In December 2020, Teatro Stabile di Torino worked with 63 theatre artists on seven radical, experimental digital theatre projects. The aim? To offer creative opportunities, while also putting artists “into a game they didn’t know how to play.”

One morning, I received the following email:

It is with great pleasure that we inform you that your application for Operation Omnia Munda Mundis (OMM) has been successfully accepted.

It is an honor for us to be the vehicle of your happiness AND mental cleansing, and we thank you for choosing us.

This was the beginning of “Open,” an immersive video game created for Argo. A group of 10 dramaturgs, directors and actors from the city had been brought together and given a keyword—“Open”—then set free to make a creative digital project over the course of a month. They made a game; another group, “Zero,” made a podcast.

They were joined by five other artist groups: “Elixir” (a manifesto), “Centimorgan” (a theatre map), “Parabasis” (a message to the nation), “Conjunctions” (an advertising campaign), and “Without a Body” (a social media narrative).

What did Teatro Stabile di Torino learn from curating these experiments? Lorenzo Barello, Head of the Development and Educational Office at the theatre, shared some thoughts with ETC.

Christy Romer, Communication Manager at ETC: Tell us a bit about the context behind Argo.

Lorenzo Barello: We started with a general reflection from the author Yuval Noah Harari: in the 21st Century, the main struggle will be about irrelevance. This usually refers to algorithms and so on, but we thought it could be a very strong sentence in the cultural profession—and it was confirmed by this real sense of irrelevance that we have all been experiencing since last Spring.

We are one of the seven national theatres in Italy—the biggest one, actually—and we usually work with 400 different artists and technicians during a regular season. This year that number was impossible to reach. At the end of 2020, we realized that we had the responsibility to give an important signal to the artistic community of our city. And so we decided to create a project that could help them.

It was hard to think about the best way to do so, because we couldn’t host everyone in our theatre, to perform or to do rehearsals, and we are also talking about quite a big community, made up of artists from different generations.

CR: What did the project look like in the end?

LB: We decided to work with 63 local theatre artists and 7 “editors.” Some were our usual actors, dramaturgs and directors, and some came from the city’s independent scene, who we hadn’t worked with before.

We divided these people into seven groups of 10 people. As they were different artists, from different generations, with different kinds of experience and a different kind of authority, we decided to put them on a field that was not theatrical. On stage, or a project that was stage-oriented, the older ones would probably have been too strong for the younger ones. It was an attempt at balance, and democratising the process. “Let’s put them into a game that they don’t know how to play” we thought, and move them towards a concept on which they have probably never focused their mind.

Another question was about collaboration. We were quite sure that each group was in need of an editor—someone that could help the groups make decisions, and give the right direction to their efforts. In the first few days, everyone was really happy to be part of the project, but they were really focused on their own things and talking about how things went during the previous months—the urgency, the needs. It took some days to find the right flow, and the editors were really helpful in that way.

