Adelaide di Borgogna highlights the beauty of its music and the very good cast

The Plaza Vaticano in Buenos Aires is the incongruous name given to the square between the Colón Theatre and Viamonte street. A large space, it can hold more than five hundred seated people. Last year, the Plaza Vaticano held its second Music Festival, and recently a varied program could be seen in its third Festival from January 14 to February 5. Considering that January is a desert as far as live music in roofed and walled venues goes, this festival makes sense, and that’s why I commented some of the events last year.

Pros: a) in two cases you could see/hear important Colón programs: Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess opened the Festival, and last Sunday Argerich and Barenboim played together (featuring Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring). b) You can appreciate operas from Aix-en-Provence, Pesaro and Venice, ballets from Sweden and Montecarlo (and an equestrian ballet from Salzburg!), concerts from Finland’s Savonlinna and Helsinki, and Berlin. c) It’s free, first come first served. You may disagree with certain choices but surely some of them are worthwhile. d) The projections in ample screen and the sound (not too loud) are of good quality.

Cons: a) Live music in good acoustics is always far better. (If you think that the Colón Theater should be used, fact is that the whole staff is on vacation during winter). b) Noises are an unavoidable nuisance: babies crying, dogs barking, children yapping, buses roaring by, sirens, even the trash truck in full cry… and members of the audience somehow believing that because it’s open air they can talk whilst they listen! c) Possible electricity cuts. d) Bad weather leading to cancellation. e) Total lack of information in paper; a flyer is cheap and should be provided.

Jorge Agote, Director of the Festival, says: “In the name of the Asociación Civil Cultural Centro Histórico Teatro Colón, we welcome you to the Festival, and thank the Alliance Française, the Embassies of France, Finland, Austria and Italy, the Instituto Italiano de Cultura, Arpeggio, the Colón, the Grupo Petersen, Grupo IMR and Grupo Relats.”

My first choice was Adelaide di Borgogna, opera seria by Gioachino Rossini (new spelling: it used to be “Gioacchino” and I prefer it). It had the guarantee of being a production of the Pesaro Rossini Opera Festival; that city was his birthplace and a natural to re-evaluate forgotten works of the great composer, aided by critical editions prepared by specialists. I’m not sure whether this particular opera was premièred here in the Nineteenth Century, but it certainly wasn’t staged in the Twentieth and Twenty-First. And at least in my 2000 catalogue of CDs, there’s no recording save for two fragments.

Many aren’t aware that Rossini wrote more opere serie than opere buffe, and obviously, his three hits are The Barber of Seville, The Italian Girl in Algiers, and Cinderella. And it’s true that they are marvelous. The “serious” ones tend to be overlong and often lack some degree of dramatic intensity; also, there’s an excess of roulades. But even so, there’s a lot to admire in them and our city should get to know more of them. During the last sixty years, I can only recall the following: Guglielmo Tell, Elisabetta Regina d’Inghilterra, and Ermione. We need at least Semiramide, Moïse, Le Siège de Corinthe, Otello, and La donna del lago.

I can’t say that I found Adelaide di Borgogna quite at that level, but it gave me much pleasure, both for the beauty of its music and the very good cast and conducting. It was written in 1817 at 25, a year in which he also composed Cenerentola (Cinderella), La gazza ladra and Armida. The librettist of Adelaide was Giovanni Schmidt, who had also written Elisabetta and Armida.

Time for some background, for we are deep in Medieval times and the protagonists were crucial in Italian history. Bear in mind that this opera is also called Ottone, Re d’Italia. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, “toward the middle of the 10th Century, the Kingdom of Italy was torn by the struggles among the great feudal lords. Upon the death of Lothar II, Berengar II of Ivrea, who, with his son, Adalbert, already held virtual power, was crowned king. But an opposition headed by a courageous woman, Adelaid, daughter of Rudolph of Burgundy and widow of Lothar, called for help from Otto I of Germany. Otto came to Italy in 951, donned the royal crown in Pavia and married Adelaide. Soon after, Berengar and Adalbert regained rule over Italy, though, as vassals of the German king. Otto returned in 962 and was crowned in Rome together with Adelaide.”

With some melodramatic adaptations, such is the story of the opera, naturally stressing both Otto’s and Adelaide’s rights and the villainy of Berengar (Adalbert is his father’s puppet, in love with Adelaide and refused). And recounting the various vicissitudes of war, in particular, the battle of Canossa (a fort and city), and the times in which Adelaide was a prisoner.

In this case, the Festival had recourse to the Chorus and Orchestra of Bologna’s Teatro Comunale, institution of considerable standing and long tradition, and the conductor was the talented Dimitri Jurowski. There’s a lot of choral work by soldiers and courtiers of both sides, done in this performance with good voices, accuracy, and conviction. Jurowski proves to be a connoisseur of the Rossinian style and gets very clean playing from the Bolognesi. The edition is signed by Alberto Zedda and Gabriele Gravagna and certainly sounds authentic, though some pruning of excessive flowery writing would have been welcome (that’s the problem with zealous historicists); at least this opera in two acts lasts two hours and a half, an hour less than Semiramide (admirable but heavy) and doesn’t outstay its welcome.

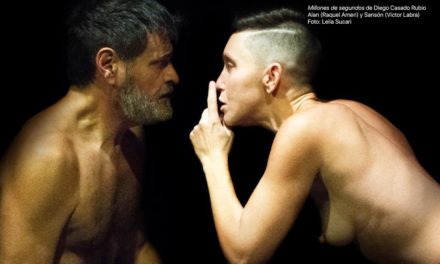

A curious and admittedly rather absurd decision of the composer (probably because he had the right singer) was to write Otto’s part for a contralto; he did a similar thing with the warrior Arsace in Semiramide. Marilyn Horne showed in that role that (along with Sutherland in the soprano Queen) she could give us wonderful bel canto, and they were a huge success both at the Met and La Scala. Less starry but certainly redoubtable are: as Adelaide Daniela Barcellona and Jessica Pratt, the latter a new name for me and a revelation: the contralto has a hefty physique and the soprano is an attractive woman, but both give dramatic substance and powerful musicianship to their difficult tasks.

The men also showed their mettle. At the Colón we knew Nicola Ulivieri as a valuable Giovanni; here his strong voice and acting give character to Berengario. And Bogdan Mihai is an expressive Adalbert bringing fine tenor singing to his frustrated suitor. Lesser parts are well taken.

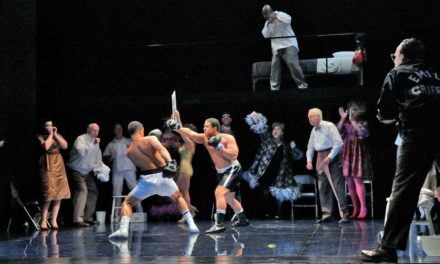

Pier’Alli is the integral author of the show: director, stage, costume, and lighting designer. I found it interesting: he evokes Mediaeval times and battles with a mixture of projections, painted drops, colorful solid elements, etc., and moves the singers coherently. He uses modern techniques but stays faithful to the times of Adelaide.

This review was originally published in the Buenos Aires Herald. Reposted with permission. Read an original article here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Pablo Bardin.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.