Tokyo’s cozy 60-odd-seat Komaba Agora Theater isn’t perhaps where you would expect a cutting-edge multilingual drama experiment to be staged, but that’s just where Oriza Hirata has chosen to work his latest magic.

There, on a set made to look like a laboratory in the tropics, the playwright and director sweats over final preparations for the premiere of In the Heart of a Forest (Sono Mori no Oku), along with Japanese actors from his Seinendan company and others from the Korea National University of Arts in Seoul and students from the National Drama Centre of Limousin in Limoges, France.

Like the three previous plays in Hirata’s “science series,” which are set in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, France, and Japan, this one again presents a group of researchers, doctors, students, and business people intent, for different reasons, on identifying what differentiates apes, monkeys and humans.

However, this is the first time the 56-year-old dramatist has populated his laboratory with people from three countries speaking rapidly in their own languages but seeming to understand each other perfectly via hand-held translation devices. In reality, these fluid exchanges — conveyed to the audience through subtitles in Japanese — are actually not the result of technology, but of actors delivering their scripted lines with perfect, precisely synchronized timing.

Supposedly taking place in Madagascar, the play shows the multinational cast exchanging opinions while often exposing contentious differences between their own behavior or upbringing, such as differing views of history between Japan and South Korea.

“I have a bit of a scientific mentality, so I always want to push forward to find my limit,” the globe-trotting dramatist says. “That’s why I am now tackling the most complicated multilingual theater creation I’ve ever attempted.”

Hirata has staged works using more than one language several times before, and in 2010 he even created a trilingual (Japanese, Korean and Chinese) version of Tokyo Note, his award-winning take on social etiquette and the breakdown in human relations in a genteel museum.

“However, compared to Tokyo Note, which was structured around couples’ or groups’ unhurried conversations, the scientists’ debate is much faster and more complicated,” Hirata says. “And this time I’m trying to mix such different people and have them act seamlessly together.”

Hirata says that, while others have tried to tackle multilingual plays, “probably no one has ever written one from the beginning, though some have fashioned multilingual performances from existing works. So this is a satisfying challenge for me.

“I believe I’ve been able to emphasize the harmony possible in multicultural societies in a very natural way here. As a result, many people may feel strongly about it, although that’s a rare response with plays,” he says with a laugh.

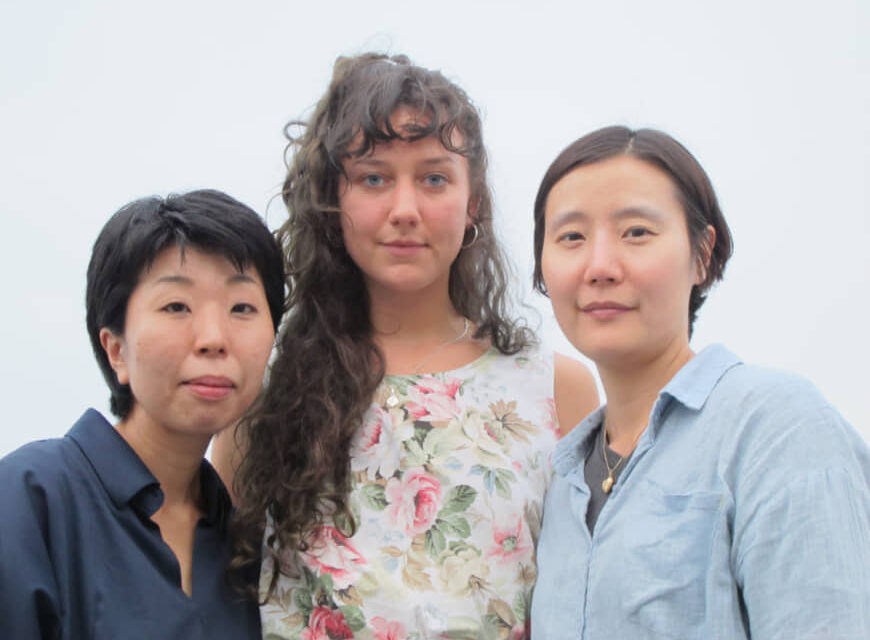

But how did Hirata’s ideals withstand the tense reality of rehearsals? I asked three actresses — Japan’s Izumi Sayama, Hyeyoung Kim from South Korea and Isabella Olechowski of France — who spent a month together with the rest of the cast at the new, purpose-built residential Kinosaki International Arts Center in Hyogo Prefecture.

Straight away, Kim and Olechowski say that Hirata’s meticulous direction was an entirely new experience for them.

“He insisted on absolute precision about, for instance, when actors entered or left, and he’d cue them to the second,” Olechowski says. “In France, we often act freely … and I never thought a single second could affect the outcome. However, I came to really understand how that could determine the play’s success or failure.”

“It looks like a very mechanical procedure, but such accuracy is key to keeping the harmony and natural flow of Hirata’s work,” Kim says. “But mainly, from my experience here, I’ve learned the importance of all the actors working for each other.”

Meanwhile, Sayama — who is well-versed in Hirata’s direction — drew on her experience working in South Korea on 2013’s award-winning collaborative production of Karumegi (The Seagull) by Tokyo Deathlock and 12th Tongue Theatre from Seoul.

“Foreign actors inevitably rely on the interpreter a lot, so it can take much more time and effort than a regular domestic production,” Sayama says. “However, I learned that it’s still better to wait until everyone shares the same understanding and is being respectful of the other’s background.”

It’s Hirata’s approach, she says, that allows audiences to witness a kind of theater they’d probably never seen before.

“That alone is reason enough to see this unique performance,” Sayama says. “I personally like the opening scene in which actors come and go rapidly like on a linguistic scramble crosswalk — but somehow audiences can enjoy that chaos, too.”

Aside from their professional interactions, though, it was clear the cast also had lots of memorable personal exchanges during that working sojourn in Kinosaki.

“I loved going to one of the many hot springs every day and often wandered around with Sayama-san,” Kim says. “I also saw how the French people (with us) enjoyed sunbathing after lunch, so I tried it and found what a great relaxing pleasure it was — even without sunblock! I also studied their culture, especially how they concentrated intently during rehearsal until they had a break — then they enjoyed that 100 percent.”

“This play is a part of our graduation work and will be presented next spring in France,” Olechowski says. “So we’ve been looking forward to coming to Japan for two years since Hirata told us about it when he came to Limoges to do his workshop — but many things were still a culture shock for me.

“However, I believe theater is born from new encounters with new people and things, so this is the perfect graduation project for us.”

Amplifying that view, Hirata says, “Ways of showing motivation differ between nationalities, but each actor needs to trust the others and believe everyone is there to create the best play together.”

In contrast, in the play itself, scientists and experts argue over the difference between various primates, with each trying to tailor the study for their own academic kudos or business benefit.

Then in the final scene, overarching good sense comes from a female scientist with an autistic son. To say more, though, would be a serious spoiler — whether in Japanese, Korean, French … or English.

This article originally appeared in The Japan Times and has been reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Nobuko Tanaka.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.