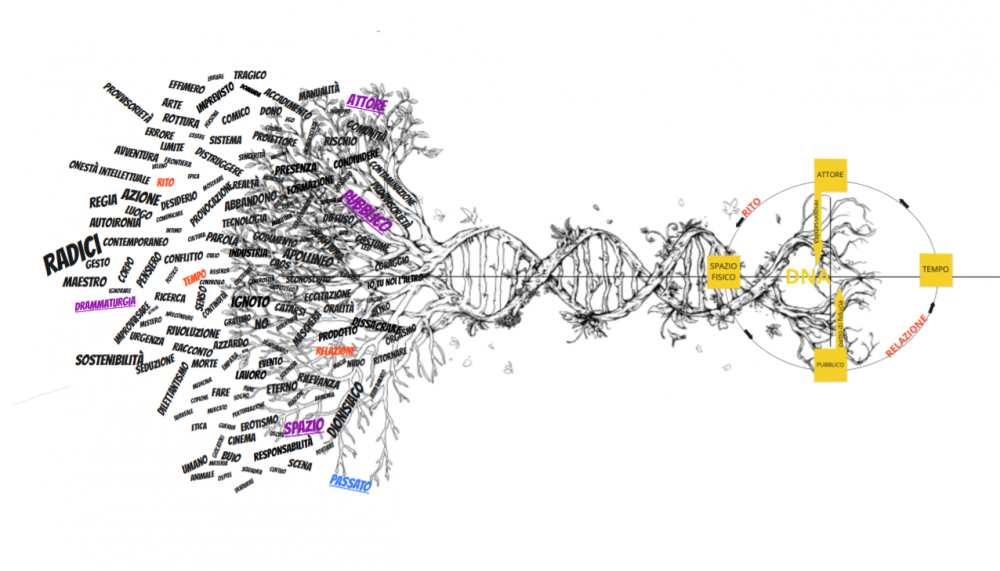

Centimorgan conceptual map (c) Teatro Stabile di Torino

CR: Yes. You could have had 63 artists doing 63 different things, which as a spectator or a process is perhaps less valuable. I can understand needing curation to reach a collaborative conclusion.

LB: Exactly. We worked in different ways with the various groups, because the people in them were different.

We gave each group a keyword, explained our choice briefly, and set out the result that we wanted to get from their work. For the first group, the word was Zero. They were free to choose: was it a countdown, or was it just the start of something? We asked them to produce a podcast, which they did, creating a five-act podcast. They wrote the story at home. We were quite happy about the work they did.

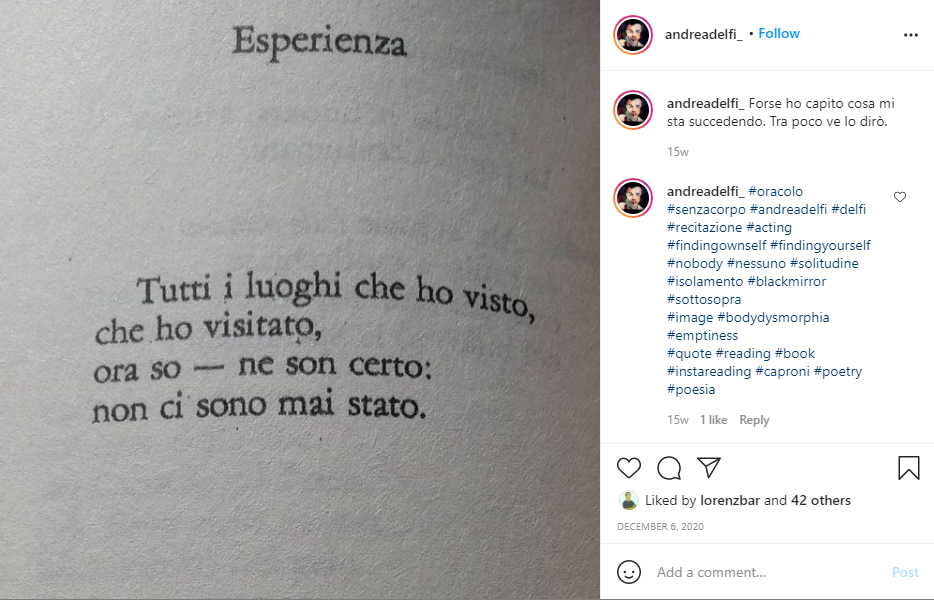

The second group received the word “centimorgan,” which is actually a measure used in genetics. We asked them to produce a mind-map of theatre in its widest sense. The third word was not a single word, but an expression: ‘Without a Body.’ We asked them to build a fake identity. They started to think about how we continuously tell a story about ourselves, and how we actually produce an identity for ourselves that we like—but that doesn’t always reflect what we are really like. They produced a fake identity for a man who lost his body and a story that you can read from the first post to the last one. The story is still continuing because the artists gave the passwords to a high school class that is now working and editing the fake identity.

