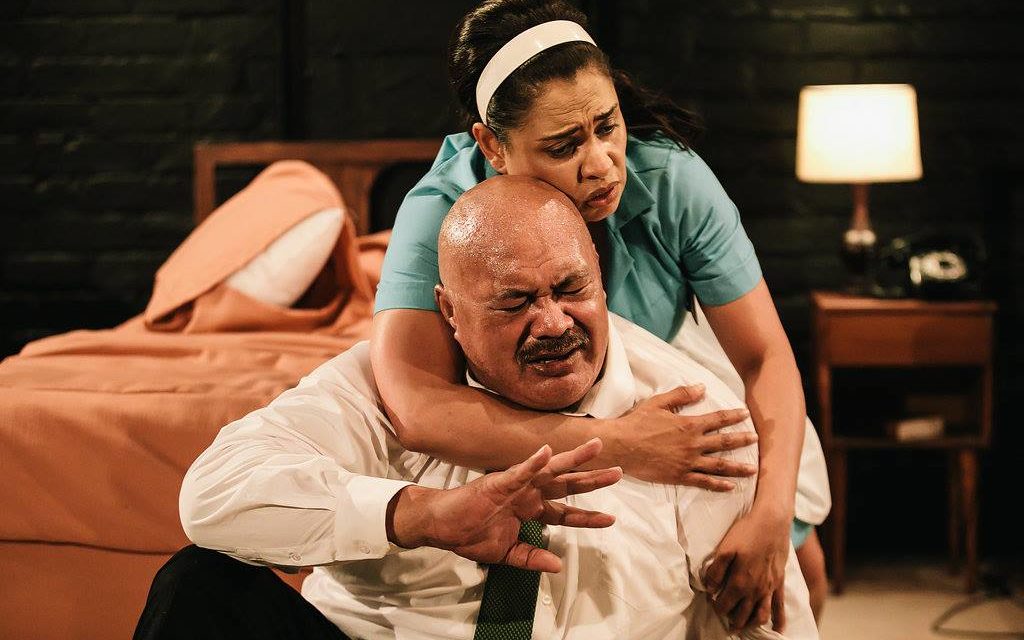

In Club Paradiso, the claustrophobic, low-ceilinged, black-bricked Basement was the perfect environment for the sweaty intensity of the work. The same setting was also ideal for The Mountaintop, which is set in the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee in April 1968 a few hours before the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King. The black brick wall perfectly integrated with the set design by Donna Marinkovich featuring two chunky wooden single beds with pink bedspreads and some neatly detailed retro decor. The audience crammed around the thrust stage on the Basement’s rustic benches, only arm’s length from the actors, close enough to experience every nuance of the performances. Under this intense scrutiny, David Fane as Martin Luther King and Nicole Whippy as the motel maid Camae gave heart-breakingly truthful performances. Fane is celebrated for his comic genius on stage and screen, but here he produced a dramatic performance of such variety and finesse that we were with him every moment. Whippy, who became famous for her sassy characters in TV series such as Outrageous Fortune and Nothing Trivial, recently returned to the stage for the first time in several years playing a variety of roles in the Silo Theatre’s A Streetcar Named Desire. She matched Fane perfectly, moment by moment and breath by breath. Their sense of complicity with each other and the audience was palpable, building to the standing ovation at the final fadeout. Faultless direction by Amosa served the play superbly, matching the beats of the script with perfect pacing and mood transitions, using every inch of the cramped space and creating striking imagery with simple means.

Katori Hall’s script, which won a Laurence Olivier Award in London in 2010, brilliantly weaves the facts of Martin Luther King’s life and death into a fictional encounter between King and Camae a few hours before King’s untimely death. Deafening thunderclaps provide an ominous sense of threat, as King’s fears and insecurities are revealed. Echoing Bert O. States’ definition of theatre as “great reckonings in little rooms,” Hall’s script opens out from its intensive encounter to the pages and stages of history, revealing the greater significance of King’s life and death. This is a story of struggle, justice, and inspiration, in which God becomes re-imagined as black and female. The script is as delightfully playful as it is deadly serious, incorporating everything from the pillow fight King had in the motel room with two colleagues shortly before his death, to his famous I’ve Been To The Mountaintop speech. Through revealing some of his flaws, Hall captures the humanity of a man who was seen as a god to many. Camae is written as a tour de force role, a maid who is not what she seems. At first, presented as a vivid portrait of a working-class African American woman, her mysterious insights into King’s psyche are eventually revealed as having a higher purpose. She challenges some of King’s methods and beliefs, bringing wider debates from the civil rights movement into the theatre. The script demands that audiences both acknowledge the larger histories of racial oppression and examine their own personal responsibility in advancing the cause of social equality.

Nicole Whippy as Camae in The Mountaintop by Katori Hall, Basement Theatre, Auckland 2017. Photo credit: Andi Crown

Katori Hall famously took a director to task in 2015 for casting a white actor in the role of King in a production of The Mountaintop at Kent State University but gave permission for Pacific actors to play these roles in this New Zealand production. Without making a big thing of it, having a Samoan and a Fijian actor in these roles subtly points up the script’s relevance to New Zealand, where racial tensions were fuelled in the 2017 parliamentary election as migration became a contentious political issue. If anything, the play seems even more relevant than it was in 2009, with Trump’s presidency signaling a malevolent racist backlash in the U.S.A. and elsewhere.

As New Zealand’s population becomes increasingly more multi-cultural, why do our major theatres continue to privilege white writers? In a piece he wrote for Playmarket’s 2017 publication The State Of Our Stage, Victor Rodger criticized New Zealand’s mainstream theatres for failing to program works by Pacific writers. Referring to the FCC playreadings, he writes, “in this new era of resistance, I’ve been resisting the status quo in my own small way…The plays I select are always by a non-white playwright, have normally been untouched by New Zealand producers and give #diverse practitioners a chance to engage with meaty, well-written, complex texts that they generally aren’t being given the opportunity to engage within the mainstream.” There is a startling synchronicity between the themes of Hall’s play and Rodger’s vision of a theatre that de-centers the privileged white gaze. With FCC’s full production of The Mountaintop, he magnificently proves his point.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by David O'Donnell.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.