Even though Argo was a completely digital project, and everyone was at home, connected to Zoom and working remotely, we thought that that project could be an opportunity to get to know each other and also to get in touch with the audience. That is something that usually doesn’t happen at our theatre.”

CR: Reading the description about digital identities being mixed up with real ones made me think about something I heard about people who have their Instagram hacked. They maybe have 200,000 or 300,000 followers and have to pay to get their account back. These people were interviewed and they say: I have to get my profile back! That’s my life! And it’s just an online thing, it’s not really their life… But at the same time it kind of is. Maybe it’s somehow more “real.”

LB: Yes. Some of the artists in the group didn’t have a social media profile, and it was strange to see the first contact of some artist, some director, with the social media world. It was quite surprising to see how the artistic community is aware and is not aware of the digital potentials that the web is giving us. I think that some of them discovered a completely new field of research and also a different possibility of being performative in an artistic sense.

Lorenzo Barello speaking at the ETC International Theatre Conference in Bratislava, 2018. (c) Peter Chvostek

CR: How much of the strategy of Argo was to reach younger people, or more digital natives?

LB: We didn’t design Argo as a possible way to reach new audiences. We designed Argo for the artistic community, as a way to give them work to do for a month, and to help them to discover new possibilities and also to get in touch with each other. From the beginning, we decided that audiences should be part of this project somehow. We worked with our usual audience and created seven audience groups, which were matched to the artistic groups.

The group which was working on fake identity, for instance, met the high school class. And then they give them the fake identity. The Elixir group, another group that was in charge of writing a manifesto, met a group of startups and young engineers working on robotics and digital technologies. and so on. The Zero group met 10 or 15 spectators over 65 and so on. Each group, at a certain point, worked together with the audience that was the strongest match. Of course at the end of the project the results we published on the web were mostly consulted and used by the youngest audiences, but that was only natural.

We realized that it is much more useful to be an open square than a castle on the rock. We usually are considered a castle on the rock—a big theatre, a huge budget, a lot of things to do, a lot of venues to manage and so on, very much concentrated on keeping the venue full of people to sell tickets, to help the big artists realize their projects.

CR: Why was it important to have this link up—for the artists to meet the audiences?

LB: Because even though Argo was a completely digital project, and everyone was at home, connected to Zoom and working remotely, we thought that that project could be an opportunity to get to know each other and also to get in touch with the audience. That is something that usually doesn’t happen at our theatre. So it was a good way, a very unique opportunity to put artists and audiences together and on a neutral field, which was not the stage.

At the very beginning, in the very first minute of those meetings, the balance was of course the oldest one: the audience was listening and the artists were talking. But at the end, in many of the groups, the balance was inverted, the audience was talking a lot, and the artists were listening and taking suggestions and so on.

CR: Did the audience have an influence on the outcome of the projects?

LB: The audience group that met the Zero group were the special fans of the Teatro Stabile, our closest spectators. They played the game for the very first time and gave a lot of suggestions to the group, and the group changed some things they’d planned.

CR:I had originally thought of Argo as a big digital project, because it happened online and used digital techniques. It sort of is, because it’s different to how you’ve done things before, but it kind of seems to instead be an experiment in democratising the creation of theatre, in making new spaces through which theatre artists can relate to each other, think about how they create, how they interact with audiences. It’s a bit like this idea that digital is not the antithesis of live—it’s just another tool, another mechanism for doing these things. Digital work is the tool we have now given the social context we find ourselves in.

LB: Yes, that’s what we tried to reach. And it was really the very first step because it was hard sometimes to reach the result. At the very end, we had to help the artists and give them technical help to reach what they had in mind, but I’m sure that the result of this experiment was quite good.

We decided to use digital technologies and the web for its peculiar language, and for the opportunity that it really gives—not only medium opportunities, but also creative opportunities. In recent months, many theatres decided to move what they were doing on stage onto the web. But that’s it—just a translation of a medium, and as it happens in every translation, something is missing. So that’s why we decided OK, let’s work on something that is born digital, or could be digital in a natural way—an advertisement campaign, a game, a mind map, and so on. These are digital objects, narrative objects made with digital technologies. Let’s try to work in that way. To use the talent of the artist, even if they are quite new to these digital fields. Let’s try to move them in this direction. Let’s take this terrible period of time as an opportunity to give them a way to discover other possibilities. That’s what we thought. With some of them I’m quite sure that we reached the results, and with some others no—I think they will run back to the stage when everything will end. But I am quite sure that some of the artists will try to work with the web or digital technologies in a new way.

It was just a very first step. We only worked for a month, and the results that we got were really surprising for a 30 day project, but I think that we could see some of the long term results in one year, something like this.

In recent months, many theatres decided to move what they were doing on stage onto the web. But that’s it—just a translation of a medium, and as it happens in every translation, something is missing. So that’s why we decided OK, let’s work on something that is born digital, or could be digital in a natural way.

CR: What about the impacts of Argo on Teatro Stabile? Has it changed or influenced your way of thinking, or how you will approach anything in the future?

LB: Well of course like everything that happens for the first time, it leads to a thought about the second time. So of course I think that this kind of community project should be kept in mind for our next programme. We realised that it is much more useful to be an open square than a castle on the rock. We usually are considered a castle on the rock—a big theatre, a huge budget, a lot of things to do, a lot of venues to manage and so on, very much concentrated on keeping the venue full of people to sell tickets, to help the big artists realise their projects. But this is just part of the game.

We understood that the artistic community around us is very important. The results…not really the results, but the feedback that we received from the artists, was really surprising. Very different from what we usually get from them. Everybody was really grateful, not only for the work opportunity, but really for the experience that they had during the project. In January we opened some rehearsals, just for a group of 20 people, per day, and we invited all the 70 people of Argo to come along. They met physically for the first time and it was a good moment. I don’t know, it was something maybe much nearer to a new friendship than a new colleague. With some of them, that was a feeling we had. We met someone that could be a friend, and not only a new colleague.

CR: I’m interested in the questions about where theatre fits in society. Lots of Argo was quite value-based, looking at the sort of world we want to create. Do you think theatre has not only a moral obligation to help the artist, but also to help shape the understanding of these difficult moments, and maybe help guide society towards such values?

LB: It’s a complex question, and the answer probably should be complex too. Of course we have to find a new balance. If the moral obligation that we have towards the artists, the theatrical sector is much more oriented to the way in which we were doing theatre before the pandemic, because the working system didn’t change. On the other hand, I think the pandemic shouldn’t be considered only a long parentheses or a long standby. We will probably be forced to change, and to reconsider the role of our institution inside society, because I think that our societies will need strong support from culture to find a new way and new balance after all this will be finished.

It’s a fact that time somehow was frozen by this situation and that we are stuck in a very long present tense. As soon as we are able to start to talk again about the future and having a long-term view, we will have to help our communities. I’m talking about spectators and artists, to find the right verbs to use in that sentence about the future. It’s going to be really hard, and the strongest effects and the economic effects are still to come, and so I think that we will have to make choices not only for the artists but also for lives. That will probably put ‘pure art’ a little bit apart for a while. I don’t know.

I think that [after the pandemic] we will have to ask more often what the audience needs, and what society needs, not only what we need, or what artists need.

CR: Maybe we will need to keep thinking about these things forever.

LB: I think that we will have to ask more often what the audience needs, and what society needs, not only what we need, or what artists need. And probably the answer to those questions will change our work and our action and our decisions. Many articles about welfare and culture…. I think even that connection should be rethought and redesigned a little bit, but we will have to face what things will be after all the pandemic. Theatre is a huge human machine—we’re not made of algorithms—so I can’t really make a concrete prediction for how things will be after… We have to use this moment to train ourselves through changement. To be ready.

This article was originally published by the European Theatre Convention and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Christy Romer.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.